The 20th Party Congress showed Xi Jinping doubling down on existing policy initiatives with little sign of major adjustments, but economic and structural developments will put growing pressure on Xi to deliver on his reform agenda

The 20th Party Congress might well go down as one of the most significant in recent Chinese history. The reason for this is less due to Xi Jinping staying on for a third term, and more to do with the glaring discrepancy between the message that the leadership wanted to convey and the one which was perceived by audiences both domestically and globally.

Xi wanted to stress stability but to many, there appeared to be a reinforced sense of uncertainty, not least because of his explicit support for China’s highly disruptive zero-Covid policy. Xi also wanted to show continuity, but again, there was a perception of disruption, especially regarding his predecessor Hu Jintao, who – in one of the most extraordinary moments of the Congress – was be removed from the stage for reasons still not fully explained. Finally, by surrounding himself with apparently unremarkable allies and long-term collaborators, Xi raised doubts about the prospects of much-needed reforms – many of them promised for years but yet to be delivered.

But all is not quite doom and gloom. Xi’s opening speech – a sort of CCP manifesto for the next five years – was, to an extent, anti-climactic. It included little that had not been said before, belying the alarmist headlines in many Western media. Li Qiang – although somewhat tarnished by the chaotic Shanghai lockdown earlier this year – is expected to be the new Premier and has a generally business-friendly reputation; he is expected to continue his predecessor’s policies of supply-side reforms and trade liberalisation.

Furthermore, the promotion of former Minister for Environmental Protection Chen Jining – an Imperial College graduate who spent ten years in the UK – to Party Secretary of Shanghai, means that Xi’s ambitious Net Zero goals and green development agenda is now a key performance indicator for Party officials eager to climb the career ladder. Regarding foreign policy, the appointment of the current Chinese Ambassador to the United States Qin Gang to the Party’s Central Committee (CC) – suggesting that he will be promoted to Foreign Minister at the next Two Meetings (Lianghui) in March 2023 – also indicates a willingness to manage US-China relations more closely. It is worth remembering that current Foreign Minister Wang Yi – a Japanologist – entered office at the height of the conflict over the Diaoyu islands and subsequently managed to put the bilateral relationship between the two neighbours on a more stable footing. Qin’s appointment could therefore be seen as a sign that Beijing is clearly worried about the friction between the two superpowers and wants to defuse tensions before it’s too late.

Finally, the removal of former Xinjiang Party Secretary Chen Quanguo – who was responsible for the alleged internment of up to a million Uyghurs – from the Central Committee, despite him not having reached retirement age, should equally be seen as a positive signal, confirming recent reports that Beijing is looking for an end to the controversial policy.

Nonetheless, Xi’s unquestionable success at consolidating power at the head of the CCP will put increased pressure on him to make good on his promises to wean the Chinese economy from its reliance on unsustainable infrastructure spending and enact the reforms needed to increase domestic consumption. And if the Hu Jintao episode proved one thing, then time might not be on Xi’s side.

Background

Policies

On 16 October 2022, Xi opened the 20th Party Congress with a nearly two-hour-long speech, outlining the Communist Party’s ‘manifesto’ for the next five-year cycle. A much longer version was published later, containing more policy details and theoretical musings on Marxism with Chinese Characteristics. Yet both Xi’s oral version and the longer written one included little which had not been mentioned elsewhere before.

