By Helen Roxburg

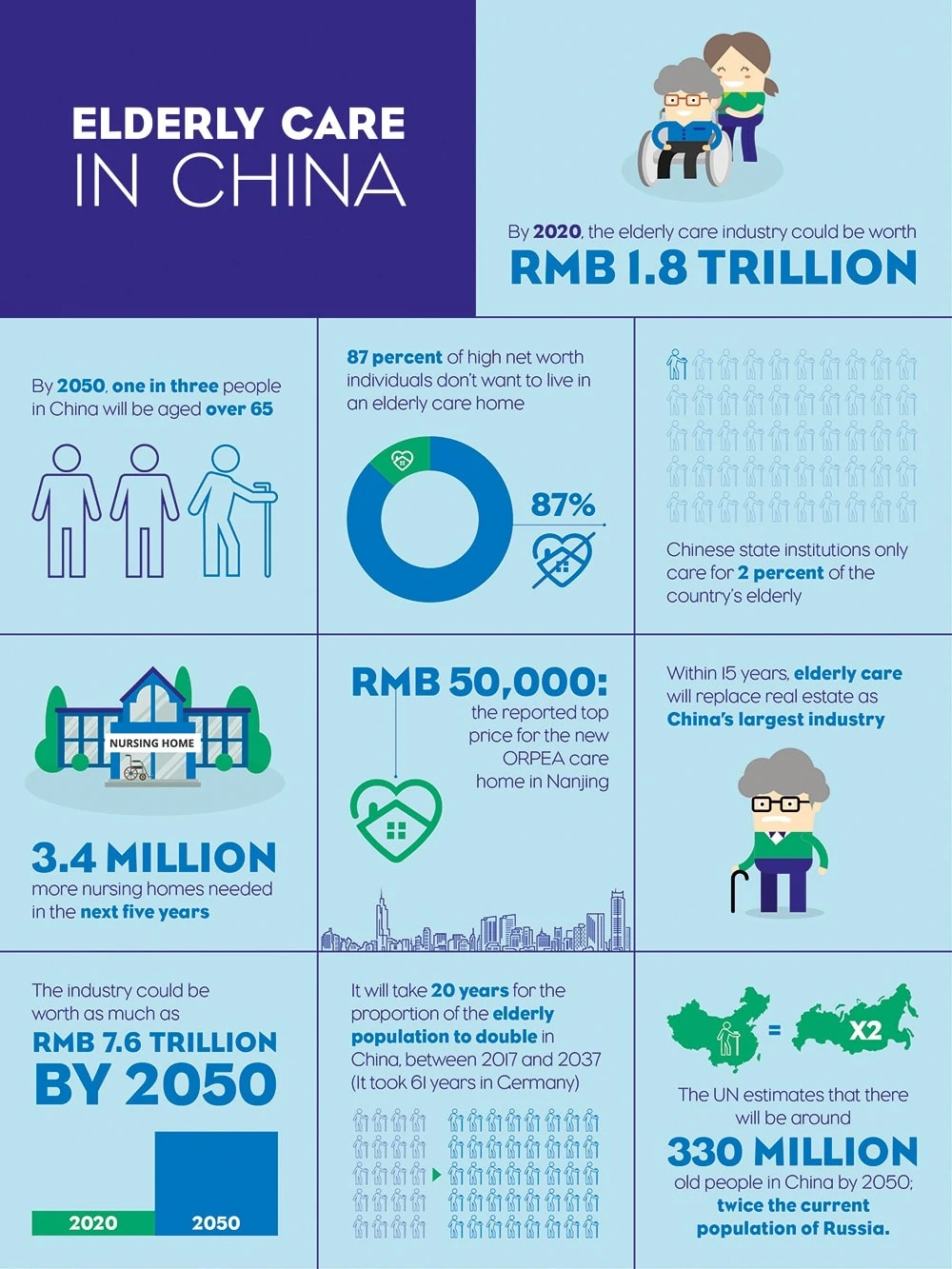

With the fastest-ageing population in human history, China is heading into a demographic crisis. The country’s over-60 population reached 222 million in 2015 – 16.1 percent of the population – a rate predicted to grow by three percent annually. By 2050, one in three people in China will be aged over 65.

This change has huge social, economic and political implications. Although younger generations have traditionally looked after ageing relatives, mass rural migration means many children now live and work far from their hometowns. The one-child policy has further compounded the problem, leaving working-age children to care for two parents and four grandparents. China’s traditional multi-generational households are no longer practical for many families.

Yet the country is vastly undersupplied with elderly care accommodation. Currently, state institutions only care for two percent of the elderly population and 18 percent of its disabled elderly population, and there are only around 42,000 private facilities. Official estimates say an additional 3.4 million nursing homes will be needed within the next five years alone.

