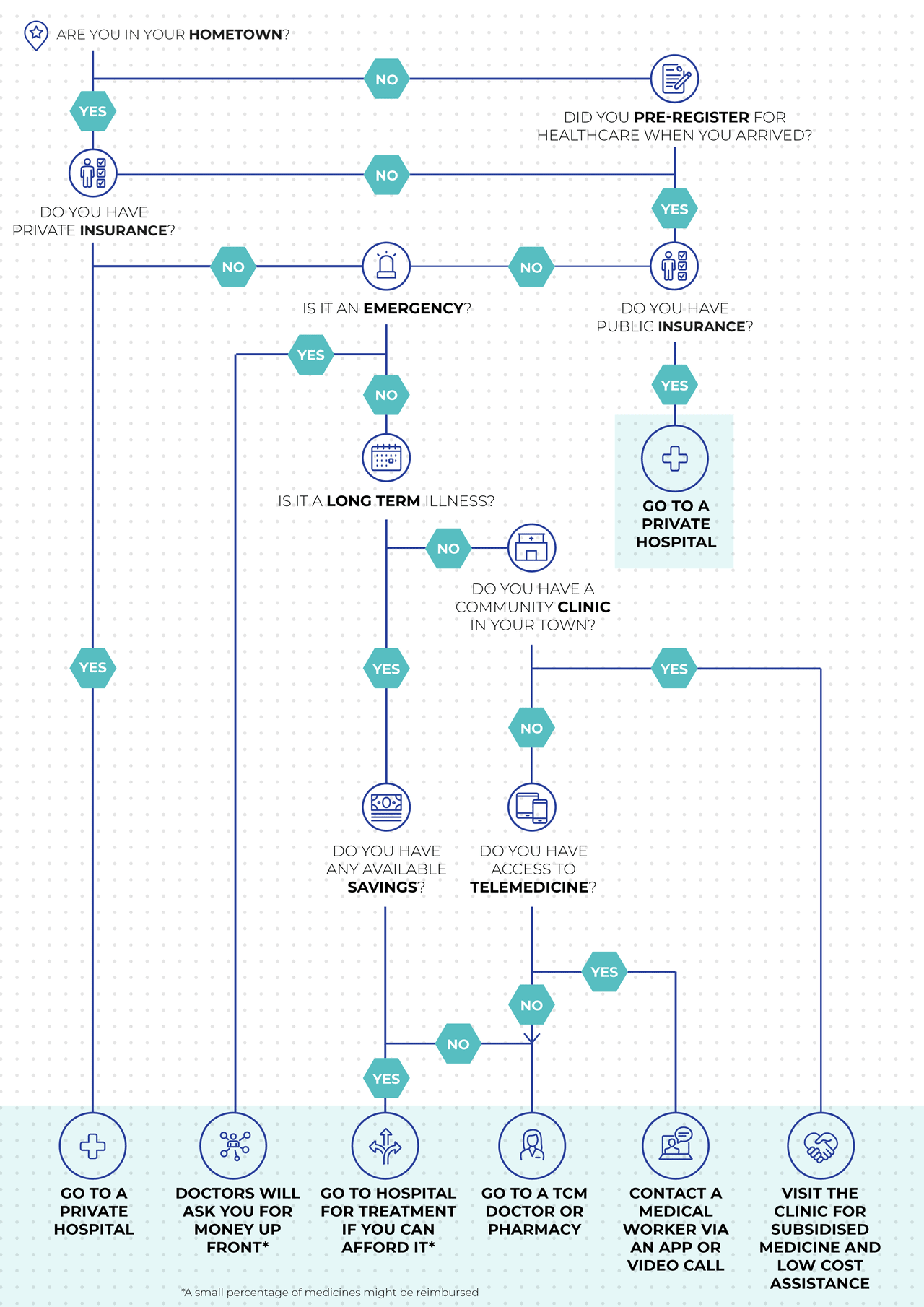

Getting healthcare in China can be complex, depending on employment, location, insurance-type and many other variables. Hai Feng of Peking University gives a comprehensive overview of how China’s healthcare system actually works

I am sick. What do I do?

