The biggest trade bloc in history, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, provides its member states with a tariff-free route into the China market. However, as Joe Cash explains, China’s membership brings challenges as well as opportunities

Just after the stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve, trade negotiators in Australia, Brunei, Cambodia, China, Japan, Laos, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand and Vietnam likely raised a second toast congratulating themselves on a job well done in getting the biggest trade bloc in history up and running. It has been a long and hard slog. Negotiations took close to a decade, and the membership of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement does not, at first sight, give the appearance of an easy alliance.

The new bloc consists of a mixture of developed and developing states, whose economic policies run the full length of the spectrum, from free trade stalwarts such as Japan and New Zealand, to countries in which ‘economic planner’ is a much sought-after position in the civil service. What unites them is a common desire to move the centre of gravity in global trade even further eastward.

Britain’s Department for International Trade (DIT) has shown a keen interest in the bloc. While the trade deals that the UK has agreed with Australia, Japan and New Zealand probably provide Britain’s trade negotiators with a sufficiently robust foot in the proverbial door, the Pitcairn Islands – a British Overseas Territory in the Pacific Ocean of relative unimportance pre-Brexit – provide further cause for an application for membership from Whitehall to receive the current RCEP members’ consideration. Although likely, a formal application from Britain might take a while: despite its size, the RCEP is not the big prize for the UK in the Asia-Pacific region. That award goes to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) – the poster child of liberal, free trade. But that does little to diminish the impact the RCEP will have on Asia-Pacific trade. The RCEP is big. That is its draw.

The RCEP is also the only trade bloc to contain China, which goes a long way toward explaining why it is quite so big. China’s membership of the RCEP presents opportunities and challenges for the UK. On the one hand, by joining the RCEP, UK companies would gain tariff-free access to the China market. On the other, the UK would have to agree to a pre-determined set of rules that would give China tariff-free access to its market. For many disparate reasons, that is a tough call to make.

Background

The RCEP was first touted by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2012 as a way of tidying the various competing Free Trade Agreements (FTA) its members had in place but which were incompatible.

