David Law, Academic Director of Global Partnerships at Keele University, shares a touching story of commitment, courage and cross-cultural romance during the Second Sino-Japanese War

In recent years, I have discovered a story that I should have known long ago. I am now aiming to tell it whenever I have the chance. Recently, when in China, I gave two lectures to university audiences about Michael Lindsay. Under his Chinese name, Lin Maike, he is known as someone who made a major contribution to the war of resistance against the Japanese occupation.

Lindsay went to China to work at Yenching University, a missionary university in Beijing. But it was not the importation of tutorial teaching, Oxford style, that ensured his legacy. During 1938, it was possible, quite easily, to make contact with the forces fighting the Japanese occupation in Hebei Province. Aiming to investigate for himself, Michael took his bicycle by train from Beijing to Baoding. Then, with two companions, he rode into the countryside for a couple of miles and crossed the Japanese frontline with little difficulty. A mile later, he encountered Chinese sentries and was welcomed. He then worked with the Chinese Communist army for seven years.

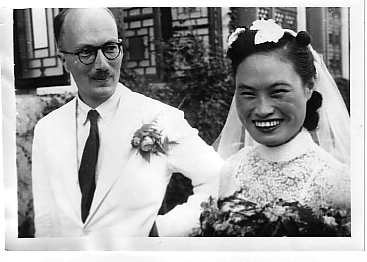

The sub-title of my lecture was “a story of commitment and courage”, and there was certainly plenty of both in play. It took courage for Michael to face the danger of working in occupied Beijing when he could easily have left China after a couple of years. This courage was matched by commitment, both to the anti-fascist struggle and also on a deeply personal level: Michael married a Chinese woman named Li Xiaoli (Hsiao Li) in 1941.

Michael’s study in a wing of the President’s house at Yenching University.

At Shanxi University in Taiyuan, I spoke to a group organised by the team responsible for international cooperation and exchange: around 30 young Chinese who were determined to improve their linguistic skills and regularly attend lectures in English. Taiyuan was a good place to deliver this lecture. Hsiao Li was from Shanxi Province and had attended high school in Taiyuan. She had involved herself in student protest, which led to her flight from the Shanxi capital.

In Shanghai, I presented to a very different group. At the National Accounting Institute, there was an audience of about 40 professionals, almost all from African countries and seconded from civil service posts. They were particularly attracted to the subject by the cross-cultural dimension.

I should have known the story because half my working life has been spent at Keele, the university founded by Michael’s father. Lindsay senior was both a distinguished academic leader at the University of Oxford for 20 years and a committed internationalist who stood as the Popular Front candidate in the Oxford by-election of 1938. By that time, Michael was in China, having travelled from Vancouver in late 1937. Dr Norman Bethune, the Canadian surgeon, was a passenger on the same boat. Bethune and Lindsay became friends, the former a committed communist and the latter a sceptic.

Like Dr Bethune, Michael is seen in China as a great example of international friendship. I initially came across Michael, lauded as “a true friend of China”, when I listened to President Xi’s London speech from 2015, given to an audience from both Houses of Parliament.

Michael wrote that he gave help “because it was clear that any thinking person had a duty to oppose the Japanese army”. He began by smuggling medicines and radio parts to the resistance forces. He imported a motorbike from Britain to travel around and, on occasion, his pillion passenger would be an activist who needed to make contact with the Communist underground in Beijing. During 1939 and 1940, Michael and Hsiao Li were developing a personal friendship based on political sympathy for the forces fighting against Japanese occupation. Both were inspired by concern for suffering rather than starting from a political manifesto. Being supporters of the anti-Japanese resistance movement took them close to the contemporary leaders of Chinese communism.

In the first hours after the news broke that Pearl Harbor had been bombed, Mr and Mrs Lindsay fled Yenching to avoid detention by the Kempeitai (Japanese military police) – the fate of almost all the staff at the university, including its president.

