Although tax reform is currently not on the Chinese government’s agenda, growing fiscal pain and rising costs for local governments have increased pressure to design a more sustainable tax system, Torsten Weller writes

The publication of China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (FYP) has attracted plenty of international attention, with much of the external commentary on the plan focusing on its emphasis on self-reliance and domestic consumption. One area which has received far less scrutiny is China’s tax regime.

That is an oversight. In fact, a recent decision by China’s State Council has revived the debate over the need for tax reform in China, given the government’s spending plans. On 21 April 2021, Premier Li Keqiang announced that the central government would expand the fund it set up last year to directly help local authorities in supporting employment and economic recovery. The government added that the fund’s scope would be expanded to include the salaries of local civil servants and pension payments.

The fund’s expansion not only increases the central government’s involvement in local government finances, it also raises questions regarding the planned increase of social spending under the new FYP. In particular, the lifting of hukou restrictions for most Chinese municipalities is expected to increase the fiscal burden for local governments. Without a proper tax base, many will struggle to achieve the FYP’s targets.

What is the current tax policy situation in China?

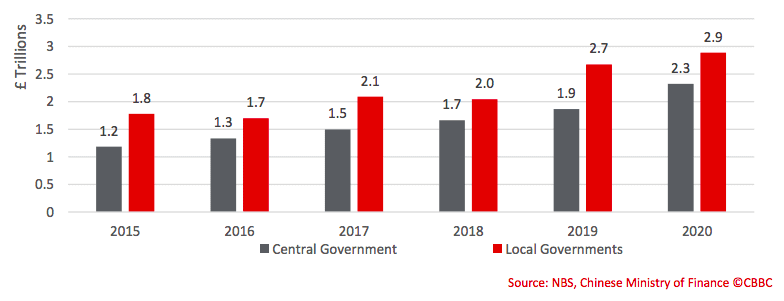

China’s local governments have long struggled with rising debt levels. By the end of 2020, local governments had amassed RMB26 trillion (approx £2.9 trillion) in official debt, up 8% from the year before. Since 2015, this debt has risen by nearly 63%, according to data from China’s Ministry of Finance.

Official debt of central and local Chinese governments, 2015-2020

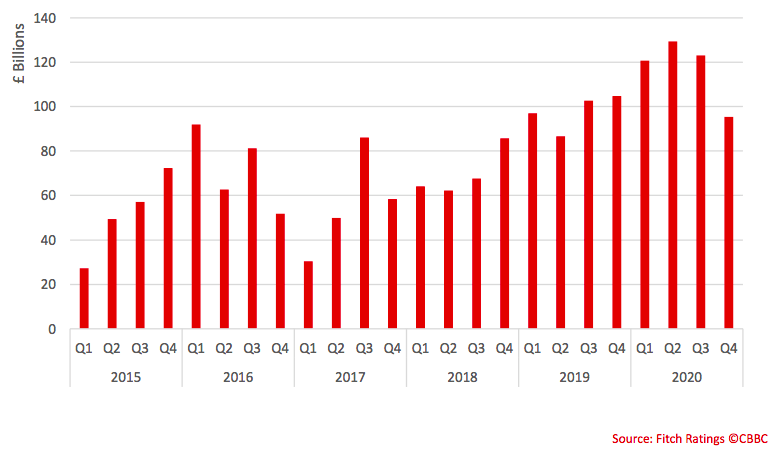

What’s more, most observers agree that these figures are only the tip of the iceberg. Many local governments are known to have considerable off-balance sheet debt, often hidden in so-called local government financing vehicles (LGFV). Between 2015 and 2020, local governments issued over RMB16 trillion (approx £1.8 trillion) in LGFV bonds on China’s onshore market, over 60% more than it accumulated in official debt.

China’s central government has tried to get local debt under control, with varying degrees of success. It has halted expensive infrastructure projects, such as subways and luxury housing projects. It has also signalled that it will not pick up the bill when bonds issued by local governments go into default. Yet reining in spendthrift municipalities has become more difficult just as local government revenue has been dwindling. China’s last major tax reform in 2016 replaced the business tax – which was paid into local coffers – with a value-added tax (VAT) paid directly to the central government. At the same time, the central government’s supply-side reforms further reduced the local tax base by abolishing licensing fees and reducing social welfare contributions.

