Li Keqiang’s economic policy – called Likonomics – has received new attention as China seeks to recover from the latest Covid outbreak, but weak domestic demand and a struggling property sector might force Chinese leaders to abandon Likonomics at the next Party Congress in autumn, writes Torsten Weller

The dramatic weakening of China’s economic performance – caused by the lockdowns in Shanghai and other big cities – has prompted Premier Li Keqiang, who is in overall charge of China’s economic policy, to assume a far more prominent public position. While this shift in media attention has led to speculation about a potential split within the top ranks of the Communist Party (CCP), the main question lies elsewhere: will Li’s policies to revive the struggling Chinese economy actually work?

Li Keqiang’s distinctive policy approach – often dubbed Likonomics – prefers supply-side measures and strict budgetary discipline to large-scale monetary stimuli and big-ticket infrastructure investment. Although China’s debt binge in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and the soaring public debt levels make Li’s policy choice look reasonable, questions are being raised over whether they are the right tools to deal with the economy’s most pressing problem: weak domestic demand.

What’s more, Li’s emphasis on tax cuts and lower social security contributions to support businesses puts further pressure on local government budgets, which have already been battered by years of debt accumulation and rising demand for social services. If one adds the increasing cost of extended lockdowns and preventive measures to the mix – which are also financed out of local coffers – then it becomes more and more apparent that Li’s policy approach might not be fit for purpose.

Both a continuation and an abandonment of Likonomics could have important consequences for foreign businesses in China.

Likonomics isn’t a new term. In fact, it was first coined in the early days of Li’s premiership. In June 2013, only months after his official appointment as the head of the State Council, Huang Yiping, a professor at Peking University, together with two analysts at Barclays Capital, Jian Chang and Joey Chew, published a report entitled “What to expect from Likonomics?”.

Initially conceived as the opposite to ‘Abenomics’ – a reference to Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s lacklustre attempt to revive Japan’s sluggish economy – Likonomics was not about stimulating growth, of which there was more than enough in China, but rather it focused on transforming it from the debt-driven model of the Wen Jiabao era into a more sustainable, long-term model able to lift China into the ranks of high-income developed economies. As Huang Yiping wrote back then: “Likonomics is about deceleration, deleveraging and improving the quality of growth.”

Yet marketing jargon aside, Likonomics isn’t a specifically Chinese affair. As the Economist noted, Li’s three ‘arrows’ – no stimulus, deleveraging, and structural reform – were surprisingly similar to the austerity measures adopted by other countries – including the UK – following the financial crisis of 2008.

Globally, Li’s policies are in line with the Summit Declaration of the 2010 G20 meeting in Toronto, of which Li himself – then still an apprentice Vice-Premier under Wen Jiabao – was probably aware. As the declaration stated, G20 countries should be:

“Following through on fiscal stimulus and communicating “growth friendly” fiscal consolidation plans in advanced countries that will be implemented going forward. Sound fiscal finances are essential to sustain recovery, provide flexibility to respond to new shocks, ensure the capacity to meet the challenges of ageing populations, and avoid leaving future generations with a legacy of deficits and debt.”

Fast forward to 2022, and these words remain remarkably relevant. At the press conference following this year’s Lianghui (Two Meetings) in March, Li Keqiang stuck firmly to these twelve-year-old recommendations. Not only did Li emphasise that China’s national budget deficit had been further reduced to 2.8% last year – a number which would make a German finance minister proud – he also highlighted the positive effect of tax cuts on overall government revenue, highlighting the main argument of Western pro-austerity advocates.

Yet, while these policies make sense in an environment where economic growth is high and wages are rising, it is less suitable when dealing with slowing growth and weak domestic demand. Yet this is exactly the problem the Chinese government is currently facing.

GDP growth in Q2 is expected to be weaker than the already low 4.8%, recorded in the first three months of 2022. Two of China’s main growth drivers – real estate and consumption – are still in the doldrums. Residential property sales in May recorded their ninth consecutive month of decline, dropping a further 41.7%. According to Bloomberg, cumulative housing sales as measures in square metres are now at the lowest level since 2016.

