Will your company become the next H&M? Domestic brands are becoming more popular in China as Chinese consumers no longer presume that foreign goods are better than their domestic rivals and brands fall foul of nationalist rhetoric, writes Joe Cash. So, do Chinese consumers still want to buy British?

This question has become more pressing after leading Chinese e-commerce platforms began de-listing popular Western brands such as H&M last month. This came after the Communist Youth League unearthed a statement issued by the Swedish retailer a year earlier, stating that it wouldn’t source cotton from Xinjiang. Chinese netizens threatened to boycott H&M products, while its stores hurried to cover their shop signs. Is this evidence that Chinese consumers no longer want to buy from foreign brands, British ones included?

Thankfully for foreign companies trading in China, it’s not that simple. There is, as yet, no blanket preference for Chinese brands amongst local consumers; foreign brands are thriving here, too. But events in geo-politics are beginning to have a greater impact on consumer goods brands sold in the China market.

This phenomenon is part of a broader trend known in Chinese as guochao (国朝), which can be translated as ‘the rise of the national brands,’ and refers to a situation in which political or socio-economic undercurrents promote the rise of Chinese domestic brands.

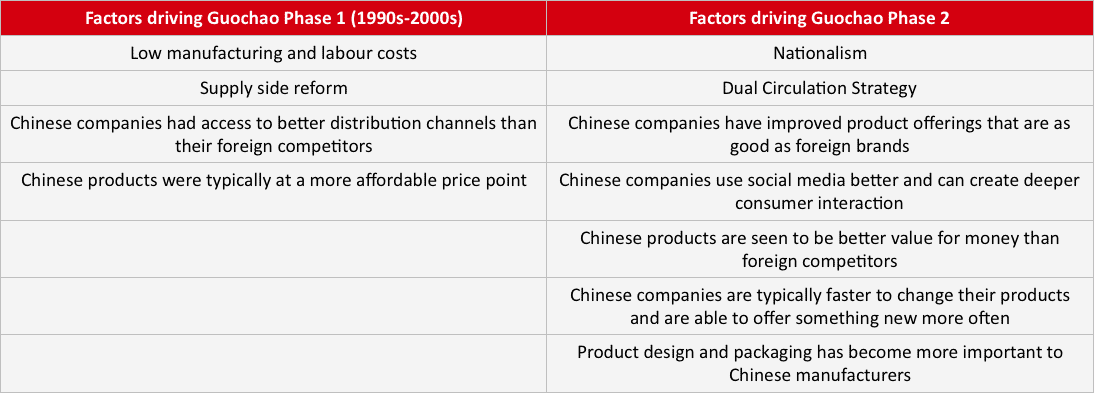

The last time guochao was a major issue for foreign companies selling into the China market was during the late 1990s and early 2000s. At that time, foreign companies were predominantly competing with socio-economic forces that were promoting the rise of Chinese brands; Chinese companies had access to cheap labour and could manufacture substitute goods at a fraction of the cost of their foreign rivals.

The new forces pushing guochao are far more complicated to navigate, with the two most pressing being millennial consumer preferences and rising nationalist sentiment. Foreign firms need to be particularly wary of these two factors because they can easily lead to a boycott of their goods, as Western brands have recently discovered the hard way. While there is a whole host of other factors pushing guochao, these are the only two with the potential to alienate foreign brands from the China market.

The sectors most susceptible to guochao

The sectors most susceptible to guochao are those in which China developed manufacturing capability during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Chinese companies successfully managed to reverse engineer products that they used to manufacture cheaply for foreign brands 20 years ago and are now launching their own versions that are often more innovative than the originals.

China’s millennials have cottoned on to this, and are increasingly likely to buy from Chinese brands as a result. Millennials also tend to have higher levels of disposable income than previous generations and are more inclined to believe in local manufacturing capabilities. To this generation, a product that is ‘Made in China’ isn’t cheap and tacky; rather, it is seen as likely to be cheaper because it is new and innovative.

China’s technology sector provides a good example. Whereas Chinese consumers used to flock to buy Apple iPhones bearing ‘Made in China, Designed in California’ stickers, they are now choosing to buy Huawei phones that were both designed and made in China. In 2015, Apple and Huawei held 14% of the smartphone market in China apiece, but today, Huawei enjoys 39% market share, while Apple holds just 8%.

