Following the Chinese government’s announcements to reduce the financial burden on the private sector, 27 local governments have reduced the mandatory contribution to the pension fund from 20 percent to 16 percent for local companies.

Although this is good news for businesses, China is nonetheless facing increasing pressure to reform its pension system. With an aging population, local governments are confronted with rising costs for its senior citizens at the same time as the working-age population is shrinking.

This has put considerable stress on provincial pension funds, with some provinces, such as Heilongjiang, already spending more than they receive from contributions. According to a study conducted by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, on the national level, pension funds could be fully depleted by 2035.

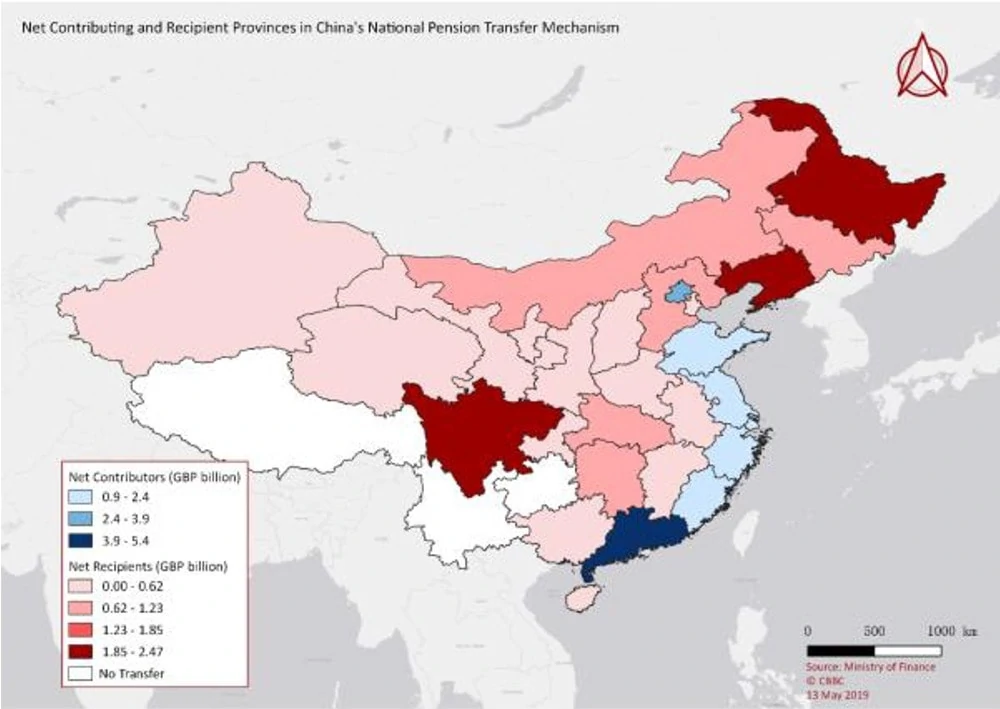

In order to help provinces with a disproportionate number of older people, China established a national transfer mechanism in July 2018. The mechanism would take surplus income from richer provinces and redirect it towards provinces with deficits. In early April 2019, China’s Ministry of Finance published4 its first budget for the transfer mechanism. The figures reveal stark inequalities between provinces.

However, the numbers also offer a useful insight into the shifting demographic situation in China and could be a precursor for future reform initiatives.

China’s march towards a universal pension system

China’s pension system dates back to 1955. However, it only covered civil servants and urban workers in the state sector. Under this system, each company managed its own pension fund and contributions and payments were handled on a pay-as-you-go (PAYGO)-basis. As the economy began to liberalise in the 1980s, this system become unsustainable and in 1991 the government created a regional fund which would cover all enterprises.

The new system rested on two pillars. The first one is an earnings-based pension following the PAYGOprinciple with defined benefits for retirees. The second pillar consists of forced savings into an individual pension account. Both relied on mandatary contributions from both employees (8 percent) and employers (20 percent). Although this reform vastly expanded the safety-net, it still covered only around 30 percent of urban residents5 in 2005. Rural workers remained excluded.

After a failed experiment with voluntary contributions, it was not until 2009 that the Chinese government managed to set up a universal non-contributory pension system for rural residents. Two years later, this basic insurance scheme was extended to non-working urban residents.

In 2014, both systems were finally unified into one single basic pension scheme, and in 2015, the State Council abolished the separate system for SOE employees and civil servants and merged their accounts with the general system.

Geographical disparities

Despite the continued expansion of China’s minimum pension insurance, considerable inequalities between regions remain, especially with regard to pension funds that rely on contributions by employees and companies (1st pillar).

The published budget for the transfer mechanism testifies to the considerable problems faced by many provincial pension funds. In total, the mechanism will reallocate £13,96 billion. However, only seven provinces are net-contributors, with almost 40 percent borne by Guangdong alone. The other net payers are Beijing, Shanghai, and the coastal provinces of Shandong, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Fujian. Three provinces, Guizhou, Yunnan, and Tibet are spending as much as they earn, whereas the remaining 21 provinces are all net-recipients. The biggest beneficiaries are Liaoning, Heilongjiang, Sichuan, Jilin, and Hubei, which, taken together, receive 63 percent of the funds.

