Chinese tax authorities have vowed to crack down on tax evasion by celebrities and online influencers such as Fan Bingbing and Viya, but they’re also keen to reduce taxes and fees for businesses and SMEs, writes Torsten Weller

One of the most visible expressions of China’s new ‘Common Prosperity’ policy has been the stricter enforcement of individual income tax violations. In December 2021, Chinese tax authorities fined live-streamer Huang Wei – also known as Viya – the record sum of RMB 1.34 billion (around £186 million) for non-payment of individual income tax (IIT). This is the largest fine since Fang Bingbing, a movie star, was ordered to pay around £100 million for the same offence in 2018.

At a meeting earlier this month, Wang Jun, the head of the Chinese state tax administration (SAT) vowed to “punish severely all kinds of tax evasion and show no forgiveness.” Somewhat contradictorily, Chinese authorities also said in December that they would show leniency to live streamers who settled their outstanding tax payments voluntarily before the end of 2021. Wang even announced that SAT would implement a policy to exempt first-time offences. At the central government level, the message about IIT is equally equivocal.

At the Central Economic Work Conference in December, Chinese leaders repeated their promises to further reduce taxes and other fees. In total, the financial burden on businesses will be reduced by RMB 1.1 trillion (£139 billion) in 2022, following a similar reduction the previous year. The government also announced that it would maintain tax benefits for ‘talents’ and highly educated employees. Beijing even extended – at the last minute – a tax exemption on fringe benefits for expats.

While China’s stoic adherence to supply-side policies might be good news for companies and foreign employees, the tightening control and increasing use of big data by Chinese tax authorities also requires a far more circumspect approach to Chinese operations.

Background

China’s tax system for individual incomes has undergone several important reforms over the last couple of years. Most of the changes have been aimed at improving tax compliance and the SAT’s own efficiency. China’s fapiao reform in 2017 – following the introduction of a nationwide VAT a year earlier – targeted widespread tax fraud which relied on false invoices (called fapiao) to skirt IIT obligations.

Tax authorities also expanded their online tax platform – the ‘Golden Tax System’. Initially designed to process VAT invoices, the system has expanded over the last couple of years, including ever more data. Importantly, it has also served as a tool to integrate tax files from different tax offices. Previously, each tax bureau had its own independent reporting system, requiring companies to de- and re-register their tax records if they wanted to move offices from one district to another. The latest expansion – called ‘Golden Tax IV’ – which will go online this year, not only increases tax sharing capabilities between local and state levels, but also monitors non-tax contributions, such as social insurance fees.

The new system thus incorporates the 2018 reform which expanded the SAT’s remit to include not only taxes but social insurance fee collection as well. Previously, these fees – including healthcare, pension, unemployment, sick pay, and maternity pay, plus a contribution to the local housing fund – were overseen by a separate social insurance administration. Unsurprisingly, the lack of data exchange between tax and social insurance authorities made it easy for employers to game the system by underreporting income, thus dodging both contributions and taxes.

It is against the background of these reforms that the recent crackdown on film and online celebrities is taking place. Better access to tax and social insurance data has allowed Chinese tax authorities to collect revenues more efficiently.

The new online system also allows tax officers to absorb more information. In the case of live streamers, this has had a significant impact. As Caixin, the Chinese business weekly, pointed out, many artists and social media influences (Key Opinion Leaders or KOLs) have set up sole proprietorship enterprises or partnership enterprises.

Unlike larger companies or wholly foreign-owned enterprises (WFOEs), they do not pay corporate income tax (CIT), but only individual income tax plus social insurance fees. But because of the lack of proper accounting, tax authorities often charged taxes based on estimates rather than bank statements, receipts or transaction records. This appears to have made it possible for live streamers to hide a considerable chunk of their income and lower their effective tax rate from a maximum rate of 45% to often less than 10%, according to Caixin.

