China’s harsh Zero Covid policy is putting huge pressure on the Chinese economy, with April’s data indicating a sharp downturn. The government wants to increase infrastructure spending and do more to help SMEs while also keeping employment stable, according to CBBC’s policy team, Torsten Weller and Joe Cash – so how likely are they to pull that off?

Worries about the Chinese economy are mounting. Despite respectable growth of 4.8% for the first quarter, several indicators paint a more sombre picture. Consumption data, in particular, rattled policymakers. In March, the retail sales of consumer goods decreased by 3.5% year-on-year, down from a 6.7% increase in the first two months of the year.

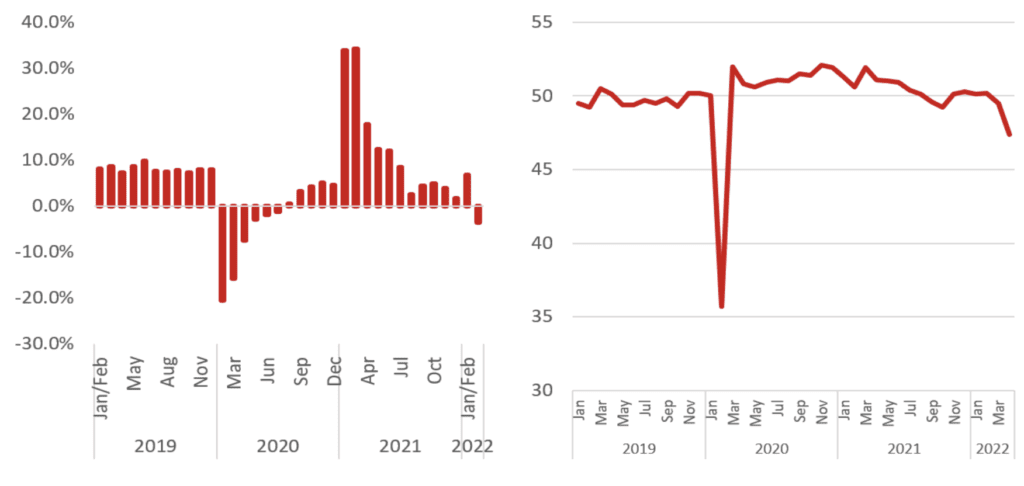

Last month’s data confirmed Beijing’s concerns. April’s Purchasing Manager Index (PMI) – which measures the Chinese manufacturing sector – dropped to 47.4, the lowest figure since the beginning of the pandemic. Export data, too, weakened in April, growing only 3.9%, the lowest monthly growth since June 2020.

To stabilise the economy, the Chinese government has issued several guidelines ahead of this year’s Communist Party Congress, which is expected to select President Xi Jinping for a historic third term. Yet while most of the recent announcements targeted infrastructure and job security, it will probably fall – once again – onto China’s strong export sector to save the economy and lead the recovery.

Background

Though recent figures may still be a far cry from the dramatic slump during China’s first lockdown, the global situation is much less favourable than it was in early 2020. Back then, most countries were just about to enter lengthy lockdowns themselves. Central banks around the globe were switching on the money printers to keep their economies from collapsing, and customers in advanced economies had cash to spend, as they were saving on commuting costs and other expenses. Now the situation is exactly the opposite. Most developed economies have exited lockdowns and are returning to pre-pandemic levels of economic output, monetary supply is tightening, and soaring inflation is squeezing households.

And it’s not just Chinese policymakers that are worried. Foreign businesses and investors are also growing weary of the country’s economic troubles. A recent flash survey by the European Chamber of Commerce in China (EUCCC) showed that nearly 60% of participating companies had reduced their revenue predictions for 2022, and about a quarter were considering shifting investment to other markets. In February and March, foreign investors pulled out of RMB 193 billion (£23.3 billion) worth of Chinese bonds – the greatest outflows since the beginning of China’s bond market. At the same time, early-stage investment by VCs declined by 90% year-on-year in the first quarter of 2022.