Continuing problems and outlook

While the transfer mechanism might help to stabilize some of the struggling pension funds, it raises serious questions about the sustainability of the scheme. Given China’s overall demographic trends, it is likely that the amount required will further increase at the same time as the number of net-contributors shrinks.

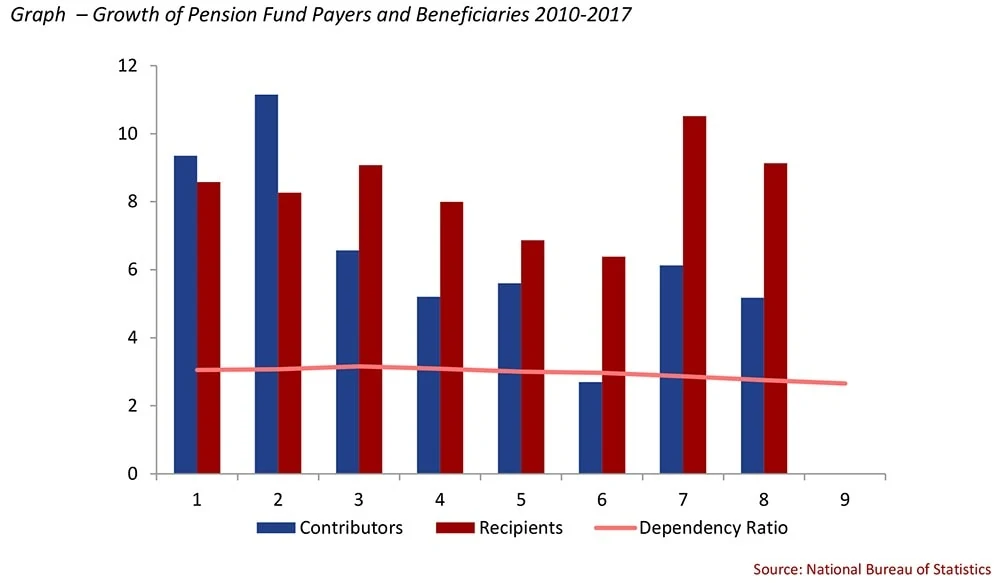

What’s more, since 2012 the number of eligible recipients has grown faster than that of new contributors. Although the share of the participating working population has increased over the years from 23 percent in 2009 to over 36 percent in 2017, the number of retirees has grown even faster. In 2010 the number of contributors increased by 9.4 percent against a rise of 8.6 percent for recipients, whereas since 2012 the latter was consistently higher than the former. In 2015, the growth of the number of eligible pensioners was even more than double the increase in contributions, pushing down the dependency ratio from 3.16 in 2011 to 2.65 in 2017.

The impact of China pension problem on reforms

The woes of China’s pension funds have considerable ramifications on China’s reform efforts. First, the need for additional capital has likely stalled the long-awaited reform of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), as their assets have been used to plug the funds’ holes. This has made any privatization politically costly and has increased the government’s efforts to buttress the ailing state-sector despite low productivity and misallocation.

Second, the low level of state pensions and the lack of private alternatives have prompted many Chinese to invest in real estate and the stock market, thus fueling bubbles and encouraging rent-seeking. This has led to repeated government intervention in order to stabilise prices far beyond market rates.

Building a third pillar

In order to alleviate these problems, the Chinese government has made several efforts to add another pillar to the pension system. It has thus encouraged Chinese employees and pensioners to invest in private pension schemes, which could help raise the general pension level and ease pressure on public funds. Unfortunately, poor regulatory oversight, lack of professional risk management and low financial literacy rates have created a breeding ground for fraud and greed. In April, the Chinese journal Caixin reported of the real estate company Zhongan Minsheng Pension Service Co., Ltd. having convinced retirees to invest in apartments in Beijing’s high-end Haidian district. The investors would then receive an annual return of 4 percent- 6 percent, paid as monthly supplement to the state pension. However, in February 2019, the company stopped making payments and shortly after ceased operations completely, leaving one investor with a private debt of £340,000.

To avoid such scandals in the future, China’s government is pushing for further reforms. On 29 March 2019, the State Council published a document which called for further reforms to broaden investment channels for retirees. These include the promotion of financial pension services, an expansion of corporate bond issuance in the old-age care sector, and, most importantly, better access for foreign financial pension fund providers.

Although it might not solve the underlying structural problems, an effective opening up to international investors with a global portfolio could at least provide Chinese pensioners with a viable and comparatively safe alternative, especially given the vulnerability and fragility of China’s own financial and real estate markets.

Lessons for UK companies

Although China’s pension crisis might raise costs for businesses in China, it also offers new opportunities for UK financial institutions and Fintech companies. According to a 2017 research report9 by KPMG, China’s private pension insurance volume could reach GBP 1.3 trillion by 2025.

As pressures grows on the government to provide reliable and well-managed investment opportunities for an aging workforce and growing number of middle-class retirees, an accelerated liberalization of China’s financial markets, especially in the insurance and retirement fund sectors, looks more and more likely.

However, an effective operation in China for UK fund managers and investment companies will also require additional reforms in China’s domestic capital markets and reduced capital controls, without which foreign institutions might face the same risks as domestic investors.