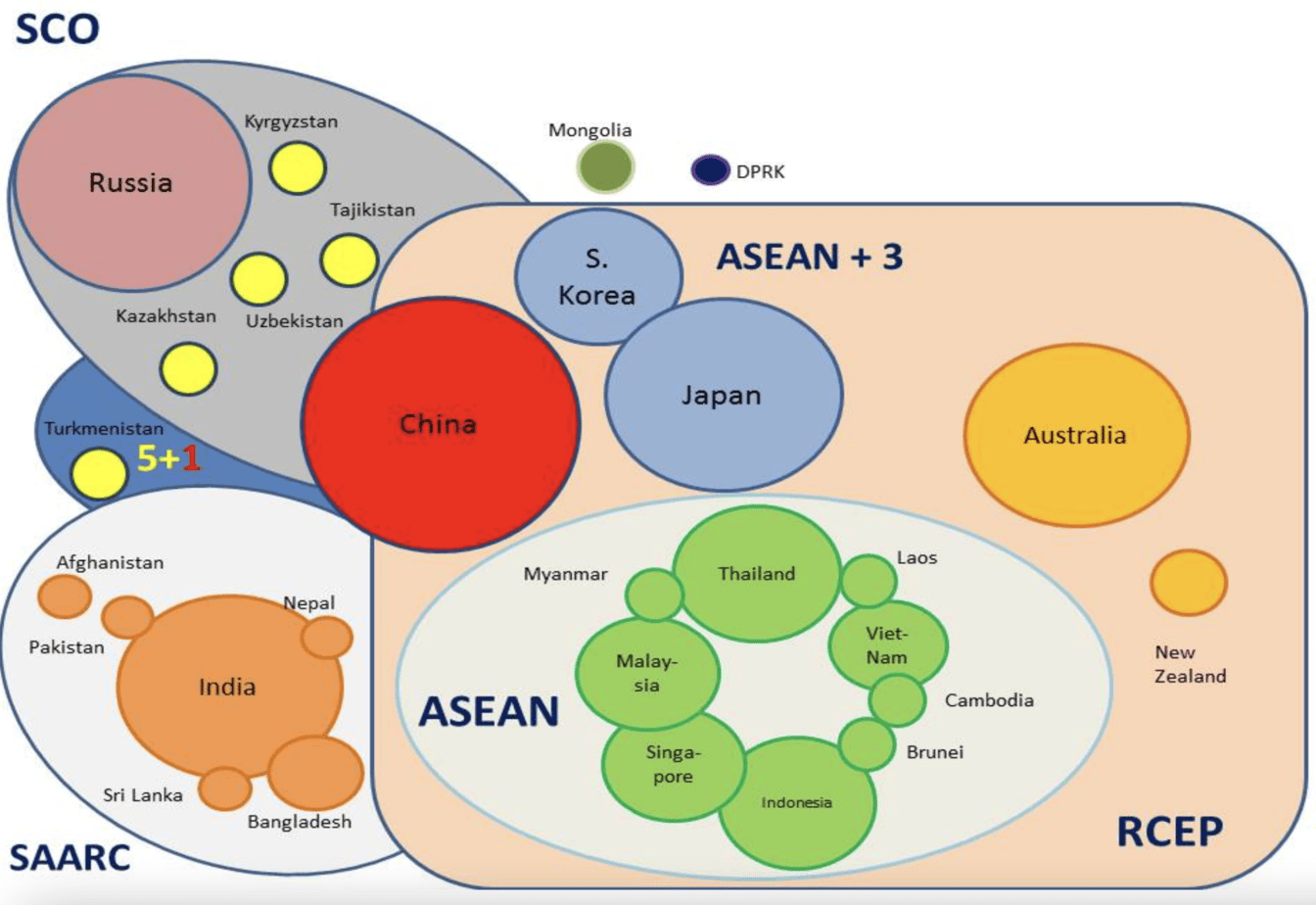

Negotiations got underway in Brunei the following year, and at that time, both China and India – the two big beasts of Asia-Pacific trade – were tentatively backing its progress and indicating their interest in joining the final agreement. New Delhi would later drop out of the negotiations, fearing that China would come to dominate the arrangement and flood the Indian market with cheap manufactured goods, but 15 other markets remained to see the talks through to completion – the 10 ASEAN states (Brunei, Laos, Cambodia, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam) and five partner countries (Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea). After ratification, that would see the RCEP’s member states account for 30% of the world’s population, and 30% of global GDP.

While it is early days, analysts expect the RCEP to eliminate around 90% of tariffs on imports between the 15 signatories (although, for technical reasons, there are currently only 11 active members) and establish common rules for e-commerce, trade, and intellectual property, as well as a unified framework for Rules of Origin. As a result, the deal could add over $200 billion to global incomes annually, and $500 billion to world trade by 2030, according to estimates from the Brookings Institute.

While the RCEP goes a considerable way toward addressing the melee of deals in the Asia-Pacific region, it remains very congested when it comes to trade agreements – there are some 30 countries split over seven economic organisations. However, it is because of the sprawling nexus that these free trade disagreements constitute the Asia-Pacific region becoming the new world centre for the movement of goods and people.

How does the RCEP intersect with the ASEAN free trade zone and the CPTPP?

What are the key features of the RCEP?

The RCEP agreement runs to 20 chapters and covers most of the areas expected from a free trade agreement, with the exceptions being a lack of text on labour and environmental protections.

Trade in Goods: One of the most eagerly anticipated aspects of the RCEP is that it will simplify customs arrangements across the region. The text of the agreement seeks to reduce the compliance burden on companies exporting goods, including provisions allowing the release of express consignments and perishable goods within six hours after arrival.

Trade in Services: While most of the RCEP’s benefits are to be found in trade in goods, at least 65% of the signatories’ services sectors will become fully open to foreign investment under its terms. Member states have committed to raise the ceiling for foreign shareholding limits in their respective markets across industries including professional services, telecommunications, financial services, IT, and logistics. A ‘negative list’-style approach will also be introduced across the bloc, whereby if a market does not appear on the list, investors can assume it is open to foreign investment.

