A new exhibition at the British Museum encompasses China’s transformation as it suffered through two Opium Wars, the colonial occupation of Hong Kong, a disastrous war with Japan and more – and yet it was also when the country began opening up to the outside world. Paul French went along to find out more

The current blockbuster British Museum exhibition, China’s Hidden Century (1796-1912), runs till 8 October. For anyone with even the slightest interest in Chinese history, it’s a must, and indeed the numbers filing through the galleries indicate there’s a healthy appetite for the topic among Londoners and visitors to the city this summer. But what insights might those engaged in the often fraught and tricky world of doing business with China gain from the exhibition?

First off, the exhibition title. For those who know their Chinese history, the 19th century stretches from the elevation of the Jiaqing Emperor through to the fall of the 267-year-old dynasty and the establishment of the Chinese Republic in 1912. But those two seminal events, and all that came between – two Opium Wars, the colonial occupation of Hong Kong and the treaty port system, a 15-year-long civil war with the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, a disastrous war with Japan, the Boxer Uprising, the reign of the Empress Dowager, and finally the Xinhai Revolution – are, by and large, not taught in UK schools. So, it’s a “hidden century” to the British, if not to the Chinese themselves.

The exhibition tells multiple stories of that long century for China. It was often one of waning prestige, military defeat, foreign interference and disruption, bringing hard times for many. But it was also a period of innovation and new technology, an encroaching modernity and, amid the negative interactions with the outside world, a time of cultural and technological transfer, too. There’s no avoiding Britain’s role in these processes. The single exhibit that has perhaps excited most interest among Chinese visitors features two pages, embossed with a black wax seal, the red chops of the emperor, and the signature of the British plenipotentiary in China, Henry Pottinger. This is the actual Treaty of Nanking, signed on board HMS Cornwallis on 29 August 1842, at the conclusion of the First Opium War which, among other onerous conditions, ceded control of the island of Hong Kong to the British for 155 years until 1997.

Britain’s role in the Opium Wars and its imperialist designs for China, including its imposition of extraterritoriality on treaty ports such as Shanghai, cannot be overlooked. These are historical truths and have long been and will remain a sore point in relations. Yet this is also a period when the business so many UK firms and individuals do with China today commences. It is the story of our commercial contact with China and of China’s with the outside world.

China’s Hidden Century aims to tell the big story of the Qing empire, its resistance to foes, both internal and external, its palace intrigues, and its battles for survival in a weakened and threatened position. But it is also the story of China’s multitudinous population, from its growing metropolises to its rural countryside to those who chose to leave to go overseas to make their fortunes or gain an education. It is the story of how modern innovation and technologies – from vibrant clothes dyes to iron-clad gunboats, from railways to photography – encroached on the lives and businesses of every Chinese person.

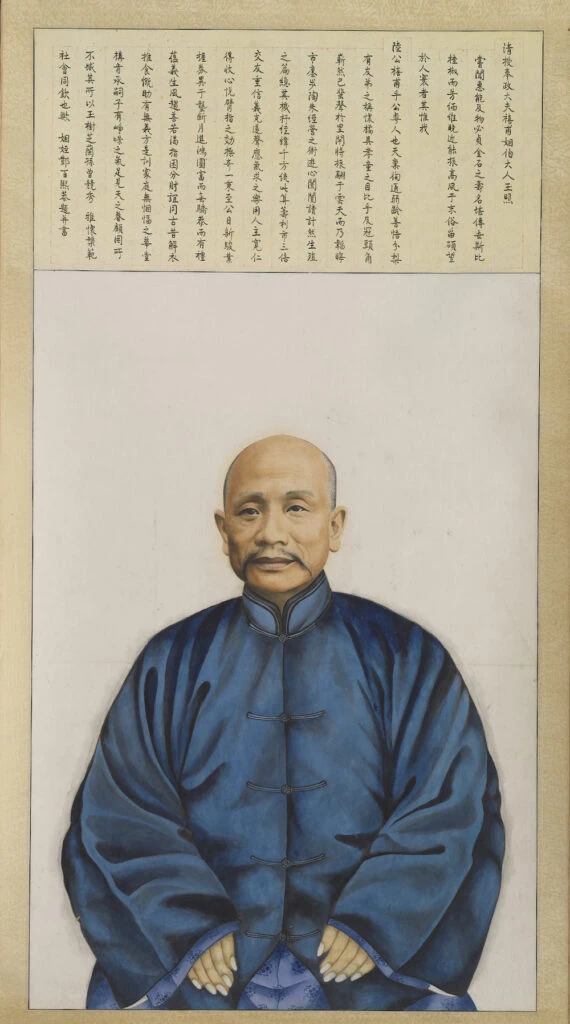

Take the emblematic poster for the exhibition (see first image in this article) – now to be seen on every tube station platform, bus shelter and billboard in London. It is a portrait of Lady Li, the wife of a successful Guangzhou businessman, Lu Xifu, painted around 1876. She appears stoical yet resolute, gazing directly at us across a century and a half. But the portrait is also stunningly realistic, the product of an artist (sadly anonymous) faced with the innovation of photography and its ability to capture real life. This is the very advent of the modern in Chinese life, and everything will change around Lady Li – from artistic styles to the city she inhabits as it expands rapidly over the course of her lifetime.

Portrait of Lu Xifu by unidentified artist, about 1876. Gift of Mr. Harp Ming Luk. With permission of Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada © ROM

Throughout the exhibition, we see the growth of the structural elements that anchor foreign business in China today: the initial growth of the Chinese rail system and logistics, the first engineering works and shipyards to encourage manufacturing, a modern banking system to support commerce and growth emerging, and a burgeoning Chinese business class looking to the world for ideas and inspiration, keen to establish their own domestic enterprises.

