Gordon Orr is a non-executive board member of Meituan, Swire Pacific, Lenovo, EQT and the China-Britain Business Council. He is a senior advisor to McKinsey on China related topics and was responsible for establishing McKinsey’s China practice in the 1990s. Here, he provides his insights as to what might be in store for China in 2021

China enters 2021 economically stronger relative to major economies than anytime since 2009. This apparent strength creates extremely high expectations for China to deliver on its forecasted economic recovery, on its rollout of vaccines in China and beyond, and on stabilising its geopolitical relationships. In a year when avoiding major risks and sources of instability remain paramount, China’s leaders will find it harder to keep the economy on track than anticipated.

Overall

Economic growth expectations for 2021 of 8% plus (real RMB terms) are pricing in perfection. There is little upside beyond this number and much downside. Most critical is the need to accelerate still sluggish consumer spending. The recent pivot in government policy to demand stimulation reflects growing concern in Beijing that consumers are not stepping up their spending as needed.

China’s export strength in 2020 has resulted from global demand for PPE, a global shift to online purchasing, and Chinese manufacturers stepping up to fill gaps left by manufacturers locked down in other markets. In 2021, post-vaccine manufacturers outside of China will fully recover. Additionally, the secular trend to move manufacturing (especially destined for the US) out of China will restart, and China-based manufacturers will feel the full impact of the RMB’s appreciation.

Domestically, infrastructure spending has run its course, offering little upside. The continued flirtation with bankruptcy of several of China’s leading property developers highlights fragility in this sector. Expect aggressive action to lower tax and other burdens on individuals. Concerns about growth will also push Beijing towards opening up further to foreign capital and business participation within China. Negative lists will shorten further and more licenses will be issued from basic materials to financial services.

Expect aggressive action to lower tax and other burdens on individuals. Concerns about growth will also push Beijing towards opening up further to foreign capital and business participation within China

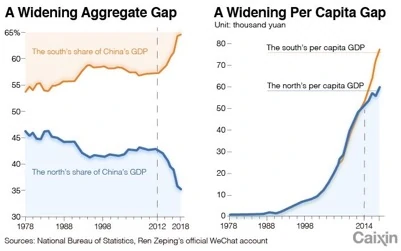

Geographically, China’s economic centre of gravity continued its long-term shift southwards in 2020, as Tianjin fell out of the 10 ten cities by GDP, leaving only Beijing from the north on the list. Beyond the usual clusters of the Pearl River and Yangtze River Deltas, President Xi continues to push for the development of the Hainan Free Trade Port (HFTP), with preferential policies for industries from aviation to health and internet services, beyond traditional support for tourism sectors.

If China does achieve 8% growth in 2021 – with domestic inflation of 1-2% and currency appreciation of 3-5% – then the size of China’s economy relative to the US could exceed 75% in 2021 (using IMF forecasts), an outcome only likely to increase the political pressure in the US to “do something about China”.

Consumers

Covid has forced Chinese consumers to think harder about their spending and seek higher quality products

The Covid economic shock, though short, was traumatic for many lower-income Chinese consumers. China’s younger generations had not experienced anything as close to a recession prior to Covid-19 in 2020. The virus has forced them to think harder about spending, saving, and trade-offs in purchasing behaviour. While aggregate savings have grown this year — McKinsey reported the country’s household deposit balance increased by 8% over the first quarter to reach 87.8 trillion RMB, this was concentrated in high-income households.

These consumers said they planned to increase sources of income through wealth management, investments and mutual funds. But these richer consumers at least still have savings. Many at lower income levels found their modest savings entirely wiped out by the Covid lockdown. Unsurprisingly, they have been both unable and unwilling to jump back to prior spending levels. And probably won’t until they are convinced that a vaccine has eliminated the risk of recurrence.

The virus has also led consumers to seek better quality and healthier options: More than 70% of respondents in the McKinsey Covid-19 consumer survey will continue to spend more time and money purchasing safe and eco-friendly products, while three-quarters want to eat more healthily after the crisis. But not all spending has shifted to the “virtuous”: high-end malls in China have seen their sales grow 25-35% verses 2019 as the wealthiest consumers, unable to travel, spent much more within China than before.

When Chinese consumers do spend, they are increasingly focused on strong local brands. In its BrandZ report, WPP showed a 30% increase in the value of the top 100 Chinese brands in 2020, almost all associated with their growing domestic success. Likewise, China Skinny research highlights the phenomenal success of local brands such as Yatsen in beauty.