Public insurance and steps toward universal healthcare

Approximately 95% of China’s population is covered by a public insurance programme. These are made up of voluntary public insurance and mandatory public insurances.

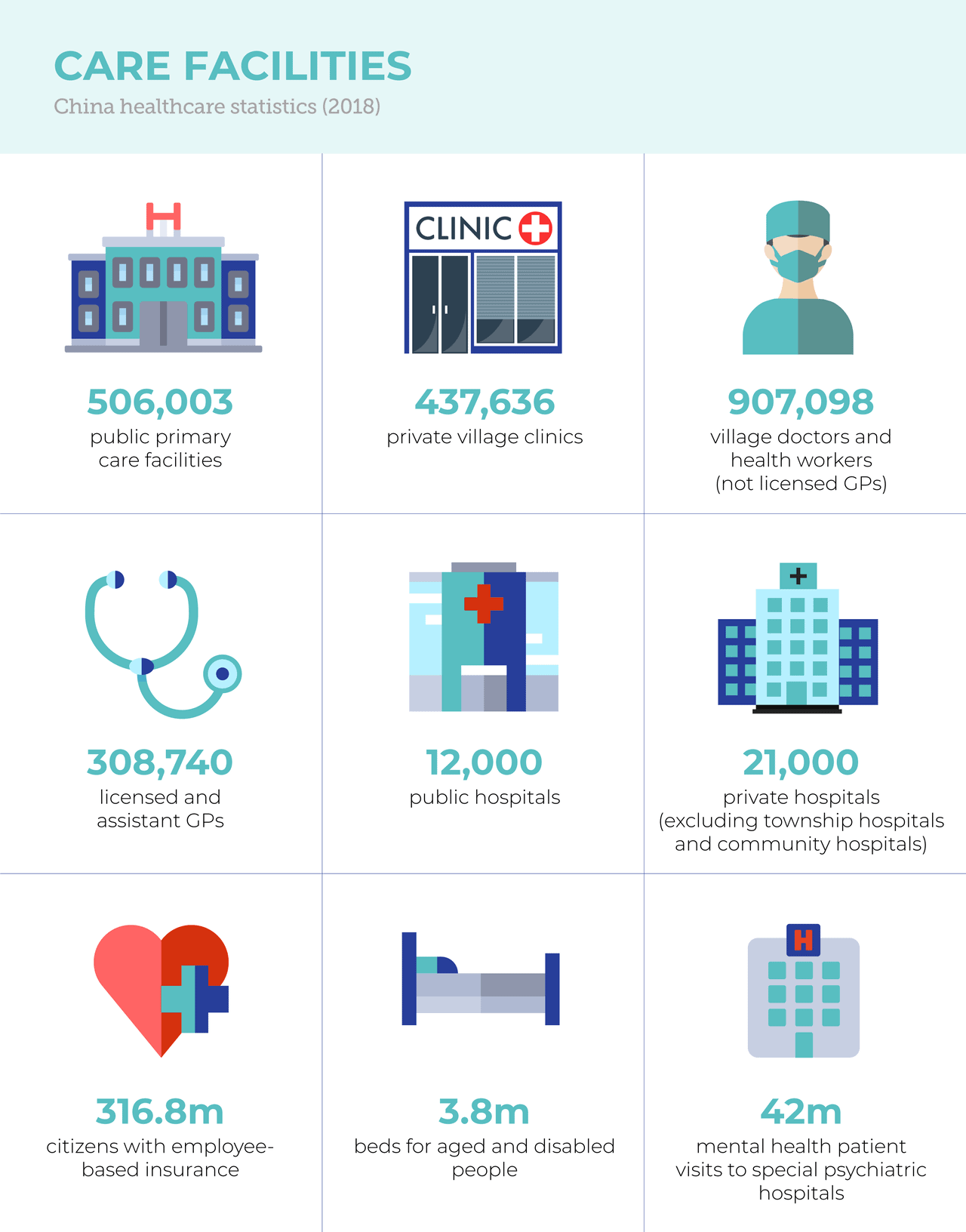

Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance is financed mainly from employee and employer payroll taxes, with minimal government funding. Participation is mandatory for workers in urban areas. In 2018, 316.8 million had employee-based insurance.