To counter such risks, some foreign companies have acquired Chinese brands to front their sales into the local market, putting a barrier between their shareholders and Chinese consumers who might react negatively to broader political currents. A number of American breweries, for example, have acquired Chinese provincial beer brands, with US brands having become increasingly unpopular in the world’s largest beer market thanks to the political climate.

Sectors that appear less susceptible to guochao include the automobile, packaged food and beverages (particularly milk and products consumed by infants), and cosmetics industries. L’Oréal, Lancôme, Olay, and SKII remain the biggest selling cosmetic brands in China, for example.

Technological factors driving guochao

The role of Baidu and China’s e-commerce platforms in driving the guochao phenomenon cannot be overstated, thanks to the role the search engines and their algorithms play in directing consumers to products.

During guochao phase one, consumers were mainly influenced by a product’s price, packaging and analogue advertising when considering making a purchase. Now, products are predominantly advertised online on news sites or on pages maintained by key opinion leaders (KOLs).

KOLs and popular user responses on sites such as Xiaohongshu (Little Red Book) play a key role in driving Chinese consumers to buy, and make it far harder for foreign brands to control the environment for their product. Furthermore, millennials form the consumer group most likely to be engaging with content relating to politics and China’s tensions with the wider world. A full 63% of users searching for information around terms such as “trade war” are under 30 and otherwise browsing the internet and e-commerce platforms, according to Baidu. This is an unhelpful situation for foreign brands, considering that millennials also constitute the most active consumer group in China.

Does this mean that British brands are at a disadvantage when selling in China?

While there is no doubt that the guochao phenomenon has a powerful effect, Chinese and British brands alike are susceptible to falling foul of netizens. Chinese brands that aim to grab the attention of Chinese consumers by being overly reliant on being Chinese risk being perceived as clichéd or insincere too.

British brands can also take steps to appear more Chinese and benefit from the guochao wave. Using popular Chinese brand ambassadors or key opinion leaders (KOLs) to engage with the customer base is one example. A recent CBBC live-streamed session advertising British brands with Ji Jie – a popular KOL in Beijing – attracted an audience of 2.6 million.

UK companies could also take the further step of acquiring or rebranding an existing presence in the market as a Chinese brand. For example, Wusu, a popular Chinese lager branded originating from Xinjiang Province, is in fact owned by Carlsberg.

A UK Super Brand Day live stream with well-known KOL Ji Jie

Should British brands be worried about the Dual Circulation Strategy?

Guochao could mean that the ongoing trade tensions involving China and the promotion of the Dual Circulation Strategy make it less beneficial to be foreign branded when selling into China. This is because Chinese consumers are typically more driven by emotions when considering a purchase. This not only manifests itself in adherence to the opinions of KOLs, but also issues such as trade tensions and comments made by the Party on the country’s economic performance. The 14th Five-Year Plan sets out clearly how the Party expects China to become less reliant on foreign goods and services providers, and that manufacturing to meet domestic demand should be the priority. It is easy to see how Chinese consumers could misconstrue this messaging as “buy BYD rather than Mercedes Benz”, particularly if it is couched in anti-Western rhetoric stating that China is in a state of trade war.

The CBBC view

Chinese consumers still want to buy British, but consumers only prefer to buy foreign goods in certain sectors. In sectors where quality or safety are important, such as cosmetics, food and beverages for infants, and the automotive industry, foreign brands retain a significant lead in market share.

British brands should be mindful of the fact that Chinese companies learnt from the first phase of guochao, and have made great strides in terms of product quality, packaging and perception – the technology industry provides a good example.

Carlsberg’s acquisition of Wusu beer demonstrates that there are also instances where Chinese consumers want to buy foreign but don’t realise that they are doing so. China’s Wusu drinkers are not alone in this regard, there are lots of examples of Chinese brands that are famous for their quality but are owned by – and manufacture to the standards of – foreign brands.

Adaptability is the name of the game: As long as a brand can swiftly adapt to trends, they should be able to survive and thrive in China, regardless of brand origin. Click here to read the original analysis.

Want more insights like this? UK-China Consumer Week 2021 starts on April 19th and will shine a spotlight on opportunities for UK brands to re-engage with China. Find out more and sign up here.