That approach changed this year, with tax bureaus now demanding the same financial documentation as from other companies. Additionally, greater access to data also allows authorities to compare transactions across the entire sector and thus get a better idea of the actual amount of money paid to live streamers and other celebrities.

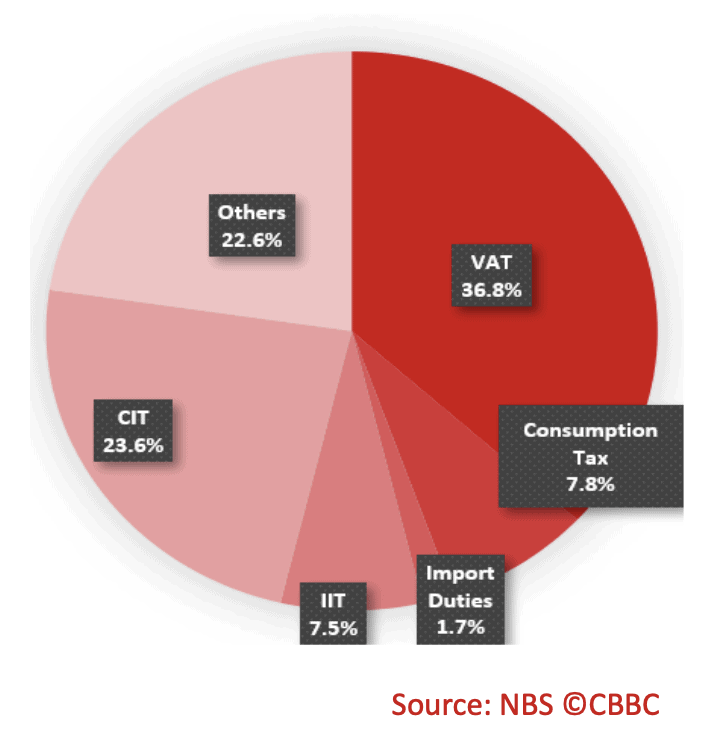

Tax income distribution in 2020

China’s lopsided income tax distribution

The improved tax compliance of high-net-worth individuals is certainly a positive development. But whether it is enough to help cash-strapped provinces and local authorities to improve social services remains to be seen, not least because individual income tax is only of minor importance for the Chinese government’s budget. In 2020, IIT accounted for only 7.5% of the government’s tax revenue, compared to 24.2% in the UK and 23.5% among OECD countries. The majority comes from the VAT and corporate income tax (CIT), which together accounted for 60.4% last year.