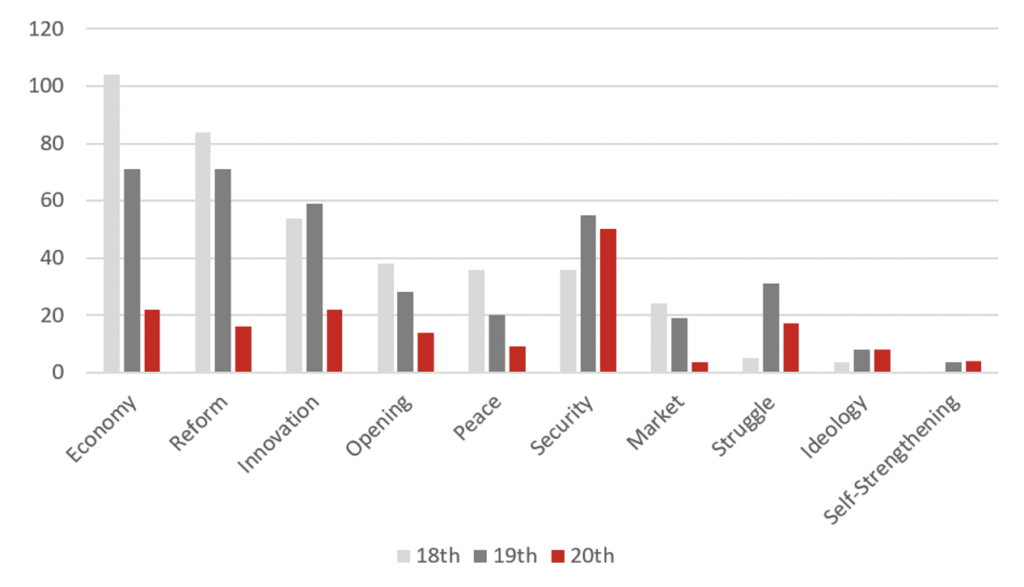

Mentions of keywords in the Party Congress reports in 2012, 2017 and 2020

Analysts of Chinese Party-speak were quick to point out that this year, the number of mentions of the term security (安全) overtook mentions of the ‘economy’ (经济) compared to the two previous congresses in 2017 and 2012, leading to the conclusion by some that for Xi, the economy is no longer the government’s top priority.

And indeed, references to economic policy were mostly summed up under the newish term of ‘new pattern of development’, which refers to such concepts as the dual circulation strategy (i.e., removal of local trade barriers and balanced trade), self-reliance in key technologies, green development, and common prosperity. Commitments to reform and opening-up, trade liberalisation and openness to foreign investment were duly repeated.

On common prosperity, Xi started by noting that income distribution – meaning policies reducing income inequality both regionally and between income groups – is the ‘foundational system’ of the policy. But he also emphasised that job creation remains the principal tool to achieve this goal, underscoring Xi’s general distrust towards a Western-style welfare state.

More specifically, Xi said that China needs to establish a policy system to boost birth rates and bring down the costs of pregnancy and childbirth, child rearing, and schooling. This is in line with last year’s decision to ban private online tutoring but could also herald a much more intrusive approach towards family planning, perhaps even a total ban on abortions or policies penalising singles compared to families with children.

Most ominously, Xi announced that there would be more corruption crackdowns, indicating that the Party’s watchdog – now headed by Li Xi – would focus especially on ‘sectors with a high concentration of power, funds, and resources’. And while Xi did not specify what sectors he had in mind, the recent crackdown on public fund managers involved in China’s rapidly increasing semiconductor industry as well as the post-congress suspension of PBoC vice-governor Fan Yifei provide some powerful clues to the potential targets.

People

Although any report by Xi attracts widespread media attention, the 20th Party Congress was not primarily about him, rather, it was about the people joining him at the apex of the Party.