To reverse the trend, the Chinese government has released a series of policy guidelines to stabilise the economy. Four areas are crucial: infrastructure, domestic consumption, jobs and trade. This update will look at each of them and highlight the key challenges.

Year-on-year retail sales growth (left) and 2019-2022 official manufacturing PMI (right) (Source: National Bureau of Statistics)

Infrastructure

Since the financial crisis in 2008, infrastructure spending has been the default lever for Chinese policymakers to stimulate growth. So it didn’t come as a surprise when, on 26 April 2022, the Central Committee for Financial and Economic Affairs – the Party organ overseeing economic and financial policy – announced a slew of new measures to speed up infrastructure spending across the country.

Most of the areas targeted relate to logistical choke points like transport networks and waterways. Logistics and supply chains were a natural victim of lockdowns with truck traffic in March 2021 dropping to 40% of normal levels. In Shanghai, traffic plummeted even further to only 15%, according to the South China Morning Post. Other areas of investment include 5G networks, renewable energy and data centres.

Improving transport links and investing in next-gen technologies, therefore, certainly makes sense. However, speeding up infrastructure spending now also means that many of the RMB 14.8 trillion yuan (£1.8 trillion) worth of planned projects will be front-loaded. This could boost growth now but lead to weaker economic activity later this year.

Consumption

Besides infrastructure spending, stimulating consumption is another top priority. In a strategy paper on domestic consumption published on 25 April, Covid takes the top spot. The paper outlines several measures the government should take to alleviate the damage caused by the recent lockdowns:

- Reduce taxes and fees

- Ease access to financing and bank loans

- Suspend interest payments and fee collection (e.g. rents, electricity bills)

- Offer special support measures for retail, hospitality and tourism sectors

- Optimise online service innovation to allow businesses to stay open during lockdowns

The policies outlined here are in line with the measures taken during the previous lockdown in 2020 and conform to the Chinese government’s general emphasis on ‘supply side’ measures to support the economy.

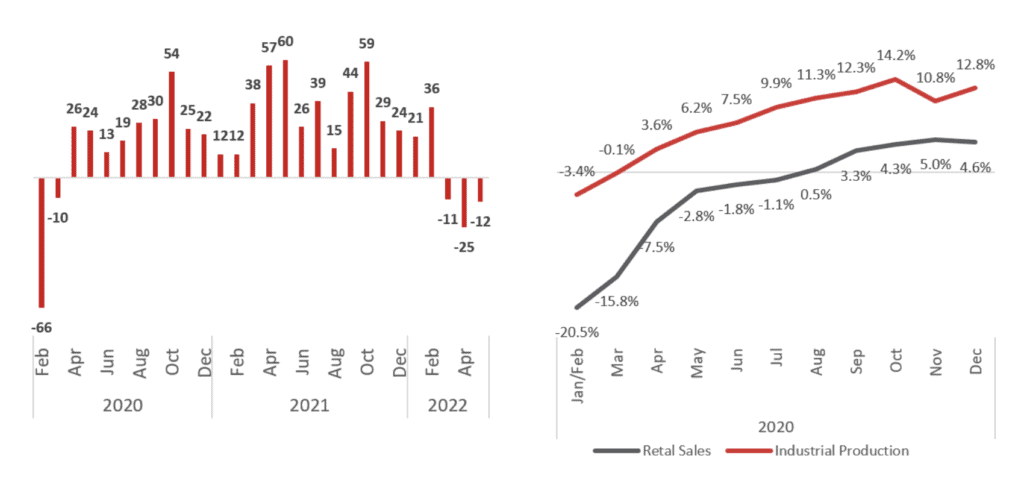

It remains questionable, however, whether they will be enough to ensure a speedy recovery once the lockdowns are lifted. Official data from 2020 shows that retail and hospitality sectors took much longer to recover than manufacturing, which returned to positive growth in April 2020. Retail sales, on the other hand, did not recover until August 2020.

A recent mobility heat map shared by Natixis – a French investment bank – also indicates that it might take longer for a return to normal than in 2020. According to Natixis’s calculations, mobility across China was below the 2019 average in May for the third month in a row. By contrast, in 2020, mobility levels had returned to growth after only two months.