Rules of Origin & Cumulation: One of the RCEP’s main benefits is that it will iron out discrepancies between the different ASEAN free trade agreements with Japan, South Korea and China regarding rules of origin and cumulation. Until now, if a table manufacturer in Indonesia wanted to export tables containing components obtained from across the ASEAN bloc, they could not export the exact same table to both Japan and South Korea. This is because Indonesia’s FTAs with Japan and South Korea have different cumulation requirements, meaning that the manufacturer must assemble the table using different components to sell into both these markets.

Investment: The text of the agreement includes provisions that will make it easier for foreign investors to enter the markets of other RCEP members. The text also includes a built-in investor-state dispute settlement mechanism that can be invoked by member states. This may become a bone of contention should the US seek to accede to the agreement, however.

E-commerce: The e-commerce text aligns closely with that which was agreed for the CPTPP. With provisions strengthening the rights of IP rights holders online and measures to improve the protection of personal information online, member states are hoping RCEP will help spur an e-commerce boom across the region. However, critics have pointed out that while the provisions are stronger than those currently on offer in the Asia-Pacific region, they are not as sophisticated as those within the CPTPP or EU FTAs.

Public Procurement: The measures outlined in the text should improve transparency across the region in terms of public procurement. The RCEP member states have committed to publishing their laws, regulations and procedures regarding public procurement, as well as tender opportunities to supply their respective governments if available.

The RCEP is a big deal, both in terms of GDP and how it will change the dynamics of Asia-Pacific trade.

China and the RCEP

Beijing took a back seat in the RCEP negotiations. One can speculate that China took such an approach for two reasons: (a) to avoid being cast, as New Delhi eventually sought to, as a domineering presence that would take advantage of any concessions to which the other signatories committed; and (b) because China wants to use membership of the RCEP – along with its application to join the CPTPP and the Digital Economy Partnership (between Chile, New Zealand and Singapore) – to demonstrate it is a mature and capable actor in multilateral trade.

China will proactively use the terms of the RCEP to further its economic influence in the region. In addition to the RCEP, CPTPP and the Digital Economy Partnership, Beijing has also been dabbling in a tripartite trade agreement with South Korea and Japan. The country clearly wants to expand its tariff-free routes to export within the region. As all three countries are now members of the RCEP, the China-Japan-South Korea deal is probably moot, but it demonstrates that expanding Beijing’s free-trade ties has been on the mind of the country’s economic planners for a while now.

While China expanding its economic reach within the Asia-Pacific region will, undoubtedly, become a cause for concern among British MPs – who might also move to block any future attempt by the UK to accede to the bloc due to China’s membership, as the US includes wording in its FTAs that forbids its trade partners from entering into third agreements with non-market economies (read: China), for one – it does present an opportunity for multinational UK companies with subsidiaries in RCEP member states. Just as China enjoys tariff-free access to the markets of other RCEP member states, so too can any registered subsidiaries of a British MNC utilise the terms of the agreement to gain preferential access to China. Note, this is not without its problems.

The CBBC view

The RCEP is a big deal, both in terms of GDP and how it will change the dynamics of Asia-Pacific trade. When one considers that it sits adjacent to the CPTPP, which is in itself another massive deal, it is clear that global trade is moving increasingly eastward. However, the various trade agreements on offer in the Asia-Pacific region are all underpinned by different FTA models, which is causing regulatory divergence that could spill over to affect international trade more broadly. Whilst this might bring with it some short-term benefit to UK MNCs with subsidiaries in the member states of the constituents of the various deals, provided their supply chains can be arranged to tap into them, the RCEP’s advance might not be a good thing for UK plc in the long term.

Its terms and conditions suit markets such as China and Vietnam that prefer to take a more dirigiste approach in running their respective economies because they are nowhere near as ambitious as those of the CPTPP or the EU’s FTAs. For this reason, it makes sense for the British government to continue to back the CPTPP – as it is doing so through its application to join – in the context of APAC FTAs. The RCEP is a shortcut into China for locally-based British subsidiaries, but it is debatable whether it would be worth opening the UK domestic market and watering down its regulatory regime to use this route.