Urban-Rural Resident Basic Medical Insurance covers rural residents in addition to urban, self-employed individuals, children, students, elderly adults, and others. The insurance is voluntary at the household level.

In 2018, 897.4 million people were covered under one of these two insurance schemes. The Urban-Rural Resident Basic Medical Insurance is financed through annual fixed premiums, meaning individual premium contributions are minimal, and government subsidies for insurance premiums make up the majority of insurer revenues. In regions where the economy is less developed, the central government provides a much larger share of the subsidies than provincial and prefectural governments do. In more-developed provinces, most subsidies are locally provided (mainly by provincial governments).

Permanent foreign residents living in China are entitled to the same coverage benefits as citizens. However undocumented immigrants and visitors are not covered by publicly financed health insurance.

So what exactly is covered by public health insurance?

The benefits package in each case is defined by local governments, and therefore varies from province to province, and from city to city. But publicly-financed basic medical insurance typically covers:

- inpatient hospital care

- primary and specialist care

- prescription drugs

- mental health care

- physical therapy

- emergency care

- Traditional Chinese Medicine

A few dental services (such as tooth extraction, but not cleaning) and optometry services are also covered, but most are paid out-of-pocket. Home care and hospice care are often not included either. Durable medical equipment, such as wheelchairs and hearing aids, is also often not covered.

Preventive services, such as immunisation and disease screening, are included in a separate public-health benefit package funded by the central and local governments; every resident is entitled to these without copayments or deductibles.

Maternity care is covered by a separate insurance programme but is currently being merged into the basic medical insurance plan.