Various approaches have been considered to alleviate the pressure. One nursing home in Suzhou gave vouchers of RMB 200 to people who visit their elderly parents regularly. This incentive follows a law introduced in 2013 which said adult children must visit their parents frequently or face punishment.

But what remains conspicuously absent is a well-developed and regulated care home sector.

“There’s currently a big push towards not only creating a sector that doesn’t exist yet, but also towards creating standards and qualifications for people working in that industry,” says Robin Weir, senior associate at Dorsey & Whitney in Shanghai. “If you’re going to suddenly have an elderly care sector, where are you going to find all the people to do the work? There’s a great need to create standards for elderly care and the people who work in it.”

By 2050, one in three people in China will be aged over 65

This demand is creating opportunities for international companies to bring their expertise to China. In 2014, the national government confirmed that foreign investors could establish for-profit elderly care institutions, and last year the Beijing government said it would further open its elderly care market up to private institutions in the city.

A series of recent UK trade delegations have brought interested parties to China to explore opportunities. In January 2016, 21 British companies met a stream of customers at Zhejiang International Healthcare Expo in Hangzhou, and then at Care Expo in Shanghai.

Shaw Healthcare is planning to be one of the first UK operators in the Chinese market. The company has been operating in China for almost two years, offering both consulting and training, and are now preparing to open a 226-bed care home in collaboration with Chinese giant Fosun Group.

“We are focusing our first centre on short term rehabilitation; China faces a challenge with hospitals overflowing with patients, especially elderly people,” says David Gray, China Director for Shaw Healthcare Group. “They are medically stable and able to leave the hospital, but not medically stable enough to go home, and at the moment there’s just nowhere in the middle for them to go to. What we are trying to do is develop something new for China, a step down service which gives intensive rehabilitation care for a period of about six to eight weeks.

“Because the centre has a medical license issued by the local medical health bureau, a patient’s care is covered by health insurance, so about 50 percent of the fees for the individual can be claimed back through the public healthcare system.”

The industry is estimated to be worth 1.8 trillion RMB by 2020

Several international operators have already opened in this field. French nursing home operator ORPEA opened its first nursing home in the eastern city of Nanjing in January 2016, a 139-bed premium facility that reportedly charges between RMB 20,000 and RMB 50,000 per month. Other organisations are also working with Chinese real estate developers.

“There are property developers and other big state-owned groups which are looking at this sector and have the financial resources, but not the experience,” says Weir. “That’s when foreign providers with expertise are very useful. Often these groups have buildings, which need to be converted for elderly care, and there is work to be done with staffing, putting in good management systems – the whole world of how you run a care home.”

UK healthcare company Annie Barr Associates is currently providing training and consultancy in China, as well as developing concepts around remote healthcare monitoring, using digital technology and IT skills to help enable better elderly care.

In a similar field, a new Sino-UK Health Big Data Park is being developed in Guiyang, south-west China, where 30 organisations from mostly the UK and China are bringing together new digital technologies to remotely diagnose and monitor people in their own homes. Nine Health Global is one of the UK companies involved in the project, focusing on care that can be delivered earlier and more efficiently to a greater number of the population at a much lower cost. They are also planning to bring new technology to a purpose-built older care village of 170,000 residents.

“You don’t want people to go to hospital or a nursing home if they don’t need to, it’s much better to care for them at home,” says Annie Barr, of Annie Barr Associates. “We are looking at new models, and new care approaches for China, and we are finding the appetite is definitely there.”

However, complex and obscure regulations are often a problem, as are extremely localised markets, making it difficult to roll out a business model across the country. Many international operators have been looking at high-end developments in order to recoup costs, but the greatest need for senior care in China is in the mass market.

Research from analyst Rubicon Strategy Groups suggests the elderly in China are not yet prepared for care homes. In its research, the group found nearly 87 percent of high net worth individuals want to stay put in their homes, although the majority of their children said they would prefer a senior living home.

A cultural gap therefore needs to be bridged. Elderly care homes in China have typically been poor quality, built and run by those with little experience of the sector, and therefore, many of the older generation in China have been reluctant to consider them. In addition, it has been seen as a loss of face if younger generations don’t care for their elderly relatives.

However, the necessity of the situation looks set to help change attitudes, with enormous numbers of elderly people needing additional support, set only to increase through the next decade. Research from law firm Dezan Shira & Associates said elderly care will surpass real estate as China’s largest industry within 15 years, and is estimated to be worth RMB 1.8 trillion by 2020.

For UK companies, especially those with skills in new technology, the opportunities in the sector are vast. “There are tremendous opportunities in older care in China, particularly in health improvement and prevention, as well as remote telehealth and telecare,” says Eileen Taylor-Whilde CEO at Nine Health UK. “The population is ageing and there is a significant requirement for purpose-built older care facilities and to extend the reach of care to those who are unable to access it and those living in rural areas.

“The challenges for us are all about forgetting the Western healthcare ways of working, and listening to the wishes of those developing and delivering care in China.”