Is Didi Chuxing’s IPO in jeopardy because of poor conditions for its drivers? What of China’s army of delivery drivers who are also protesting over fair pay and working conditions? One thing is certain: the Chinese government is starting to take gig workers’ rights seriously, writes Torsten Weller

The outbreak of Covid-19 and the ensuing lockdown and social distancing rules turned China’s army of delivery drivers into a crucial lifeline for some people who were literally welded inside their homes. Additionally, e-commerce and online delivery platforms offered much-needed employment for millions of workers who suddenly found themselves without a job. Between January and March 2020, Meituan alone recruited 458,000 new drivers for its food delivery business.

Yet harsh working conditions and low payment also fuelled growing discontent, especially as many of the mostly young gig workers felt a lack of recognition for their essential role during the pandemic. Thus, starting last year, China saw a series of labour protests and grassroots-level movements driven by demand for higher pay and better job conditions. In one extreme case, in January 2021, a delivery driver who had worked for several Chinese food delivery companies set himself on fire in protest over unpaid wages.

While authorities initially reacted by arresting some of the organisers, policymakers also increased pressure on companies to ensure better pay and a safer work environment. In one instance, a deputy director of Beijing’s Bureau of Human Resources worked as a delivery driver live on TV, highlighting the low payment for a 12-hour shift.

Yet China’s underdeveloped labour law and the lack of a nationwide enforcement mechanism will make it difficult for Chinese authorities to address the problem. It is therefore likely that the government will increase pressure directly on China’s large online platforms to ensure that rules are followed across the country.

In one instance, a deputy director of Beijing’s Bureau of Human Resources worked as a delivery driver live on TV, highlighting the low payment for a 12-hour shift

Background

China’s gig economy is not as new as the English neologism suggests. One of China’s most famous novels, ‘Rickshaw Boy’ by Lao She, chronicles the travails of a rural youth called Xiangzi, who is trying to make a living working in the Beijing of the 1930s while pulling rickshaws.

After the revolution, rickshaws were banned and most urban gig workers were either sent back to the countryside or found jobs in urban factories. It was only after the end of the Maoist reforms and the beginning of Deng Xiaoping’s reforms that the gig economy made a comeback in China.

In particular, it was the rapid expansion of internet access and mobile payment apps that boosted the emergence of modern-day ‘rickshaw boys’ as online delivery and ride-hailing firms embraced the gig economy model of hiring drivers on short-term contracts rather than permanent employing them. Ele.Me, the Alibaba-backed online food delivery service platform, was founded in 2008. Didi Dache – which later merged with its rival to become today’s ride-hailing giant Didi Chuxing – came into existence in 2012.

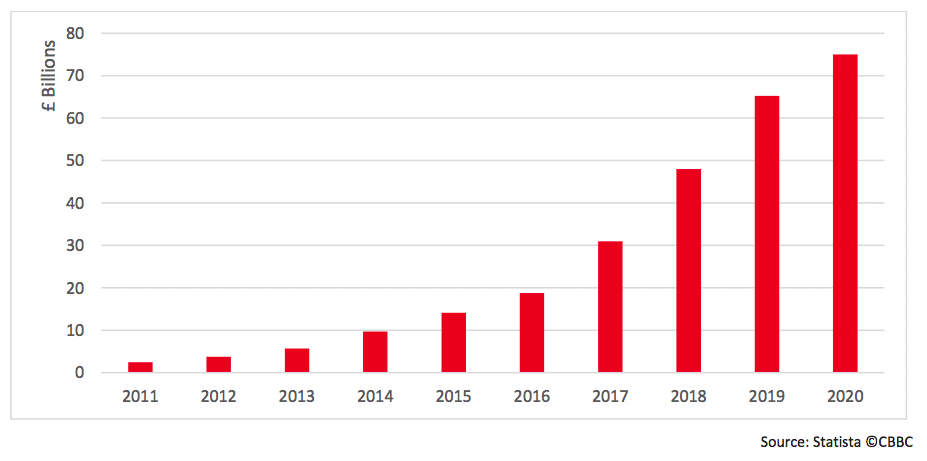

In the following years, the Chinese gig economy evolved into a multi-billion dollar business. The market size of food delivery services alone increased from £2.4 billion in 2011 to an estimated £75 billion last year. The market for ride-hailing, too, has reached similar proportions, with a value of over £50 billion in 2020, according to estimates by the international consultancy Bain.

Market side of the online food delivery business in China, 2011-2020

Who powers the gig economy?

Behind this phenomenal growth story stands a growing army of mostly young and male gig workers. The popularity of these new service platforms quickly led to a boom in China’s gig economy. Today, there are an estimated 7 million food delivery drivers in China. Indeed, some official figures estimate there are up to 200 million gig workers – roughly one-quarter of China’s entire labour force and equal to the population of Nigeria (Africa’s most populous nation).

Although China’s gig industry was initially an attractive way of earning some money before landing a more stable position, these jobs have morphed more and more into a fall-back option, which is chosen out of necessity and not as a springboard for socio-economic advancement.