Of course, prior trends will continue. Chinese consumers will be more digital than ever before, with the major online battles in 2021 being over who gets to deliver fresh groceries to the home and who provides the digital health care solutions that exploded in popularity during 2020.

Industry sectors

An emphasis on the semiconductor industry is part of China’s dual circulation strategy

The most attractive sectors for investment in 2021 will be shaped both by recovering consumer demand, and by government priorities set out in the 14th Five-Year Plan. The high-level outlines of the plan are clear – risk mitigation and stability, greater state involvement in business, focus on industries of the future (with a special emphasis on semiconductors), accelerating growth through consumption, and sustainable growth – all within the “dual circulation” logic.

The major online battles in 2021 (will be) over who gets to deliver fresh groceries to the home and who provides the digital health care solutions

Cross border trade flows will be impacted by priorities for both inbound and outbound goods.

Priority inbound sectors are those in which China wishes in the short term to ensure that it retains maximum access to global suppliers and in the medium term build up world-class domestic capabilities. Beyond semiconductors, particular priorities are Agriculture Tech and Biotech. AgriTech is not simply about providing a greater proportion of China’s food supply domestically. It is also about ensuring that food is grown from seeds where the IP is developed and owned in China.

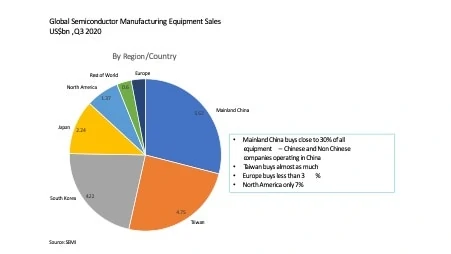

Traditional energy supplies – oil, gas and the key minerals used in new energy vehicles (NEV) batteries – remain priorities for ensuring stability. Even under the latest plans, renewables will only provide 25% of China’s energy by 2030, much of the remainder will still need to be imported. In semiconductors, mainland China buys more than one quarter of all manufacturing equipment sold today (compared with less than 3% in Europe) to go along with the billions of dollars being invested in semiconductor research and start-ups. That proportion could rise above 30% in 2021.

Priority outbound sectors are largely emerging industries, where China already feels confident in its potential to be world-class and in which it seeks to ensure maximum access to markets beyond China. China’s asks in the EU-China investment agreement are very much focused on this. In this category are sectors such as new energy vehicles, green tech and smart tech. Smart tech covers many subcategories, often 5G enabled, from smart cities to smart factories and industrial IoT. In these sectors, China will seek to export not only hardware as usual but also software, and critically, the standards on which the Chinese products are based. Chinese produced NEV exports will range from Teslas made in China for sale in Europe and Teslas emerging China-owned competitors such as Nio, Xpeng and LiAuto, to sub-US$10,000 entry-level EVs to EV buses from BYD.

Should the EU-China Investment agreement be ratified, European companies should receive preferential market access in a number of these sectors in China, and Chinese companies will be permitted to push forward on their green energy and NEV investment strategies into the EU. The impact will not be as material and swift as the opening up of the financial sector to majority foreign-owned players was in 2020, and the text has not yet been finalised, but openings are promised in NEVs, cloud services, financial services and health.

Online grocery shopping will be the most contested and contentious consumer-facing sector in China in 2021, highlighting both the further digitalisation of the Chinese consumer and more aggressive intervention by Chinese regulators. Community grocery buying, where one person organises grocery purchase and delivery for the following day for a community of typically 30 of their neighbours, is seen as the next major showdown between China’s internet giants (including Meituan, where I sit on the board).

Online grocery shopping will be the most contested and contentious consumer-facing sector in China in 2021

As with many online to offline business models, economies of scale at the city level are key to success. While being so popular with consumers that it could reach close to 20% of grocery sales by 2022, the sudden emergence of grocery e-commerce will receive push back because of the disruption to fragmented, less efficient traditional channels – distributors (often state-owned) and local retailers (hundreds of thousands of mom-and-pop outlets). Regulators will use their new anti-monopoly powers to ensure an orderly evolution of the market.

Regulation

Cyber security regulations and personal data protection laws will become stricter

2021 will be a year of intense regulatory action in China. In multiple areas, regulators are on the front foot with a common intent to centralise and standardise regulations (eliminating provincial variations in how regulations are applied) and to better protect individuals and small business from predatory behaviours by larger businesses. These policies are targeted at all businesses and of course, foreign businesses will come under scrutiny as a result. Key areas include:

· Anti-trust enforcement by SAMR will target discriminatory pricing, forced exclusivity, below cost pricing and acquisitions to pre-empt competition. Larger internet companies will find ways to adapt but some will see their margins impacted.