Even more painfully, Beijing has also started to restrict local governments’ land sales and the conversion of rural land into urban land. Land sales had turned into a major revenue source for local governments, accounting for 55% of revenue last year.

On the same day that the State Council announced the expansion of its subsidy fund for local governments, it also published a new draft regulation making it more difficult for them to seize agricultural land for construction projects. A new law on promoting rural revitalisation would also ban local governments from further reducing agricultural land.

As the fiscal base for municipalities has narrowed, the central government’s reach into local finances has been repeatedly extended. In 2019, the State Council decided that it would share 50% of VAT revenue with local governments. However, most of the transferred money is not shared with local governments directly but is allocated at the provincial level. Unfortunately, owing to the provinces’ own budgetary constraints, most of these shared revenues fail to reach the local level, according to a 2020 working paper from the Asian Development Bank.

LGFV onshore bond issuance, 2015-2020

The Chinese government, therefore, decided to establish a fund to help local governments directly. This became particularly urgent during last year’s lockdown when the majority of municipalities had to halt most of their economic activity. Initially, the government earmarked RMB1.7 trillion (approx £190 billion) for the fund, which was aimed at supporting local employment and small businesses hit by the pandemic. Since last year, however, the fund’s value has increased to RMB 2.7 trillion (£300 billion) – an increase of nearly 60%. Its purported use has also been broadened to include social welfare payments and education – two areas which previously were borne exclusively by local governments.

What are the chances of tax reform in China?

Centralisation has been a general feature of administrative reforms under Xi Jinping. But the recent measures represent the largest appropriation by central authorities of local prerogatives so far. Even though the demographic disparities – for example in local pension funds – warrant stronger coordination at the national level, the inability of many local authorities to even meet basic fiscal needs has increased the need for a more sustainable tax system.

Yet the 14th FYP contains little to suggest that tax reform is on the agenda. The term ‘demand-side reform,’ which briefly appeared in the communique of last year’s Central Economic Work Conference and could have indicated significant changes to China’s welfare regime, was quietly dropped from the FYP. This year’s legislative plan does not mention any tax-related items either.

Instead, Chinese policymakers continue to call for further tax cuts and fee reductions. At a press conference in early April, Assistant Secretary of the Ministry of Finance, Ou Wenhan, rejected calls for broader tax reform and reiterated the government’s avowed goal to reduce costs for manufacturers and small businesses.

Nonetheless, the government wants to support charitable activities – so-called ‘tertiary wealth distribution’ – and crack down on tax fraud and tax evasion by China’s wealthiest. A planned property tax, which has been debated for years, would probably also target the well-off middle class in China’s rich coastal regions. As China research director for Gavekal Dragonomics Andrew Batson wrote in a recent blog post, the government’s current agenda seems to be one of tougher legal and political scrutiny of high-income and high-net-worth individuals rather than of generalised welfare reform.

Such an approach, however, does little to address China’s structural and regional inequalities. Especially China’s ambitious hukou reform – bringing hundreds of millions of new entrants into the country’s urban welfare network and education system – will make such an approach difficult to sustain. Worse, it could boost the coffers of already rich cities like Beijing or Shenzhen while leaving their poorer peers in a perpetual state of fiscal penury.

The CBBC view

Although tax reform is currently not on the Chinese government’s agenda, growing fiscal pain and rising costs for local governments will increase the pressure on Beijing to design a more sustainable tax system.

In the short term, the Chinese authorities are likely to focus on improving the efficiency of tax collection from high-net worth individuals. High-profile cases like that of actress Fan Bingbing, who in 2018 was fined £98.9 million for tax evasion, might become more commonplace. We should also expect more pressure on China’s large companies – both private and state-owned – to spend more on social and educational projects.

But given the enormity of Chinese local debt, such measures amount to little more than a drop in the ocean. China’s current central state apparatus is also unable to effectively supervise the correct use of its direct funds. A full 90% of last year’s direct funds were distributed within 20 days, according to China’s Finance Minister Liu Kun. This suggests that there was only minimal verification of whether the money really went to the right places.

We therefore expect that more comprehensive tax reform is needed to meet the growing fiscal commitments of local governments.