One factor that has – somewhat predictably – contributed to the worsening situation is the increasing need for platforms to generate profit. Faced with fierce competition and inspired by Amazon’s business model of expansion at all costs, many online delivery and ride-hailing companies initially spend huge amounts of cash on discounts and premiums to gain market share, often burning billions of RMB in the process.

Meituan, which controls 65% of China’s food delivery market, booked over £200 million in losses last year despite a revenue increase of 35%. Even DiDi lost over £1.1 billion in 2020, according to data provided by the company to the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Yet pressure from investors and the companies’ plans to go public forced many to reduce payments to drivers.

Didi Chuxing, for example, increased its commission from drivers up to 50% of a ride’s fare, according to a recent report by China’s state media. Food delivery platforms also changed their payment algorithms, giving drivers less time to fulfil an order before incurring penalties. Based on a widely circulated report by the state-owned magazine Renwu (人物), the change not only made it harder for drivers to gain premiums, it also increased the risk of dangerous road accidents. The report quotes one study showing that the number of fatal road accidents involving delivery drivers increased significantly between 2017 and 2019.

Meituan delivery drivers wait for orders outside of a popular mall in Beijing

The rise in protests by gig workers

Research by the China Labour Bulletin, a Hong Kong-based NGO, found that labour activity has increased markedly over the last five years. In 2018 and 2019, food delivery drivers staged a total of 102 protests compared to only 19 in the two preceding years. Of all recorded protests since 2016, over 90% concerned low pay or wage arrears.

The pandemic put a preliminary halt to public protests. But for the Chinese government, more important than the number of strikes was the increasing level of labour organisation among gig workers. One organiser, Chen Guojian, had as much as 16,000 contacts via various WeChat groups. For a Communist government, such a level of labour mobilisation outside the Party has been viewed as problematic. In February 2021, police arrested Chen and charged him with “picking quarrels”, a generic crime that is punishable with up to five years in prison.

But the central government also recognised that the gig workers’ situation was untenable and that the sheer number of such workers could pose a serious risk for the country’s domestic stability – not least in the year marking the 100th anniversary of China’s Communist Party. Also, having a growing urban underclass of gig workers chimes ill with the government’s avowed goal – as outlined in its new Dual Circulation Strategy – of boosting domestic consumption and individual incomes.

Authorities are thus pursuing a two-pronged approach. On the one hand, they are cracking down on unauthorised protests and labour activism. On the other hand, they are embracing the drivers’ cause by increasing pressure on online platforms to raise wages and improve work safety.

In March last year, China’s government recognised – for the first time – delivery drivers as an independent profession. Earlier this year, DiDi, Meituan and eight other ride-hailing and online delivery firms were invited by a group of eight central regulators to discuss the working conditions of gig workers.

The meeting resembled a similar summons of China’s tech giants last year, heralding the beginning of a massive anti-trust campaign. Maybe unsurprisingly, Chinese regulators announced on 17 June that they would probe Didi Chuxing for monopolistic behaviour, thus threatening the company’s planned IPO.

But whether the increased scrutiny really benefits gig workers remains to be seen. The All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU) – China’s only legal representative body for workers – announced in August 2020 that it would intensify its efforts to improve the conditions of delivery drivers and other gig workers, yet so far little has come from this. A collective bargaining agreement signed by ACFTU’s Beijing branch with local express delivery firms in October 2020 has delivered little besides an ‘encouragement’ to pay better wages and social welfare contributions.

However, this doesn’t mean that Chinese authorities will sit idly by. Similar to China’s tech giants, the country’s gig economy has grown too big to ignore. It is, therefore, more likely that we will see increased pressure on local government – including labour courts – to enforce labour laws and put pressure on local branches of online platforms to ensure that wages are paid in time and safety regulations are fully complied with.

The CBBC View

The misgivings of China’s gig workers resemble in many regards those expressed by their peers in the West. Yet the fractured nature of both China’s labour bureaucracy and online platforms’ own internal division into franchises makes an effective solution to the problem much harder to find. This makes it difficult for the Chinese government to follow the examples of California or the UK, where recent court rulings ordered ride-hailing companies to ensure that their drivers receive fair salaries and social benefits.

Yet pressure on online platforms will undoubtedly grow. China’s Communist Party can’t afford to ignore a vast group of workers, who – unlike other professional groups – possesses a high degree of intra-professional and cross-provincial solidarity and organisational potential. It is, therefore, more likely that the Chinese government will try to force the country’s large ride-hailing and food delivery platforms to ensure that workers’ demands are met.

Although such policies will have only a limited impact on foreign businesses, few of which are relying on gig workers, it is nonetheless noteworthy that – once again – the Chinese government is targeting big tech firms as they are about to go public. Just like last year’s Ant Group case, the anti-trust investigation against DiDi Chuxing comes just days after the company filed for an IPO. The legal uncertainty over gig workers’ salaries and labour rights adds yet another difficulty for investors – including foreign ones – to price these company’s future prospects properly.