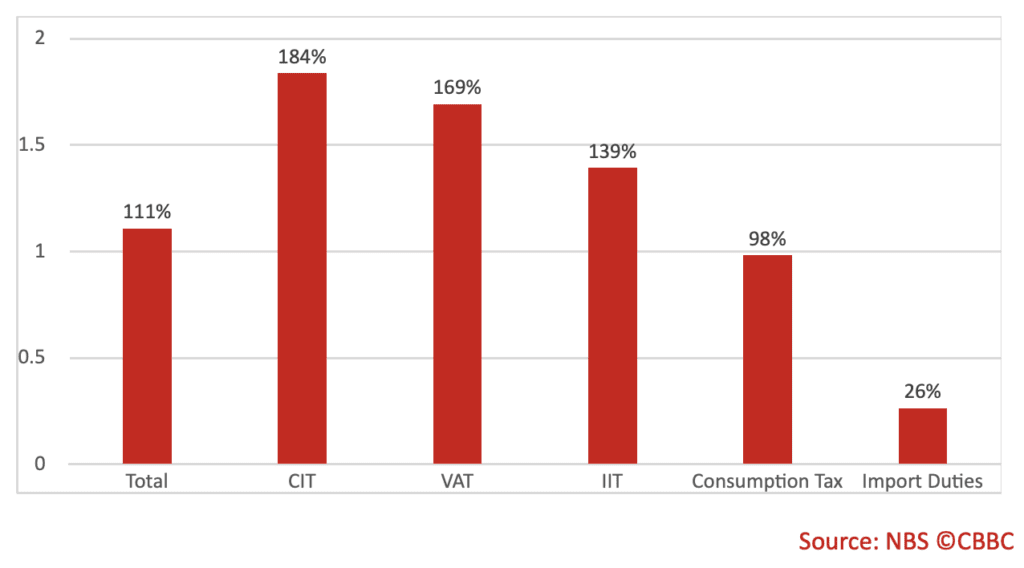

Nonetheless, Chinese official statistics suggest that the individual tax burden has increased over the last ten years, especially for high-income earners. Tax income from IIT increased by 169% between 2010 and 2020, compared to a total growth of 111% for all government revenue. More importantly, disposable income derived from wages and salaries only grew 145% in the same period. If we further consider the monthly tax-allowance of RMB 5,000 (60,000 RMB/year), and that only a fifth of Chinese households recorded an annual income above that threshold, then it becomes clear that a tiny fraction of China’s working-age population has carried the brunt of the government’s growing IIT revenue.

This lopsided tax burden explains the government’s conflicting messaging on tax cuts and stricter enforcement. It also points at one of the core challenges for Xi Jinping’s new ‘Common Prosperity’ policy: how to convince China’s growing middle class to spend and invest more while also increasing government revenue to meet the growing demand for better education and social services.

Increase in tax income between 2010 and 2020

Integration instead of increases

One place to look for a possible solution to this problem is Zhejiang province, which also serves as a ‘Common Prosperity’ pilot zone. Coincidentally, it was a Zhejiang court, which ordered Huang Wei, the live-streamer, to pay the record fine for tax evasion. Nevertheless, tax policies – especially for small businesses in the province’s hugely important export sector – remain favourable. A press release from October 2021 noted that tax cuts in the province had surpassed RMB 200 billion (around £28 billion) in the first three quarters of the year.

To provide better funding for poorer areas despite tax cuts, Zhejiang wants to create a transfer mechanism that would funnel money from its affluent capital Hangzhou and export hubs like Ningbo and Yiwu, to less well-endowed parts of the province. What’s more, a plan for ‘Fiscal Promotion of Common Prosperity’ published in December 2021 also proposes a system that would direct more central government support to cities which absorb large numbers of labour migrants – a group which, so far, is not covered by local government services. In short, the plan aims to create a province-wide budget process that can allocate money across administrative boundaries.

What Zhejiang’s approach suggests is that integration and optimisation – and not an increase – of both tax collection and expenditure remain the principal tools for China’s fiscal policy in the age of ‘Common Prosperity’.

The CBBC view

China’s fiscal carrot-and-stick approach carries some significant risks for businesses. On the one hand, additional tax benefits and exemptions seem to be good news, and the breaking down of administrative tax barriers benefits companies, too, as this makes it easier for companies to relocate within China.

On the other hand, the tax authorities’ ever-improving ‘panopticon’ requires a more comprehensive accounting approach to operations, especially if a company is active in multiple locations across China. An office-by-office approach and localised accounting might have to give way to a nationwide management strategy. Businesses should also be careful when registering companies in low-tax jurisdictions such as Wuxi, Dongyang, or Songjiang district in Shanghai. As the cases against live streamers have demonstrated, income improperly recorded in these tax districts might be perceived as tax evasion by other Chinese jurisdictions.

Finally, Beijing’s penchant for seeking out high-profile targets to act as an example to others – an approach best described by the Chinese proverb ‘kill the chicken to scare the monkey’ – is probably the largest source of uncertainty. For example, marketing strategies relying on KOLs will require more due diligence to make sure that campaigns do not collapse midway through because of a sudden tax investigation. Creative industries, too, will have to pay greater attention to the contractual arrangements of actors, artists and freelancers.

Overall then, it seems tax inspection rather than tax rises will be the main concern for businesses in the new age of ‘Common Prosperity’.