China plans to increase domestic consumption by at least 6% in 2021, but the large rural income gap, low education levels and rising household debt pose significant challenges, writes Torsten Weller.

Increasing domestic consumption has become one of Beijing’s major concerns. The 14th Five-Year-Plan, which was adopted in March, sets out an aim for Chinese disposable income to grow at least as fast as GDP . With this year’s economic growth target set at 6% , this means that household spending should rise by at least the same amount.

Domestic consumption is also a key component of the government’s new Dual Circulation Strategy, through which it plans to turn the country’s vast consumer market into an irresistible magnet for foreign investment and businesses.

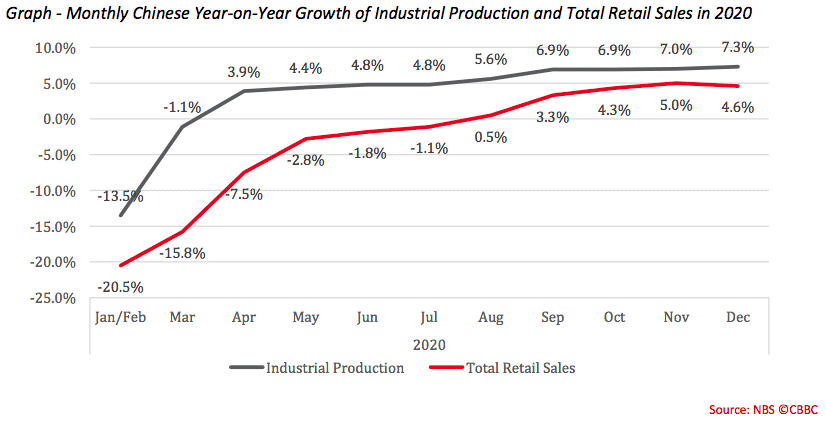

Yet achieving this goal will require significant reforms. The Covid-19 pandemic has laid bare the weakness of China’s domestic retail sector. Not only was it harder hit by the harsh lockdown measures, but it also took much longer to recover. Whereas industrial production was back to normal in April, retail sales only reached pre-year levels in August 2020 – five months after the end of the national lockdown. In the end, retail sales in 2020 remained 4.8% lower than in 2019.

Even before the Covid-19 outbreak, China’s efforts to turn domestic consumption into the country’s main growth driver were stalling. At the beginning of the 2010s, total retail sales accounted for 36.9% of China’s GDP. The share increased in the first half of the decade, reaching 42.3% in 2016. Since then, however, retail sales have lost ground, dropping back to 2012 levels last year.

To reverse this trend, the Chinese government needs to tackle three deep-rooted problems: the rural-urban divide, low education levels, and rising household debt.

The rural-urban divide

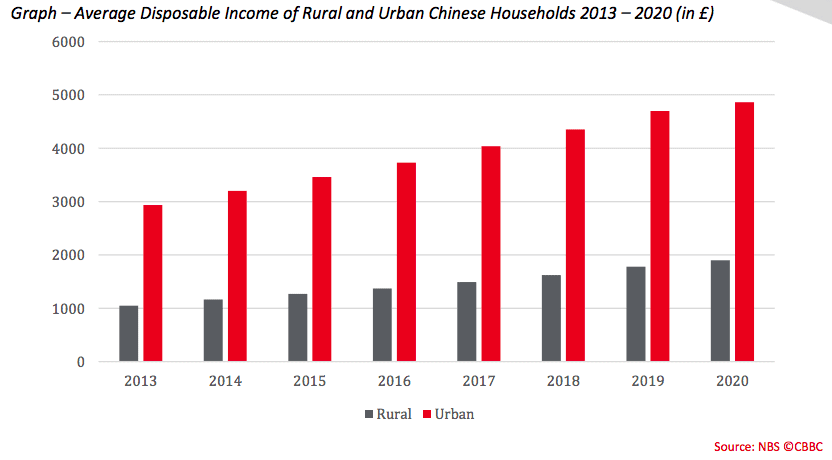

In 2020, the average disposable income of rural households was still 61% lower than that of urban households. As a result, the nearly 40% of Chinese people who are still living in rural areas account for only 22% of aggregate household consumption. Even though the gap has slightly narrowed over the last couple of years, the reduction in the discrepancy only came at a rate of 0.5 percentage points per year. At this rate, it would take over 120 years for rural households to catch up with their urban peers.

A simple way to increase the spending of rural Chinese would be to allow them to move to urban areas. Yet China’s restrictive household registration system – the hukou system – has barred many migrants from accessing urban welfare, education, and most importantly, real estate. Hukou reform has thus become a key element of the 14th Five-Year Plan. The Chinese government plans to remove all hukou restrictions for cities with less than 3 million registered residents, and lower barriers for municipalities with a population between 3 and 5 million people. Only six mega-cities – Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Chongqing, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen – would keep their restrictions in place.

In 2020, the average disposable income of rural households was still 61% lower than that of urban households. At the current rate, it would take over 120 years for rural households to catch up with their urban peers.