· The corporate social credit system will become more effective at joining the dots to highlight corporate bad actors as the system more effectively consolidates data already held on corporations across multiple (largely local) databases.

· Undercapitalised players in the financial sector will find they need to add billions of dollars in new capital requirements to sustain their existing business model and operators using a provincial license to operate nationwide will find that path no longer open. Sales of bank wealth management products will be restricted by new regulations on distribution, with third-party platforms removing many such products already in January.

· New rules on personal data protection pile on top of existing cybersecurity and national security requirements. Consumer tolerance of abuse of their personal data has fallen rapidly in recent years and the government is catching up. More explicit opt ins for collecting data, restrictions on selling data to third parties, government approvals for taking data cross-border and even higher requirements on protecting minors’ data will apply. Sensitive data still walks out the door of corporations, taken by low paid employees as was the case with YTO earlier this year. Corporations will be expected to have policies to prevent this, and effective implementation of the policy. Breaches or failures to comply must be self-reported or corporations will face additional liabilities.

· Technology exporters will need to navigate China’s new export control law, largely modelled on what China has seen applied by the US. Details of the law were laid out in December; many existing technology exporters are likely to find that they need additional licenses to exports in the future.

· Taking lessons from governments around the world, Beijing has rolled out a national security screening process as part of the approval process for foreign acquisition of companies based in China.

Vaccines

Vaccine production and procurement provide an insight into how China’s industries work

As of late December, China has inoculated several million high-risk workers (overseas travellers, military, health workers, police officers, firefighters, transport and logistics workers) under emergency regulatory approvals for vaccine use, while at least five vaccines developed in China progress through Phase 3 trials in a dozen countries worldwide. Government officials have claimed 600 million doses will be available by year end and that over 2 billion will be produced in 2021.

China’s development of Covid-19 vaccines is a microcosm of how many industries work in China:

· A major state-owned enterprise, Sinopharm, is the giant in the market. A Fortune 200 company with 100,000 employees and tens of manufacturing plants. In an ideal world, Beijing would like Sinopharm to be one of, if not the, “winner”.

· Competing with Sinopharm are multiple private sector competitors ranging from long-established local companies (including Sinovac, Wantai) to relatively recent start-ups led by returnees from overseas (including Cansino, Clover) – often with only a few hundred research focused employees. They will need third parties to help scale production.

· Government and university health institutes are partnering with corporate developers in public-private partnerships.

· Fosun pursued a different path, but one common to many other industries in China – buy abroad and bring back to China. Pharmaceuticals is just one leg for Fosun, which is one of the largest private conglomerates in China, internationally owning businesses such as ClubMed and the UK football club Wolverhampton Wanderers. Fosun looked abroad, invested in BioNTech, secured exclusive distribution rights in China for their vaccine, and has now imported the first units.

· These companies are listed across the world on exchanges in Shanghai, Shenzhen, Hong Kong and New York.

· Vaccine technologies being worked on span the traditional to the leading edge, including 1) inactivated virus; 2) protein-based vaccine; 3) viral vector; and 4) mRNA/DNA.

· At least two vaccine developers have links to the Chinese military.

The government will have to overcome some natural concerns about vaccines in China, given the industry’s poor track record of quality control. Expired polio shots, unsafe rabies vaccine and unsafe DPT vaccine incidents have all occurred in the past five years. Vaccination will be encouraged by requiring it for travel on trains and planes and entry to public buildings and by making vaccination free to consumers.

Despite these positive developments, China’s borders are unlikely to open wide quickly. Government officials will be conservative. Health-based reasoning could also get intertwined with geopolitics to leave potential travellers from specific countries at the back of the line for getting quarantine-free entry into China in 2021.

Hong Kong

Hong Kong will play a major role in the financial sector as mainland companies increasingly dominate

Entering 2021, Hong Kong remains China’s international financial centre, and through the narrow lens of that sector, had a surprisingly successful 2020 with IPOs continuing throughout the year, demonstrating that much of the sector’s activity can flourish even when arrivals at the airport fall to less than 1% of normal levels.

A personal milestone came when the Hang Seng Index adjusted the companies it includes to take out Swire Pacific (a member since the index was launched 51 years ago) and bring in Meituan, listed only two years ago. (I am a board member of both companies). Weighted by value, mainland companies now make up over 60% over the index. With the pressure to delist Chinese companies from the US only growing, underlying momentum supporting the financial market in 2021 remains strong.

