The UK has done well through partnering with China on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) before, but is it now considering extricating itself from further BRI collaboration with Beijing to align itself with the US or the EU? Joe Cash investigates

A global contest is brewing. China, the US, and the EU are all vying for influence along routes that Beijing first turned its attention to in 2013 when President Xi announced his Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), that would bring the ancient Silk Road into the present day. It hasn’t always been this way. In the years preceding the outbreak of Covid-19, cooperation was the name of the game when it came to the BRI. In 2019, while attending the BRI Forum in Beijing, Britain’s then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Phillip Hammond, came close to signing a Memorandum of Understanding that would have given Beijing Britain’s backing. Fast forward to the present day, and the US is spearheading the creation of the Build Back Better World (B3W) initiative within the G7, while the EU has unveiled plans to launch a “Global Gateway” scheme.

So how does Britain fit in? And why is a country that once called the BRI “an extraordinarily ambitious vision” now debating whether it would be better throwing its lot in with Brussels and Washington?

Background

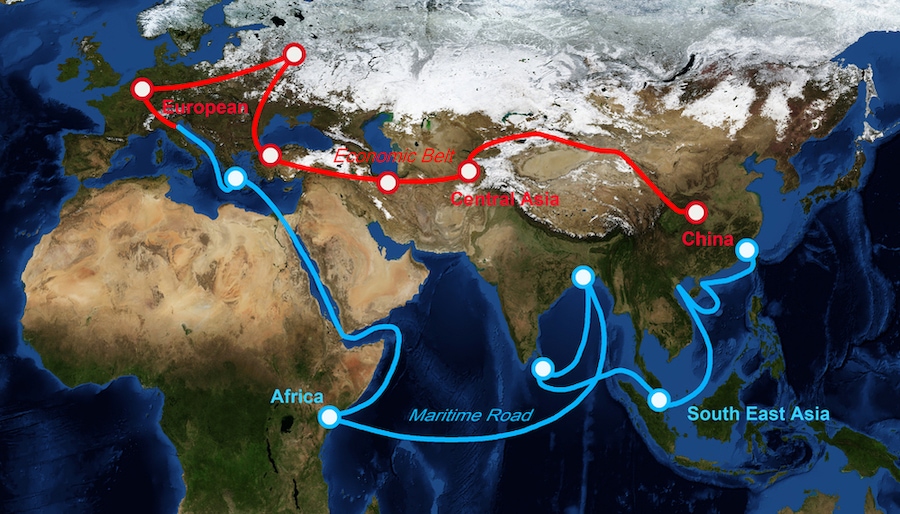

The BRI, also known as One Belt, One Road (OBOR), is one of the main load-bearing pillars of the Xi administration’s foreign policy. A diverse portfolio of overseas investment and construction projects rolled into a new, China-led model for interactions between countries, combined with a channel through which to transfer Chinese overcapacity, the BRI certainly is, as Phillip Hammond once noted, “a project of truly epic ambition.”

Stretching from China into Europe and traversing the continents of Central Asia, Africa, and the Arctic, China uses the investments its state-owned banks and companies makes along the route of the BRI to deepen its access and influence on the world stage, particularly in the Global South. Chinese banks and corporations have made over $2 trillion in foreign direct investments since 2005. The Trump administration worked hard to brand these investments as part of a “predatory lending programme” or a “debt trap,” but this claim has been widely refuted.

The prevailing view among scholars studying the BRI and how it fits into China’s new globalism is that there is no such “debt trap,” nor is China doing anything untoward to exploit the countries once its firms have invested. Research shows that China has never actually seized an asset from any country owing funds and that Chinese banks are willing to restructure the terms of existing loans. As such, the prevailing motivation behind the West’s increasing desire to provide an alternative is to halt the spread of the ‘China option.’

If that is the case, then the clock is ticking, and China has a clear first-mover advantage. Chinese companies have become more professional in their dealings overseas. Meanwhile, the governments of the countries within which Chinese entities focus their investments seem to find the alternative financial and legal institutions that are being set up in parallel to the Bretton Woods system, to handle BRI disputes, to be very appealing. Distinguishable by their informality, ad hoc design, and preference for soft law over systematic formal rules, whether China plans to align its terms and conditions with international (read: Americanised) best practices remains unclear.

What are the Western alternatives to the BRI?

It might be too little too late to halt China’s emergence in the Global South. It could be that there is just too much Chinese capital flowing through these emergent economies already, rendering the West’s efforts to dissuade BRI countries from subscribing to China’s offer of an “Asian model” of economic development a futile endeavour.

That said, the US-led, G7 B3W initiative plans to narrow the “$40 trillion in infrastructure investment that developing countries will need by 2035”; $2 trillion has already been committed by the US, with other G7 members currently considering their contributions. Compared to the infrastructure focus of the BRI, the B3W initiative targets areas such as climate health, digital technology, gender equity, and health security, and is heavily private sector-led.

Brussels, meanwhile, has announced the Global Gateway (GG), a spending plan that will see $300 billion directed at countering China’s economic influence, predominantly across the African continent. Like B3W, GG is private sector-led and the text of the initiative specifies that it is about “rule of law, human rights, and international values.”

Where does the UK fit in?

The UK is a member of the G7, so presumably will transition its tacit support for the BRI to the US-led initiative, B3W. Foreign Secretary Elizabeth Truss has already indicated that she plans to align her department with the initiative’s objectives. What this means for UK-China relations depends on how closely the Johnson cabinet seeks to align its departments with their counterparts in the Biden administration. Were the UK government to pursue a policy of exclusive alignment with B3W, that could create complications with China because the Department for International Trade and the National Development & Reform Commission still have a Memorandum of Understanding in place from the 2019 Economic & Financial Dialogue focussed on third market cooperation (Read: BRI).

While the British government has kept its cards close to its chest concerning B3W – which remains scant on detail – and has not revealed its formal intentions vis-à-vis aligning with America’s vision, the UK and China reportedly plan to hold an economic and financial dialogue (EFD) in 2022, which could put pressure on the Johnson government to choose sides. Given that the UK and China have successfully delivered on almost all the outcomes agreed at the previous meeting, it is hard to see a palatable diplomatic exit ramp – for want of a better expression – for DIT to use should it want to extricate itself from further UK-China collaboration along the BRI. Ms. Truss has been far more hawkish towards China, however, so it will be up to the Prime Minister to bring the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office into alignment with DIT on further cooperation with China along the route. DIT, rather than the FCDO, currently coordinates the bulk of UK cooperation with China relating to the BRI.

The CBBC View

The BRI could become awkward for Britain as it tries to juggle asserting itself as a prominent, global trading nation and being a determined defender of multilateralism and the rules-based order. British firms have done well through partnering with Chinese state-owned enterprises along the route, particularly in the built environment and financial and professional services sectors – as a result, the British and Chinese governments have managed to tick off all the policy outcomes relating to the BRI from the last EFD. The BRI differs substantially from the US and Europe’s new offerings; it does not share their values-based approach for a start. Underlying the initiative is the idea that China is just as capable as the US in global leadership and governance – could cooperation along the route become the next area where the UK comes under pressure from the US and China to choose a side?