After driving about 50 miles from Beijing, the couple abandoned their car and walked to a safe area where the Chinese forces were in control. This took just over three weeks. They then made contact with the forces led by prominent military leader Nie Rongzhen.

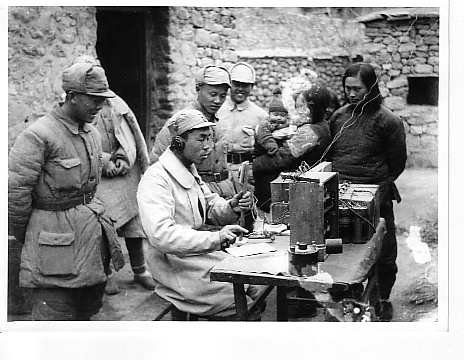

Michael had mainly taught Economics at Yenching University, but it was his skill with radio communications that was the greatest help to the guerrilla forces. Hsiao Li explained the trust that was placed in Michael: “Michael met many dedicated people at the radio station. … Luckily, he had brought a test meter and a slide rule with him. … The army trusted Michael completely … he had been helping them since 1938.”

In the Jinchaji base area in the Hebei/Shanxi borderlands, Michael worked with General Nie (who was later Mayor of Beijing and then ran the Chinese nuclear weapons programme) to establish a two-year academic programme in wireless communications. There were 26 in the class; many later achieved high distinction in science in the PRC. In addition, Michael gave practical training to wireless operators.

Hsiao Li watches local troops communicate by radio. In the centre is the head of the local radio department. The sets were designed and built by Lindsay using whatever parts were available. Ji Jian district, Central Hubei province

In September 1943, with the Lindsays living in the village of Zhongbaicha in Hebei Province, there was news of another offensive. “The radio department hid all its equipment and when the offensive started in the middle of the month, we moved into the high mountains.” Weeks became months, as the fugitives sought refuge in one place after another, and crossings were made between Hebei and Shanxi. In her autobiography, Bold Plum: With the Guerrillas in China’s War Against Japan, Hsiao Li gives one of the chapters the title ‘Staying One Step Ahead of the Japanese’.

Eventually, Hsiao Li and Michael walked for three months with their baby, Erica, to Yan’an, the capital of the communist-controlled area. Life in the Communist capital was very different from the base area of Jinchaji. Although the city had been bombed by Japanese planes, it was relatively safe by 1944, with more supplies and much better facilities.

Shortly after their arrival, the Lindsays were entertained by Chairman Mao Zedong with “a magnificent feast”. He praised their courage, but Michael wanted action: “With nothing to do I became restless … we were invited to lunch with General Zhu De … I then went to his study to discuss my work and I was appointed technical adviser to the Eighteenth Group Army communications department.”

As technical adviser, Michael was able to build the first equipment that allowed the Communist capital to transmit internationally. Michael also became involved in writing and editing news stories for the New China News Agency.

After the surrender of Japan in August 1945, there were offers to stay in China, but the parents were concerned for the safety of their young family (by now there were two children). Moreover, Michael had seen his work as part of the Allied war effort; with the war over, he sought a new role as a source of first-hand information about the reality of the conflict in China.

Zhou Enlai arranged for US$3000 to be given to the family to help with their repatriation. Mao Zedong and his wife, Jiang Qing, hosted a private dinner for the Lindsays two days before their departure from Yan’an in November 1945. After three weeks of travel, the Lindsay family was able to reach Oxford, where Lord and Lady Lindsay welcomed them.

Michael Lindsay went on to become a distinguished scholar, spending most of his academic life as Professor of Far Eastern Studies at the American University in Washington DC. He died in 1994. After this, Hsiao Li spent most of the rest of her life in China as a guest of the Chinese government. She passed away in 2010.

Photos reproduced from boldplum.com, the website of Hsiao Li Lindsay’s autobiography, Bold Plum: With the Guerrillas in China’s War Against Japan