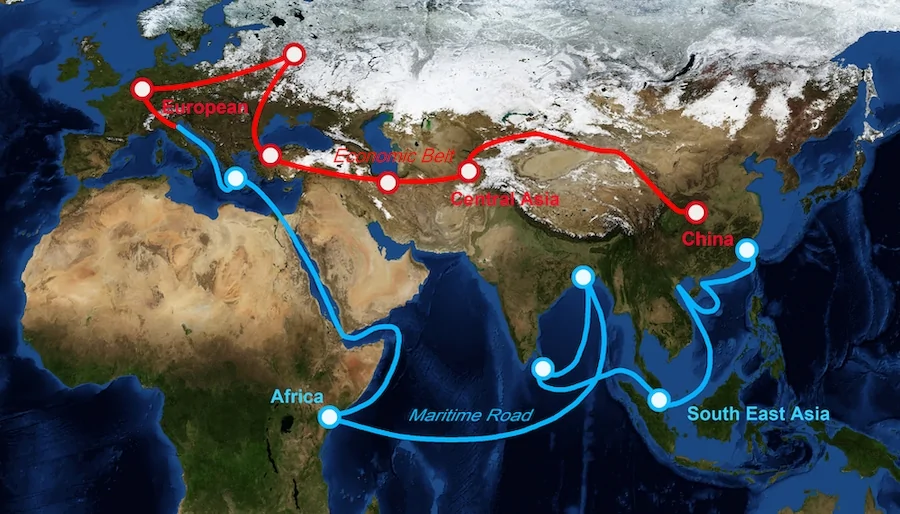

In October 2023, China hosted the Third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing to mark 10 years of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Officially dubbed the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, the BRI is an ambitious (and sometimes controversial) infrastructure development strategy that forms the centrepiece of Xi Jinping’s foreign policy strategy.

On the 10th anniversary of the BRI, we look at 10 key figures that demonstrate the scale and ambition of the project.

155

As of August 2023, a purported 155 countries have joined the BRI by signing a memorandum of understanding (MoU). According to the Chinese government’s Belt and Road Portal, this includes 40 countries in Asia, 52 countries in Africa, 27 in Europe, 15 in North America, 9 in South America, and 12 in Oceania.

1

Italy is the only G7 country to have joined the BRI, having signed an MoU with Beijing in March 2019. However, as of late 2023, the Italian government has indicated that it is likely to withdraw from the BRI, bringing it into step with the China policy of the rest of the EU. Italian politicians are reported to have been disappointed with the scale of trade and other business dealings with China since the MoU was signed.

$1 trillion

The amount estimated to have been spent on BRI initiatives, making the BRI the largest multilateral development project ever undertaken by a single country.

3,000

The number of major projects estimated to have been undertaken as part of the BRI. This includes roads, railways, ports, power plants and other critical infrastructure.

40%

The proportion of projects in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor – one of the BRI’s flagship arrangements – estimated to have run into problems such as funding cuts, corruption, or insurmountable cost increases. Some have criticised BRI projects for a lack of follow-through, leaving countries with infrastructure projects and economic zones that ultimately do not contribute to the economy. A report by AidData at William & Mary suggests that around a third of the BRI infrastructure project portfolio has encountered major impediments.

120km per hour

The speed of the trains on the China-Europe Railway Express project, a logistics distribution network that connects China with more than 200 cities in 25 European countries via the Eurasian hinterland.

36 gigawatts

The estimated capacity of the coal power plant projects that have been cancelled since 2021 after Xi Jinping announced that China would no longer support the construction of coal-fired power plants abroad. Since then, China has stated its commitment to supporting green and low-carbon energy development in BRI countries.

13,000km

The length of the Yiwu-Madrid railway line, the world’s longest railway freight route (the Yiwu-London route is the second longest). The route is one of several used by long-distance trains as part of the “New Eurasian Land Bridge”, which is integrated with the BRI. The journey takes around three weeks, as opposed to six by sea. Despite the success of China-Europe rail projects over the past decade, most analysts agree that the maritime routes of the BRI still receive the most focus/trade.

99 years

The length of time that the Hambantota International Port in Sri Lanka has been leased to China. China Merchants Port took a 70% stake in the port in 2017 after the Sri Lankan government struggled with debt repayments (the construction of the port had been financed with commercial loans from the Exim Bank of China). Hambantota has been used as an example in accusations that China is practising ‘debt-trap diplomacy’, in which a country extends debt to another country to increase political leverage. However, the ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ hypothesis about the BRI has not been universally accepted by economists and IR specialists.

10,000

The number of scientists from BRI countries that have visited China for research or exchanges. Over the past few years, cultural, digital, and health-related initiatives have been playing an increasingly important role in the BRI, with the focus shifting to “softer” power initiatives, including personal training and the construction of cultural institutions.