And ideas did enter China – from steamships to ply the coast, combustion engines to test China’s new roads, through to modern pharmaceuticals and stock markets. Despite internal disruption and foreign interference – beyond European imperialism, the disastrous 1894/1895 Sino-Japanese War presaged half a century of constant Japanese interference in Shandong, Manchuria and eventually all-out war – business did blossom and often flourish. Relationships were forged, and import and export markets were carved out.

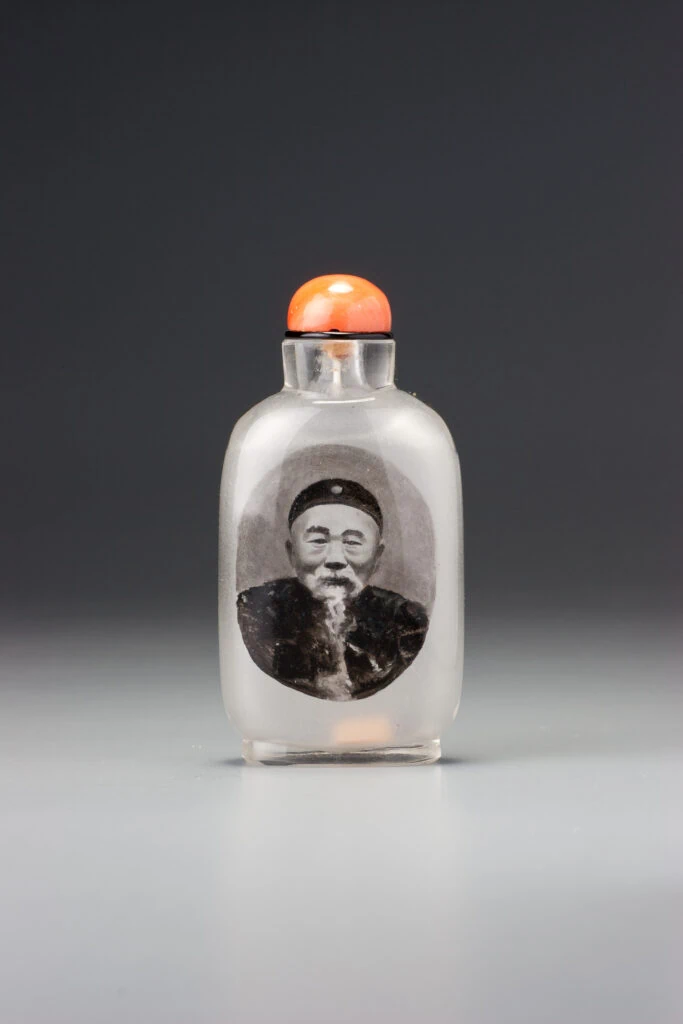

Items for export are included in the exhibition – carved jade from Peking workshops, “Tientsin” rugs, ceramics from the dragon kilns at Jingdezhen, and the once prolific silverware from Guangzhou and Shanghai that made so many of the punch bowls and silver goblets for wealthy European and American dinner tables. Technological innovations rapidly adopted for local consumer product use are also on display, including a snuff bottle decorated with an almost photographic likeness of the Confucian statesman and Qing diplomat Li Hongzhang.

Li Hongzhang is perhaps the exhibition thread that most determines 19th-century China’s business and commercial development. A skilled negotiator, the suppressor of the Taiping Rebellion, and the founder of China’s first modern military academies, he is also a key figure in the so-called “Self-Strengthening Movement” that runs through this entire hidden century. The effects of this movement included treaties to regulate trade between China and the West, a modern customs system, taxation of foreign business, a serious study of new technology and (in a very contemporary move) the start of governmental assistance to Chinese entrepreneurs engaged in competition against foreign enterprise.

Snuff bottle with image of Li Hongzhang (1823–1901), Beijing, 1900-1910. © Water, Pine and Stone Retreat Collection. Photographed by Nick Moss

In 1865, Li created a “general bureau of machinery production”, ushering in domestic telegraph companies, shipyards, railway concerns, textile mills, printing works and manufacturers of everyday products. Li did much to foster a commercial milieu, a semblance of industrial policy and manufacturing industries still recognisable today.

We can also see the material culture of these developments in the exhibition, such as banknotes printed with cargo ships, factories and city streets, examples of bonds issued by the Qing state for the building of new railways and advertising for modern pharmaceuticals. All these developments led to expanded cities, better road and rail networks and modern ports – the very essential sinews of internal and external trade.

Perhaps ultimately, it was this very desire to “self-strengthen”, to place the modern alongside the traditional, that inaugurated the end of the long 19th century. It initiated the demise of the 267-year-old Qing Dynasty and the creation, after the establishment of the first Chinese republic, of the China we interact with today.

The China of the early years of the “hidden century” – the early 1800s – was one that would undergo dramatic change. The Guangzhou Lady Li was born into was a walled one of low-level housing and pagodas. By the time she sat for her portrait, it was to become a major international port, a bustling, ever-expanding city of commerce and trade. Tarmacadam roads were coming, railway tracks were soon to be laid and a grand station was to be built connecting directly to Hankow and Hong Kong. As she sat for the artist, anti-Qing rebellions that slightly predated the successful 1911 revolution were occurring around her. The change she must have witnessed was enormous – essentially a move from a China we now find hard to recognise and historically touch to one we can still regularly find traces of today and that still impacts our businesses and interactions.