Consumption, too, is sluggish. According to the latest figures published by China’s National Bureau of Statistics, retail sales in the first five months of 2022 decreased 1.5% year-on-year. In May, overall consumption declined by 6.7% year on year, with food services alone down by more than a fifth compared to last year. And while the drop in consumer spending is less severe than at the beginning of the pandemic, the hit to consumer confidence is far more damaging. In April, China’s consumer confidence index fell – for the first time since 2016 – below the 100-mark to 87.6. As a comparison, in 2020 at the height of the first Covid wave, confidence only dropped to 112.6.

With both growth engines seemingly very suppressed, and expectations trending downwards, Li’s approach of fiscal consolidation and tax cuts might not be enough to get the economy back on track. While in late May the government announced 33 measures to support the economy, none of them supports the demand-side directly. Instead, infrastructure, manufacturing, and foreign trade remain the principal levers for Beijing.

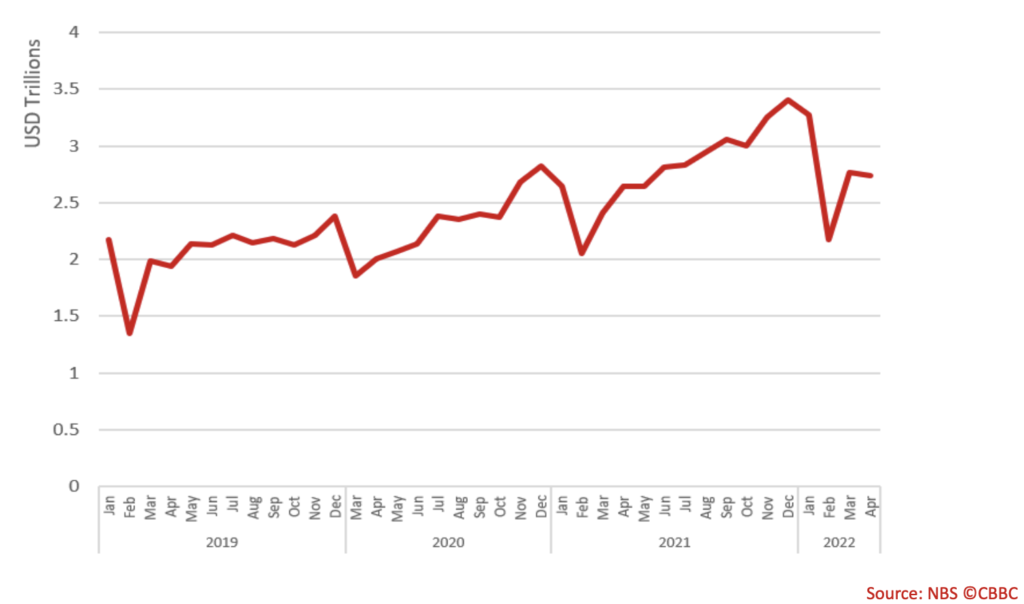

Paradoxically, with Likonomics unable to boost domestic demand, China’s government is thus forced to revert to exports as the country’s main growth driver. Since the beginning of the pandemic, Chinese exports have jumped from one record to the next. Even in April 2020, exports where still over 30% higher than the monthly average of 2019. And with the world economy slowly recovering, these numbers will remain high for the foreseeable future.

What this means, however, is that China’s much-touted rebalancing away from an export-led growth model and its emphasis on ‘dual circulation’ and ‘common prosperity’ might well struggle to get off the ground without some fundamental policy change. Likonomics – as it turns out – could deepen rather than weaken China’s reliance on global trade and foreign markets.

Chinese exports since 2019

The CBBC View

For foreign businesses, Likonomics has undoubtedly had some benefits. Lower taxes and fees, as well as supportive trade policies, have boosted manufacturing – especially in export-oriented sectors. Yet the policy’s heavy reliance on foreign markets and the lack of support for domestic demand also means that China’s internal market might struggle to replace exports as the country’s principal growth engine anytime soon.

Yet with Li Keqiang stepping down by the end of the year, there is also a chance of a significant policy change. Xi Jinping’s commitment to ‘common prosperity’ and domestic consumption as a principal source of economic growth remains unchanged and means that – sooner or later – demand-side policies will have to take the lead. Whether China’s next Premier is ready to abandon his predecessor’s commitment to a balanced budget is therefore one of the most important questions – not only for China’s own future development, but also for global trade in general.