Employment

Related to both infrastructure and consumption is, of course, employment. Job creation was a major theme in this year’s Two Sessions and was highlighted as a particular challenge by Premier Li Keqiang himself during his press conference at the end of the annual meeting in March.

According to the latest data, jobs did indeed take a hit during the latest lockdown round. Urban employment rose to 6.1% in April 2022, the highest level since February 2020. More worryingly, the impact of lockdowns is now compounded by a series of long-term effects, such as the recent wave of redundancies made by China’s tech giants. According to TechNode, nearly 73,000 tech employees lost their jobs between July 2021 and mid-April 2022.

Although current lockdown measures can probably provide occupation for some unemployed workers, the situation is expected to become graver the longer the current lockdowns last. In a statement published on 7 May, Premier Li Keqiang has warned provincial leaders of a grim outlook for China’s job market and has urged policymakers to do everything they can to ensure stable employment.

Yet whether the country can – in fact – achieve its self-set goal of 11 million new urban jobs this year, will also depend on whether it can get China’s export machine back on track.

National mobility levels since 2020 (left) and industrial production and retail sales growth in 2020 (right) (Source: Natixis, National Bureau of Statistics)

Trade

Chinese exports were undoubtedly the main engine of the country’s post-Wuhan-lockdown recovery. Outbound shipments soared 29.9% year-on-year to a historic level of USD 3.3 trillion (~£2.7 trillion) last year. So, given their preeminent role during the recovery, the drop in exports compared to the previous month is clearly worrying. Even though the value of exports in April – USD 273.6 billion versus USD 276.1 billion in March – remained comfortably above pre-pandemic levels, the timing of the slowdown comes at an unfortunate moment.

As the Chinese business magazine Caixin reported, the lockdown is hitting season-sensitive industries like textile manufacturers – many of which are concentrated in the Yangtze River Delta – particularly hard. One producer told Caixin that if restrictions weren’t loosened before the end of May, his company might lose out on orders for the rest of the year, meaning that exports could suffer for the whole of 2022.

What makes the situation worse for these industries is that other labour-intensive and export-oriented economies such as Vietnam and Indonesia are already exiting their own lockdowns and are increasing export volumes. This could accelerate the already existing offshoring trend among some Chinese industries towards lower-income countries. In this case, some jobs would then be gone for good.

While China’s overall export levels will probably remain above pre-Covid levels this year, the potential long-term damage for Chinese exporters – and the related negative knock-on effects on employment – will put growing pressure on Chinese policymakers to find a viable exit strategy for its current Covid policy.

The CBBC View

Getting the economy back on track will be one of the major tasks for the Chinese government in the coming months. Although there is still a huge amount of uncertainty regarding the country’s inflexible Zero Covid policy, CBBC expects economic recovery to take precedence over harsh lockdowns and quarantine rules.

Although the current focus is mostly on infrastructure spending and consumption, we also expect that manufacturing and exports – and not domestic retail – will once again play the role of the workhorse for China’s recovery. Past experience and recent mobility data suggest that Chinese consumers will probably remain cautious and fearful of further lockdowns. It might therefore take even longer for retail levels to recover than in 2020.

It is also worth noting that an economic recovery entails its own risks. First, there is inflation. At 2.5%, China’s CPI in April remained far below the price increases seen in North America and Europe. Without the deflationary pressure of lockdowns, however, Chinese consumers could thus be faced with similar price hikes, especially as Chinese factory prices have been consistently more than 10% higher than last year’s numbers over the last couple of months.

And then there are jobs. The already high unemployment rate might further rise especially as tax holidays for Chinese SMEs are supposed to end in June. It is also likely that current lockdown measures mask some of the unemployment as jobless workers are mobilised to testing and quarantine facilities.

Given these risks, it is to be expected that the Chinese government will extend tax and social insurance fee holidays beyond June and potentially launch yet another stimulus package in the second half of the year.