Education

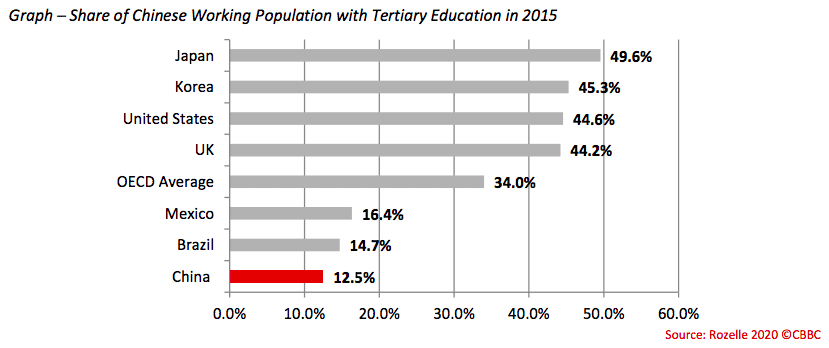

Although China is churning out nearly 9 million college graduates per year, the overall share of people with higher or even secondary education in the country’s workforce is surprisingly low. As the Stanford economist Scott Rozelle has pointed out in his recent book ‘Invisible China,’ only 12.5% of China’s working-age population had a tertiary education in 2015. This is not only far below the OECD average of 34% but even lower than the level in other developing countries like Mexico (16.4%) or Brazil (14.7%).

The 14th Five-Year Plan has set a target for the average working-age Chinese person to have 11.3 years of education. This is half a year longer than the current level of 10.8 years. Allowing more children with rural hukous to attend urban schools could be another way to improve educational levels. In 2015, only 30% of Chinese children had an urban hukou.

The Chinese government also wants to improve its vocational education sector. The number of vocational schools in China actually declined from over 14,400 in 2009 to around 10,000 in 2019. Many existing schools suffer from low enrolment and poor quality. In 2019, a vocational school in China’s northern province had to close after it was found to have issued ‘fake degrees’. Better supervision, standardisation and stricter quality control will therefore become more important.

Consumer debt

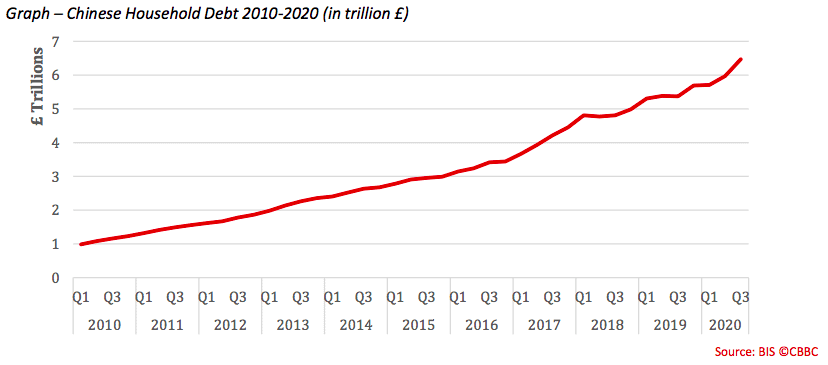

By the third quarter of 2020, Chinese household debt had reached £6.5 trillion, up from £5.7 trillion at the beginning of the year. China’s household debt-to-GDP ratio was 61.1%, according to data from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

While this ratio is still lower than that of many advanced economies – the UK’s ratio, for example, is 88.9% – younger middle-class Chinese are already changing consumer habits and are embracing second-hand goods. A McKinsey study from May 2020 also found that up to 30% of Chinese consumers would not return to pre-pandemic levels of consumption and continue to spend less. Yet reducing the household debt level won’t be easy, and will require caution and long-term strategies. For example, soaring real estate prices are a key driver of private debt but putting effective brakes on housing bubbles could easily backfire. A sharp drop in housing prices would lead to a wave of mortgage defaults, ruining the finances of many Chinese middle-class families. With the majority of private wealth now tied up in real estate, China is effectively locked in a vicious cycle in which rising real estate prices keep both lenders and borrowers solvent.

The CBBC view

The Chinese government is clearly aware of these challenges. Yet addressing them will require careful and potentially painful reforms.

Granting more Chinese access to an urban hukou is certainly the easiest way to address these problems. But even this will require more support for local governments, which, so far, have been reluctant to share scarce resources with non-registered residents. Opening schools, hospitals, and other municipal facilities to migrant workers could also trigger a backlash from local residents, who are often unwilling to share these resources with new entrants.

Improving education levels is more difficult, not least because it takes at least a decade to train an educated workforce. Relying on vocational training courses for older workers might provide a solution but will require better oversight and clear quality standards to ensure that graduates can compete in a high-income labour market.

Reducing household debt is the most difficult challenge. Ultimately, only when household income rises faster than expenditure – especially those for real estate – can China hope to keep private debt levels under control. This will require higher productivity levels and the creation of better-paying jobs. Unless this happens, household debt will continue to increase.

Click here to read the original analysis in full.