With Hong Kong now on Wave four of the virus, there seems little likelihood that international business travel will return at any scale into Hong Kong until the second half of 2021. As a result, many business decisions remain on hold – whether to adjust the scale of operations in Hong Kong, whether to move activity into mainland China or elsewhere in Asia and the like. When the border with mainland China reopens, expect a step up in investment from mainland China in Hong Kong, of mainland companies expanding their operations in Hong Kong and mainland talent moving to Hong Kong. These secular trends have been on hold for 18 months now and will see a snap back in 2021.

Beyond China

The Belt and Road Initiative will lead to further Greentech infrastructure projects

China will continue with its multilateral engagement strategy, building off the successes of the Regional Economic Comprehensive Partnership (RCEP) and the China-EU Comprehensive Agreement on Investment from 2020. RCEP’s gradual tariff reductions and rules of origin for manufactured goods will deepen flows of goods between China and the 14 other member economies that in combination represent 30% of global GDP, even if it does little on services.

In 2021, China will also deepen its commitments to standards setting institutions such as the International Standards Organisation (ISO), the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) and more, encouraging its companies and researchers to engage heavily in promoting China developed standards as global standards. In multilateral bodies shaping global climate change policies and global Covid vaccine distribution, China will seek to position itself as a more significant (in terms of offers made) and more reliable partner than the United States.

BRI will continue at scale in 2021. BRI will continue apace, with billions of dollars going into completing the backlog of agreed projects. The year will also see new variants of BRI emerge, for example:

· Green energy BRI – fewer coal and more solar projects, more green finance for projects.

· Smart or Digital BRI, more telecom than road infrastructure, more smart city projects, more smart car projects.

· Healthy BRI covering everything from vaccines to hospitals and digital health solutions

Chinese businesses have low expectations for material change in their ability to do business in and with the United States in 2021. The optimistic hope for stability is simply to be able to better plan, make investment and sourcing decisions with certainty, and to be able to close partnerships with US companies at least in China, if not in the US.

It’s likely 2020 will prove to have been the last wave of Chinese companies listing in the US. This year will see a mix of forced delistings (currently the on again-off again delisting of the three Chinese telecom companies by the NYSE that reinforces the inconsistency of actual US policy towards Chinese business) and companies choosing to re-list in Hong Kong or mainland exchanges, even if they have only been listed in the US for a year or so.

Gradual supply chain reconfigurations will continue. As global trade renormalises China’s share of global manufactured goods, exports will fall back from the all-time high it reached in 2020 on the back of demand for PPE and will return to the gradual trend downwards as manufacturers add incremental new capacity closer to scale markets around the world. As part of this trend, expect to see many more Chinese companies opening factories not just in Vietnam and India but also across Africa, Mexico, Brazil, Turkey and Poland. For example, almost all Chinese smartphone producers now manufacture in India for India.

Companies that manufacture in China for China, whether Chinese or multinational, will largely continue to do so. For most, domestic demand consumes the significant majority of their output. These companies will engage in the growing wave of manufacturing upgrades in China – increasingly the global hub for what the future “smart factory” will look like. Companies that needed to shift production to avoid US tariffs have done so.

China and ESG

Even before President Xi’s commitments for China to become “carbon neutral” by 2060, Chinese businesses had been starting to take environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) concerns more seriously. Consumer, investor and regulator demands were too strong to ignore. For Chinese companies listed in Hong Kong, disclosure requirements by the HKEX become higher each year and force companies to gather and review at board level data that they likely have never looked at before.

Questions from not just ESG funds, but almost all fund managers on ESG, put management on the spot during quarterly reporting calls. Gaining a higher ranking in ESG ratings, schemes from MSCI and Dow Jones are becoming something that company leadership wants to say it is ahead of its peers on. Even on mainland exchanges, one quarter of companies issued ESG reports in 2019, likely over a third did so in 2020, and domestic ESG rating schemes such as the Ping An-CEIS have launched.

Summary

Ahead of the COP meeting in November 2021, it is likely that Chinese regulators will take the opportunity to issue new ESG policies with tougher mandated disclosures. Clearly, there is a wide range of performance on ESG among Chinese companies, with “G” having the furthest to go, but at least on “E”, 2021 will see significant progress.

The 23rd July 2021 is the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party in China, coincidentally also the date of the rescheduled opening ceremony for the Tokyo Olympics. Hundreds of events are planned across China, from movies to parades and political speeches, to celebrate this anniversary. Ensuring all goes smoothly in the run up to the anniversary is a key objective. Domestically that requires stability – social, economic and political – above all else. While pursuing sector specific priorities in 2021, don’t lose sight of this overarching requirement.