Cost-sharing, co-payments and reimbursements

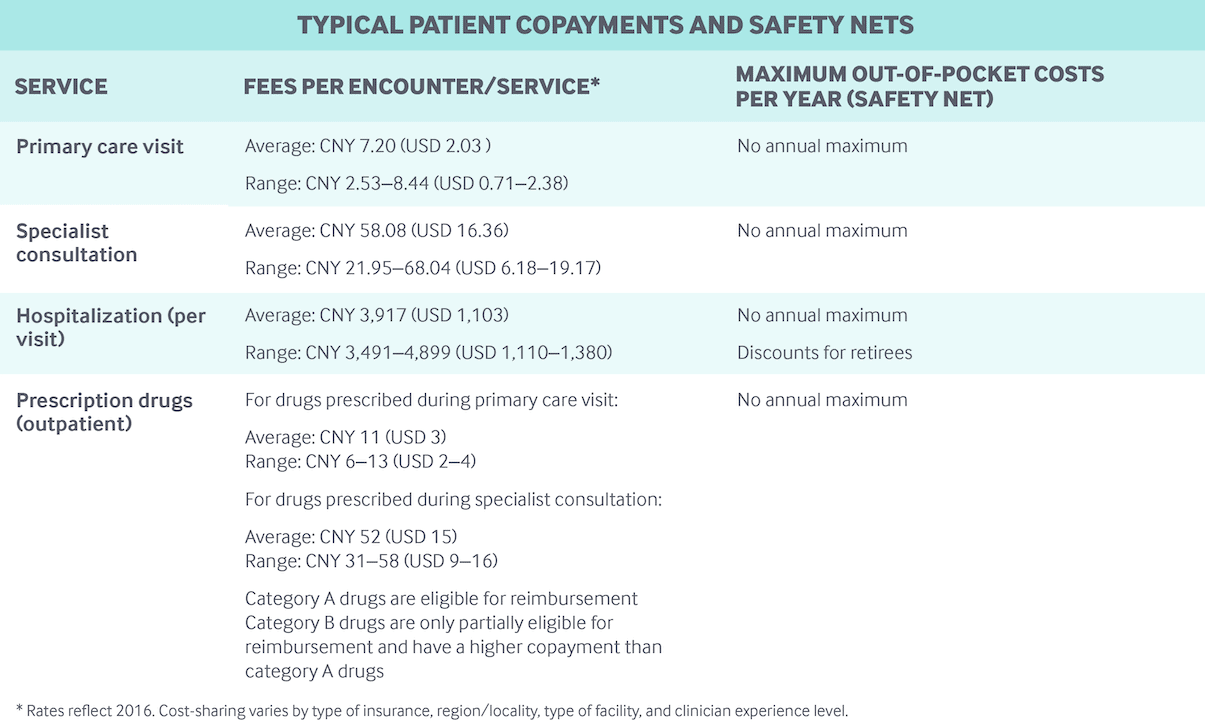

Inpatient and outpatient care, including prescription drugs, are subject to different deductibles, co-payments, and reimbursement ceilings depending on the insurance plan, region, type of hospital (community, secondary, or tertiary), and other factors:

- Co-payments for outpatient physician visits are often small (RMB 5–10), although physicians with professor titles have much higher co-payments.

- Prescription drug co-payments vary: in 2018 in Beijing, this was between 50% and 80% of the cost of the drug, depending on the hospital type.

- Co-payments for inpatient admissions are much higher than for outpatient services.

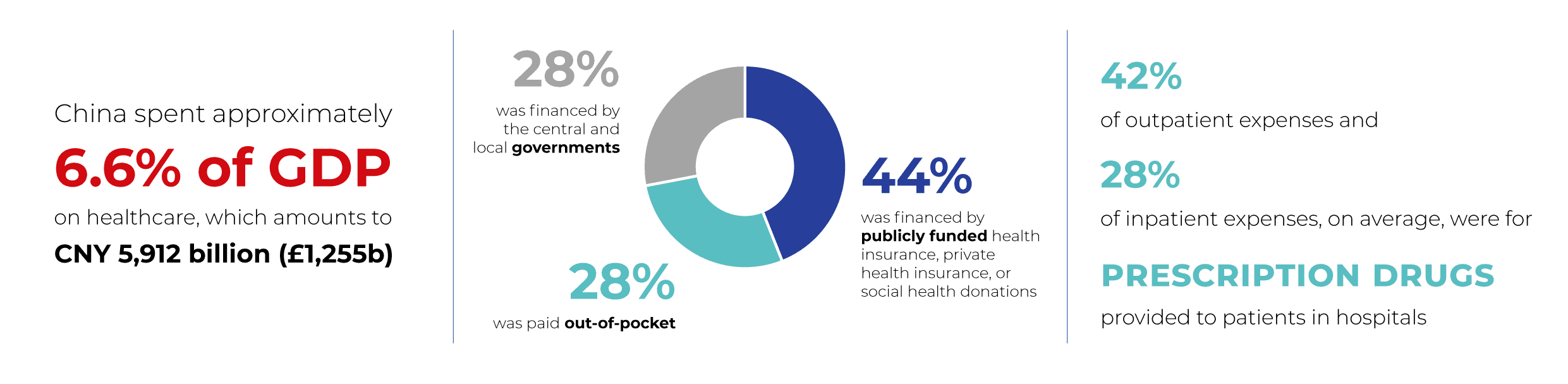

There are no annual caps on out-of-pocket spending. In 2018, out-of-pocket spending per capita was RMB 1,186 (£132) – representing about 28% of total health expenditures. A fairly high percentage of out-of-pocket spending goes on prescription drugs.

The public insurance programmes only reimburse patients up to a certain ceiling, above which residents must cover all out-of-pocket costs. Reimbursement ceilings are significantly lower for outpatient care than for inpatient care. For example, in 2018, the outpatient care ceiling was RMB 3,000 (£332) for Beijing residents with Urban-Rural Resident Basic Medical Insurance. In comparison, the ceiling for inpatient care was RMB 200,000 (£22,167). Annual deductibles have to be met before reimbursements, and different annual deductibles may apply for outpatient and inpatient care.

Preventive services, such as cancer screenings and flu vaccinations, are covered by a separate public health programme. Children and the elderly have no co-payments for these services, but other residents have to pay 100% of these services out-of-pocket.