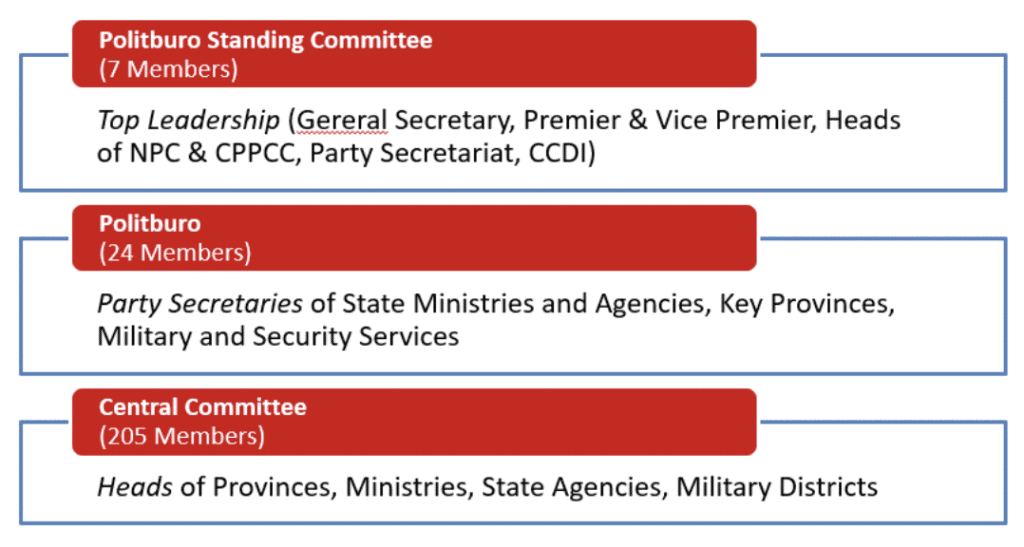

The top leadership of the CCP is a pyramidal structure consisting of the Central Committee (CC), the Politburo (PB) and the Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC). Each member of the PBSC must be a member of the PB, and all have to be part of the CC. To use a slightly imperfect analogy with the British parliamentary system, the PBSC represents the front bench of the CCP, while the PB and the CC are the cabinet and the backbenchers, respectively.

Leadership structure of the CCP after the 20th Party Congress

Unsurprisingly, the PBSC attracts most of the attention as it constitutes the Party’s top leadership organ and makes the key decisions on strategies, major policies and personnel changes at the national and provincial level. In short, the PBSC is the CCP’s (and thus China’s) board of executives.

As such, the 20th PBSC is now almost exclusively packed by people with whom Xi has worked at various stages of his career. Only Zhao Leji and Wang Huning stayed on from the previous term. Zhao, who took over from Wang in the internal hierarchy, is now responsible for the National People’s Congress and thus decides which laws and regulations get passed by the country’s legislative body. Zhao also remains the only PBSC member whose career started in the Party’s youth organisation, the Communist Youth League. Wang, who was previously in charge of the Party’s secretariat, is now overseeing the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), which, among other things, manages the so-called ‘United Front’, including its relationship with Chinese organisations abroad.

Of the four new entrants, all have worked with Xi previously:

- Cai Qi has shared the longest common trajectory, working with Xi during his time in Fujian (1988-2002)

- Li Qiang was Xi’s deputy in Zhejiang

- Ding Xuexiang became his secretary in Shanghai, before following Xi to Beijing in 2013

- Li Xi was Party Secretary of Yan’an, the CCP’s stronghold during the civil war period and the place where Xi spent his time during the Cultural Revolution. Li was subsequently promoted to Party Secretary posts in the key provinces of Liaoning and Guangdong.

Other key appointees share a similar background. He Lifeng, the new economic policy czar and successor of Liu He, started his career under Xi in Fujian province, while Li Shulei, the new head of China’s important propaganda ministry, was working at the Central Party School at the same time Xi was heading the institution between 2007 and 2012.

CBBC Outlook

A curious feature of Xi’s preference for known faces is that nearly all of them hail from China’s prosperous and entrepreneurial coastal areas. Li Qiang is probably the most characteristic representative of the pro-business Party official, heading Wenzhou – a poster child of China’s private sector – in the early 2000s. He also served as Party sponsor for Alibaba’s Jack Ma and convinced Tesla to build its first gigafactory outside the US in Shanghai.

Yet despite this background, businesses will expect more than just warm words of support from the new leadership. Many of the reforms outlined by Xi at the onset of the Congress have been on the agenda for years. And even though there has been some progress on legal institutionalisation and poverty alleviation, critical reforms, such as better access for private businesses to sustainable financing, the removal of local trade barriers, and stable public finances of local governments currently hooked on property sales and infrastructure investments, are yet to make visible headways.

And while Beijing has promulgated one concept after another, be it the dual circulation strategy (to eliminate local protectionism), a national social credit system (to enable a nationwide exchange of personal and company information) or common prosperity (to reduce social equality), Beijing’s structural penchant for delegating policy implementation to local governments has often meant that it was tasking the fox with guarding the henhouse, thus limiting the very effectiveness of its reform initiatives.

Whether Xi’s handpicked new team can take a more forceful approach and overcome local resistance remains to be seen, and we will probably have to wait until the next Two Sessions in March 2023 to get a better idea of his reform agenda. But the fact that Xi defied the convention of his two predecessors, who chose to step down after two terms, also means that pressure on him to deliver results or to designate a successor could grow rapidly. And given that China will have to exit zero covid before anything can move ahead, he will have to hurry.