China’s government has long had a penchant for announcing grand policy initiatives with titles that can appear somewhat unclear – think of Jiang Zemin’s ‘Three Represents’, or Hu Jintao’s ‘Scientific Development’. The latest in this tradition is Beijing’s catchily titled new economic framework, the so-called ‘Dual Circulation Strategy’ (DCS). Since it was first mooted in May 2020, the DCS has attracted much scrutiny, both within and outside China. CBBC’s Torsten Weller explains what it might mean for China’s economic development.

As is often the case in China, the DCS strategy contains many continuities with past policy: its core objective is for China to continue with its long-desired transition away from an export and investment-driven growth model and towards one more driven by domestic consumer spending.

Where the DCS moves things on is in its emphasis on reducing China’s reliance on foreign inputs in areas like technology, and in its expressed desire to rebalance China’s trading relationships.

The DCS’s aims for China to have a strong manufacturing sector and a high-value consumer market are achievable in theory. The main challenge for policymakers will be to put this into practice if local wages remain far below those in other developed countries.

Its core objective is for China to continue with its long-desired transition away from an export and investment-driven growth model towards one more driven by domestic consumer spending.

Background

Though Chinese policymakers first used the ‘dual circulation’ term at a Politburo meeting in May, it wasn’t until late July that Qiushi – a Communist Party journal that serves as the principal interpreter of government-speak – offered a more detailed explanation.

In a short editorial, Qiushi wrote that the main idea of ‘dual circulation’ is to strengthen China’s vast domestic market (‘internal circulation’), while shifting its foreign trade (‘external circulation’) to suit the needs of Chinese customers more closely – rather than those of overseas buyers, as is typical for an export-led growth model.

According to Qiushi, the strategy revolves around three main objectives:

1) Technological innovation: China needs to accelerate its research into advanced technologies and become a pioneer in areas such as AI, quantum computing, and the use of blockchain ledgers for administrative services.

2) Industrial upgrade and increased consumption: This involves the use of more efficient production processes in manufacturing, leading to higher incomes for Chinese workers who will then have greater spending power.

3) Free flow of factors of production: Further reforms are needed in areas such as the transfer of land rights, movement of labour (i.e. hukou reform), and the transfer of intellectual property and data.

A new push for self-reliance…

The Qiushi piece largely appeared to rehash some of China’s already well-known policy goals. Yet Jude Blanchette and Andrew Polk, two prominent China analysts at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), argue that despite its vagueness, the DCS could turn out to be as consequential as China’s recent supply side structural reform, which has led to significant consolidation of the country’s state-owned enterprises and stricter regulation of its once rampant shadow banking sector.

Blanchette and Polk see the increasingly uncertain global economic outlook as the principal driver behind the DCS. They suggest its main objective is to reduce China’s reliance on foreign demand and inputs in critical areas such as energy, technology and food.

Both analysts expect that the DCS will lead to an ever greater focus on China’s ambitious industrial policy, epitomised by the Made in China 2025 and China Standards 2035 initiatives. Both are aimed at boosting China’s advanced manufacturing base to create world-class champions capable of competing with German and Japanese producers.

They also warn that this emphasis on moving up the manufacturing value chain could come at the expense of the development of China’s services sector, which had been receiving more attention in recent years.

…or the final stage of economic development?

Cheng Shi, chief economist at the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), has provided an alternative view to Blanchette’s and Polk’s ‘either-or’ reading of DCS. For Cheng, the DCS seeks both to improve China’s manufacturing capacity, and to increase its trade in services. He sees the strategy as the logical next step in China’s economic development, following the path of other industrialised nations, especially that of the U.S. at the turn of the 20th century.

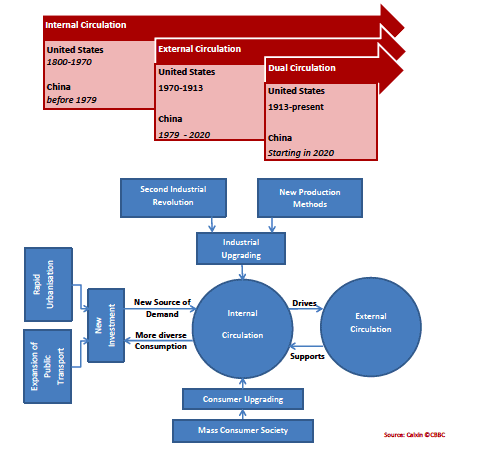

Cheng lays out a three-stage model of economic development, with China now roughly at the beginning of the third level. In the first stage, an economy is backward and relies on agriculture and raw material exports, while advanced products have to be imported from abroad. In this phase, the domestic market – or ‘international circulation’ – is underdeveloped and depends heavily on foreign demand and inputs. The combination of low-value exports with high-value imports leads to the country running a wide trade deficit.

For Chen, this first stage corresponds roughly to the period between 1800 and 1870 for the US; for China, it relates to the period before the beginning of the reform and opening-up period in 1979.

The second stage (which in the US corresponds to the period from 1870 until the eve of World War I and in China to the four decades between 1979 and 2020) is the age of industrial revolution. During this era, an economy usually goes through a rapid increase in the production of cheap consumer goods, which are mostly sold to foreign markets. The country’s trade balance moves into surplus with external markets driving demand.

In the final stage of development, domestic wages catch up with those in developed countries and consumers have enough money to drive demand for products and services from both domestic and international businesses.