People can use out-of-network health services (even across provinces), but these have higher co-payments.

Safety nets

For individuals who are not able to afford individual premiums for publicly-financed health insurance, or cannot cover out-of-pocket spending, a medical financial assistance programme – funded by local governments and social donations – serves as a safety net in both urban and rural areas.

The medical financial assistance programme prioritises catastrophic care expenses, with some coverage of emergency department costs and other expenses. Funds are used mainly to pay for individual deductibles, co-payments, and medical spending exceeding annual benefit caps, as well as individual premiums for publicly financed health insurance.

In 2018, 76.7 million people (approximately 5.5% of the population) received such assistance for health insurance enrolment, and 53.6 million people (3.8% of the population) received funds for direct health expenses.

How healthcare is provided

Primary care

Primary care is delivered primarily by:

- Village doctors and community health workers in rural clinics

- General practitioners (GPs) or family doctors in rural township and urban community hospitals

- Medical professionals (doctors and nurses) in secondary and tertiary hospitals.

In 2018, there were just 506,003 public primary care facilities and 437,636 private village clinics across China. Village doctors, who are not licensed GPs, can work only in village clinics. In 2018, there were 907,098 village doctors and health workers. Village clinics in rural areas receive technical support from township hospitals.

Patients are generally encouraged by local governments to seek care in village clinics, township hospitals or community hospitals, because cost-sharing is lower at these than at secondary or tertiary hospitals. However, residents can choose to see a GP in an upper-level hospital if they wish. Signing up with a GP in advance is not required, and referrals are generally not necessary to see outpatient specialists. There are few localities that use GPs as gatekeepers.

In 2018, China had 308,740 licensed and assistant GPs, representing 8.6% of all licensed physicians and assistant physicians. Unlike village doctors and health workers in the village clinics, GPs rarely work in solo or group practices; most are employed by hospitals and work with nurses and non-physician clinicians, who are also hospital employees.

Fees

Primary care in government-funded health institutions are regulated by local health authorities and the Bureaus of Commodity Prices. Primary care doctors in public hospitals and clinics cannot bill above the fee schedule. To encourage nongovernmental investment in health care, China began allowing non-public clinics and hospitals to charge above the fee schedule in 2014.

Village doctors and health workers in village clinics earn income through reimbursements for clinical services and public health services such as immunisations and chronic disease screening; and government subsidies are also available. Incomes vary substantially by region. GPs working at hospitals receive a base salary along with activity-based payments, such as patient registration fees. With fee-for-service still the dominant payment mechanism for hospitals (see below), hospital-based physicians have strong financial incentives to induce demand. It is estimated that wages constitute only one-quarter of physician incomes; the rest is thought to be derived from practice activities. No official income statistics are reported for doctors.

With fee-for-service still the dominant payment mechanism for hospitals (see below), hospital-based physicians have strong financial incentives to induce demand.

In 2018, 42% of outpatient expenses and 28% of inpatient expenses, on average, were for prescription drugs provided to patients in hospitals.

Hospitals:

Hospitals can be public or private, non-profit or for-profit. Most township hospitals and community hospitals are public, but both public and private secondary and tertiary hospitals exist in urban areas.

Rural township hospitals and urban community hospitals are often regarded as primary care facilities, more like village clinics than actual hospitals.

In 2018, there were approximately 12,000 public hospitals and 21,000 private hospitals (excluding township hospitals and community hospitals), of which about 20,500 were non-profit and 12,600 were for-profit.

Hospitals are paid through a combination of out-of-pocket payments, health insurance compensation, and, in the case of public hospitals, government subsidies. These subsidies represented 8.5% of total revenue in 2018.

Mental health services

Both outpatient and inpatient mental health services are covered by both public health insurance programs (Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance and Urban-Rural Resident Basic Medical Insurance). In 2018, there were 42 million mental health patient visits to special psychiatric hospitals; and on average, one psychiatrist treated 4.7 patients per day.

