China’s swine fever has reshaped global meat markets, writes Charlotte Middlehurst

When the first case of African Swine Fever (ASF) was reported in China fifteen months ago, its devastating impact on the global meat sector and the ripple effect on trade were unimaginable.

What began as a few cases of a rare and fatal pig virus at the Russian border has become a national emergency, labelled by the World Organisation for Animal Health as “the biggest threat of our generation to commercial livestock.”

The incurable virus, deadly to pigs but harmless to people, has spread to all of China’s 26 provinces resulting in the death of almost half of its pig population, either directly or through mass culls that have been both ordered by the authorities and undertaken voluntarily by desperate and fearful farmers.

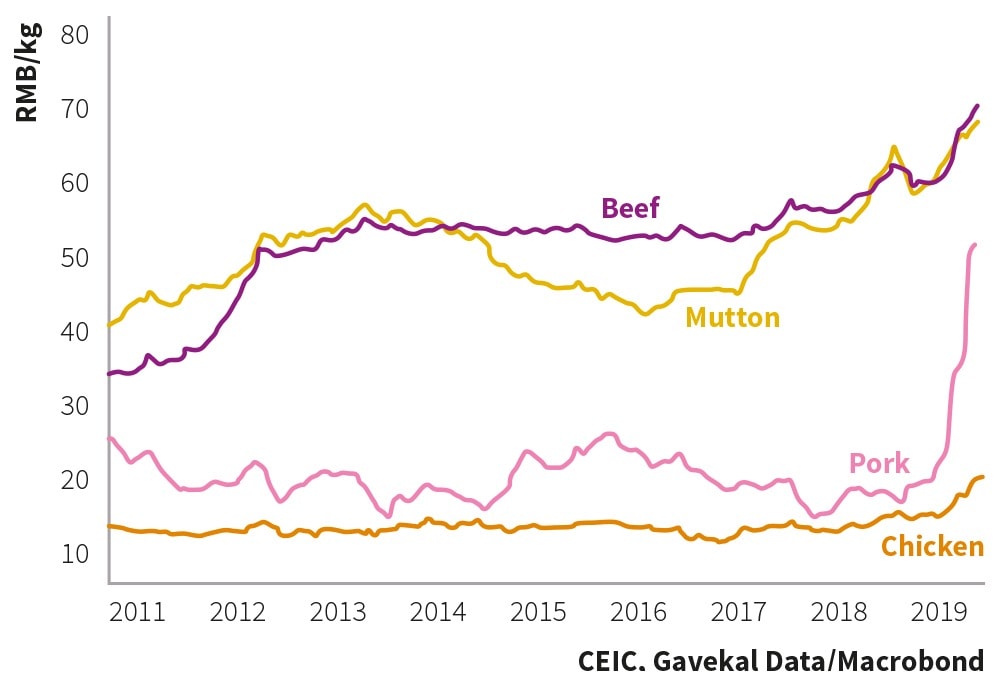

In just a short time, ASF has dealt a heavy blow that has left the industry convulsing. China’s pig herd has collapsed by 40 percent while its year on year pork prices had risen by 70 percent in September, according to the National Bureau of Statistics.

For Chinese farmers, the impact has been devastating. Backyard small-holdings with poor bio-security protection and little means to buffer against the shocks have been hit hardest, resulting in a loss of livelihood for thousands of communities. Beijing has tried to alleviate economic suffering by forcing state banks to step in and issue credit to affected farmers but this has been met with resistance. Travel bans, shutting down food markets and other responses have all failed to stop the spread.

The fate of China’s pigs has become a concern for people everywhere. Markets are waking up to the trade and economic implications — before ASF, China supplied half the world’s pig trade. Dwindling pork stocks have squeezed the global supply of meat dramatically. In Europe, soaring meat price inflation is driving up the cost of ham in Spain, Germany and Poland.

This has led to an uptick in beef and chicken supplies as farmers rush to fill the protein gap. But this will not make up for the loss in herd numbers. While production could stabilise by the end of next year it could take more than a decade for the disease to be fully under control, say experts.

Markets are waking up to the trade and economic implications — before African Swine Flu, China supplied half the world’s pig trade

“It’s the worst supply shock that China has ever suffered due to a disease,” says China consumer analyst Ernan Cui at Gavekal Dragonomics. “Supply has been falling faster than many people expected with the trend forecast to worsen. Pork prices are the highest they have ever been.”

Chinese officials calculate the pork shortfall to be 10 million tonnes whilst some independent analysts put the figure closer to 18 million. Meanwhile, pork prices are currently over 50RMB per kg wholesale. Before the outbreak, the average was 20RMB per kg. “Breaking 30 is very rare,” says Cui.

But not everyone is losing amid the soaring prices. Many provinces have been left with no choice but to import meat. Beijing has imposed a 72 per cent tariff on US pork in retaliation to President Trump’s trade war, allowing Brazil and Europe to make hay while the sun shines. Beijing has doubled the number of beef plants that have permits to sell directly to the mainland with imports expected to rise even further next year, according to Brazilian meat trade groups.

Meanwhile, Spain has increased the value of its sales to China by 90 percent (to £378 million) in the first six months of 2019, according to Interporc. It is also a boon for South American growers of soy and grain, used to making pig feed. But bad news for the planet as Brazil’s right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro ploughs on with controversial plans to open vast tracts of the Amazon to agricultural interests.

ASF is also threatening to become a political hot potato for China’s government. Ahead of the fanfare of the 70th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China on October 1, Hu Chunhua, Chinese Vice Premier and member of the Politburo told top officials that increasing pork production is a “major political task” for the Party. But reports that the government has suppressed information about the spread of the virus have raised questions about the effectiveness of its response.

Steps have been taken to try and rebuild the shattered industry, such as introducing the “green passage policy” – toll-free travel for certain categories of livestock; and generous subsidies for companies to build new infrastructure.

Meanwhile, some environmentalists even see this as an opportunity for China to embrace non-meat alternatives. But without a way of stopping the virus it is hard to see how China can continue to bring home the bacon.