The principal characteristics of this period are a relative decline in demand for basic goods such as food and clothing in overall consumption, with a concomitant relative increase in spending on entertainment, travel, and housing.

While this stronger demand usually leads the country’s trade balance into deficit, the strength of the country’s ‘inner circulation’ begins to reshape the global system, through an increase in its outbound foreign investment and the growth of its trade in services. The country thus completes its transition from having a poor and passive economy dependent on foreign capital and demand, to one that is an active shaper of international trade flows.

According to Cheng, the US reached this last stage at the onset of World War I, whereas China is just about to enter into it. The principal characteristics of this period are a relative decline in demand for basic goods such as food and clothing in overall consumption, with a concomitant relative increase in spending on entertainment, travel, and housing.

In the US, this epoch was exemplified by the ‘Coolidge boom’ of the early 1920s, when new industrial production methods like Ford’s assembly lines, combined with a previous upsurge in railway building and urbanisation, led to widespread prosperity and the emergence of a genuine consumer society.

Cheng argues that the application of new technologies, such as automation, AI, and 5G – allied to the benefits of China’s modern transport network and continuing urbanisation – could bring about a similar boom in China, making it not only less dependent on the vicissitudes of the global economy but also leading to a fairer income distribution at home.

Cheng’s Three-Stage-Development Model of ‘Dual Circulation’:

Old wine in new bottles?

To many seasoned observers of Chinese politics, the ‘dual circulation strategy’ appears merely to be a rebranding of China’s well-known push for a transition away from export and investment-driven growth towards a more sustainable consumer-driven model. It especially resembles Xi’s famous ‘New Normal’ speech in 2014, when he called for an upgrading of China’s labour-intensive manufacturing sector and a fairer distribution of income between the country’s rich urban areas in the east and its poorer rural regions in the western hinterland.

Oxford-trained economist Yu Yongding pointed out in a recent speech that the concept of dual circulation can be traced back to the late 1980s when it was first proposed by the economist Wang Jian in internal policy discussions.

Moreover, the core concept of the DCS, namely that domestic consumption should become the key driver of economic growth, was in China’s 11th Five-Year Plan back in 2006. Yu blames a lack of political will for the failure to implement this strategy earlier and considers it long overdue.

Michael Pettis, co-author of the recent book Trade Wars are Class Wars and an economics professor at Peking University, has argued that two major problems stand in the way of successful implementation of the DCS.

Firstly, a successful rebalancing of China’s economy towards domestic demand will require a considerable transfer of wealth from firms and investors towards ordinary households, either via either higher wages or a far more robust social welfare system. Pettis questions whether the political will truly exist to bring this about.

Pettis argues that even if China achieves higher wages, the consequent increase in labour costs would undermine the international competitiveness of Chinese exporters

Secondly, Pettis argues that even if China achieves higher wages, the consequent increase in labour costs would undermine the international competitiveness of Chinese exporters. These higher wages would not only weaken Chinese manufacturers’ position vis-à-vis foreign competitors, but would also increase the country’s dependence on the global financial system – as China would need to borrow more from global markets to fund its consequent current account deficit.

Is this time different?

Despite the sense of déjà vu surrounding the DCS, there are several good reasons to believe that this time could be different.

Cheng Shi’s argument that technological transformation, urbanisation, and rapid extension of transport networks can generate strong growth is sound. And although his analogy with America’s ‘Roaring Twenties’ is somewhat awkward, the US’s experience in the first half of the 20th century does suggest that countries can simultaneously achieve the twin goals of strong manufacturing development and more robust consumer spending.

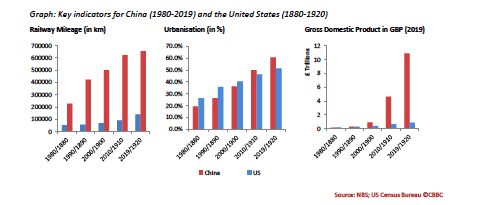

In fact, over the last four decades, China has undergone a similar transformation to the US in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For example, according to official statistics, China’s urbanisation rate surpassed 60% in 2019, higher than the US’s 51.4% rate in 1920.

In terms of overall economic growth, China has massively outperformed the turn-of-the-century US The Chinese economy increased more than seventy-fold in size between 1980 and 2019; by contrast, the American economy only quadrupled in size between 1880 and 1920. Nonetheless, it grew by a further 30% in the following decade, building on the foundation of growing cities and a more developed transport network.

China’s economy could well continue to expand at a similar rate. As Tom Orlik pointed out in his recent book China: The Bubble that Never Pops, China’s ‘build-it-and-they-will-come’ approach has proved more than one doomsayer wrong in the past.

CBBC view

The ‘dual circulation strategy’ does not present a fundamental change in China’s economic policy approach. But it does add the goal of a more balanced trade relationship to the long-held ambition to shift the country’s economy to a more consumer-driven model. It also highlights fundamental structural changes that have taken place in China which, taken together, provide a firm basis for further economic growth in the coming decade.

Lessons from developed countries do indeed point towards the considerable benefits of urbanisation and better transport networks for economic growth, and we expect continuing spill-over effects and new emerging consumer markets in China’s smaller cities.

But whether the continuing growth of China’s domestic demand will lead to a fundamental rebalancing of China’s trade patterns remains questionable. As the case of Germany shows, and as Klein and Pettis have correctly pointed out, building a strong manufacturing base and having balanced trade are two different things. While China might implement the former, it will probably struggle to achieve the latter.