Long-term care and social support

Long-term care and social support are not a part of China’s public health insurance schemes. In accordance with Chinese tradition, long-term care is provided mainly by family members at home. There are very few formal long-term care providers, although private providers (some of them international entities) are entering the market, with services aimed at middle-class and wealthy families. Family caregivers are not entitled to financial support or tax benefits, and long-term care insurance is virtually non-existent; expenses for care in the few existing long-term care facilities are paid almost entirely out-of-pocket.

In accordance with Chinese tradition, long-term care is provided mainly by family members at home.

Governments encourage the integration of long-term care with other health care services, particularly those funded by private investment. There were 3.8 million beds available for elderly and disabled people in 2016.

Some hospice care is available, but it is normally not covered by health insurance.

Private health insurance

Purchased primarily by higher-income individuals and by employers for their workers, private insurance can be used to cover deductibles, co-payments, and other cost-sharing, as well as to provide coverage for expensive services not paid for by public insurance.

The total value of private health insurance premiums grew by 28.9% per year between 2010 and 2015. In 2015, private health insurance premiums accounted for 5.9% of total health expenditure. The Chinese government is encouraging development of the private insurance market, and some foreign insurance companies have recently entered the market as well.

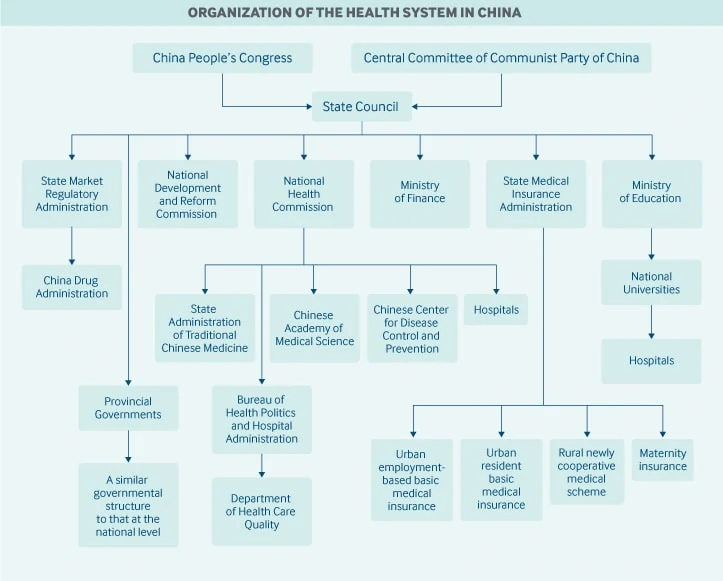

Main government bodies

The National Health Commission is the main national health agency in China. The commission formulates national health policies; coordinates and advances medical and healthcare reform; and supervises and administers public health, medical care, health emergency responses, and family planning services. The State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine is affiliated with the agency also.

The State Medical Insurance Administration oversees the basic medical insurance programmes, catastrophic medical insurance, a maternity insurance programme, the pricing of pharmaceutical products and health services, and a medical financial assistance programme.

The National People’s Congress is responsible for health legislation. However, major health policies and reforms may be initiated by the State Council and the Central Committee of the Communist Party, and these are regarded as law.

The National Development and Reform Commission oversees health infrastructure plans and competition among health care providers.

The Ministry of Finance provides funding for government health subsidies, health insurance contributions, and health system infrastructure.

The newly created State Market Regulatory Administration includes the China Drug Administration, which is responsible for drug approvals and licenses.

The China Center for Disease Control and Prevention, although not a government agency, is administrated by the National Health Commission.

The Chinese Academy of Medical Science, under the National Health Commission, is the national centre for health research.

Spending

In 2018, China spent approximately 6.6% of GDP on health care, which amounts to RMB 5,912 billion (USD 1,665 billion). Twenty-eight percent was financed by the central and local governments, 44% was financed by publicly funded health insurance, private health insurance, or social health donations, and 28% was paid out-of-pocket.

This report was commissioned and first published by the Commonwealth Fund. More information can be found at its website To learn more about China’s healthcare system contact CBBC‘s healthcare lead wendy.wang@cbbc.org.cn for more information.