China’s Export Control Law took effect on 1 December 2020, making it the first comprehensive and unified export control law in China. Here, Li Chengrong, Gao Xi and Lv Sixuan of Zhonglun Law Offices explain it in more detail

The Export Control Law (ECL) not only draws attention to the widely-defined control list of exported items and the temporary control regime – which used to be stipulated by scattered regulations and policies – but also brings in remarkable regulative measures such as a licensing system and reporting obligations to enhance the state’s systematic control on export activities.

Other than shedding some light on a few key provisions in ECL, this article aims to go a step further by using cases and examples to illustrate who should be most concerned about these new regimes, what new rules to be wary of, and more importantly, how companies and the responsible persons in those companies should prepare for the impacts of this law from corporate governance and risk management perspectives.

Who should be concerned about ECL?

Businesses may come across controlled items or unwittingly behave in a way now regulated by ECL, and thus are required to comply with the relevant rules. So here we will summarise three types of market participants that are most likely to be impacted by ECL: (i) exporter (including re-exporter, deemed exporter and other exporters); (ii) importer and end-user; and (iii) third-party service provider. The following paragraphs explain why and when a business needs to be concerned about ECL rules.

Exporters:

Any person (including individual, company and other organisation, etc.) who intends to export or engages in export transactions that are associated with controlled items on the control list or fall under temporary control (or are considered to be relevant to public security and public interests of China) may be regulated by ECL, and shall obtain an export licence from the relevant competent State Export Control Authorities (SECA) in China for exporting such controlled items.

The scope of ‘export’ as interpreted under ECL encompasses more than what you might normally think of as restrictions imposed on a Chinese vendor who sells a domestic product to an overseas purchaser. ECL puts in place certain control and monitoring measures to oversee any person who carries out re-exporting or exporting activities.

Re-exporters:

There is no clear and precise description in respect of ‘re-exporter’ or person who carries out ‘re-export’ transactions under ECL. It is widely believed that re-export takes place when an imported product is then exported by the original importer to a subsequent importer. As such, any person who re-exports controlled items is equally required to obtain a licence for exporting such controlled items.

However, ECL remains silent on the ‘de minimis rule’, which was proposed in previous review drafts – namely, whether an export of uncontrolled products with a certain proportion of controlled items will be regarded as re-export. In the previous review draft of ECL, the definitions of re-export and re-exporters set out a detailed percentage threshold for controlled items, but such threshold was eventually removed. By disapplying the ‘de minimis rule’ in ECL, it may imply that the re-export of foreign-made products containing China-made controlled contents is not subject to ECL regime. However, it could also mean that there is room left for future administrative regulations to set a threshold. Future administrative regulations may further clarify the scope of re-export and, in particular, the ‘de minimis standard’. It is therefore important to be wary of the uncertainties and risks based on the above mentioned rule.

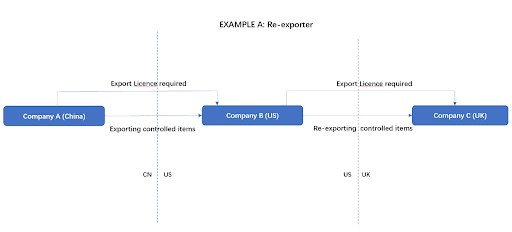

Example A: Re-exporter

Chinese company A exports controlled items (e.g. dual-use products) to American company B, after which British company C imports the controlled items from the United States. In this case, (i) Chinese company A (acting as the original exporter of the controlled items), (ii) American company B (acting as the re-exporter of the controlled items) will need to comply with ECL rules in particular in obtaining the licence for exporting (and re-exporting) controlled items.

Deemed exporters

ECL widely catches and regulates any person whose behaviour may be categorised as a ‘deemed export’, which refers to the provision of controlled items by a citizen, legal person or unincorporated organisation of the PRC to a foreign organisation or individual, catching any non-cross-border exporting activity, no matter what form it takes. Exporting controlled items to any foreign person may be deemed as an export under ECL, regardless of whether such foreign importers are located or based within or outside China. In other words, an ECL-regulated export does not necessarily have to be a typical cross-border export transaction.

Exporting controlled items to any foreign person may be deemed as an export under ECL, regardless of whether such foreign importers are located or based within or outside China. In other words, an ECL-regulated export does not necessarily have to be a typical cross-border export transaction.

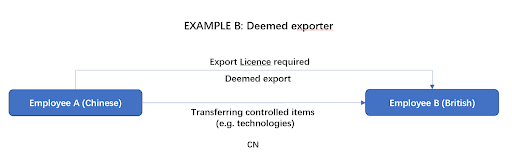

Example B: Deemed exporter

Employee A (Chinese nationality) and employee B (British nationality) both work in companies located in China. Employee A may be deemed as an exporter under ECL if he or she transfers a controlled item (e.g. restricted technology) to employee B in the course of business (e.g. via electronic form), regardless of the actual place where the importer (employee B) is located and the form of such transfer. In this case, employee A will be required to obtain a licence for exporting such technology to employee B.

Other exporters

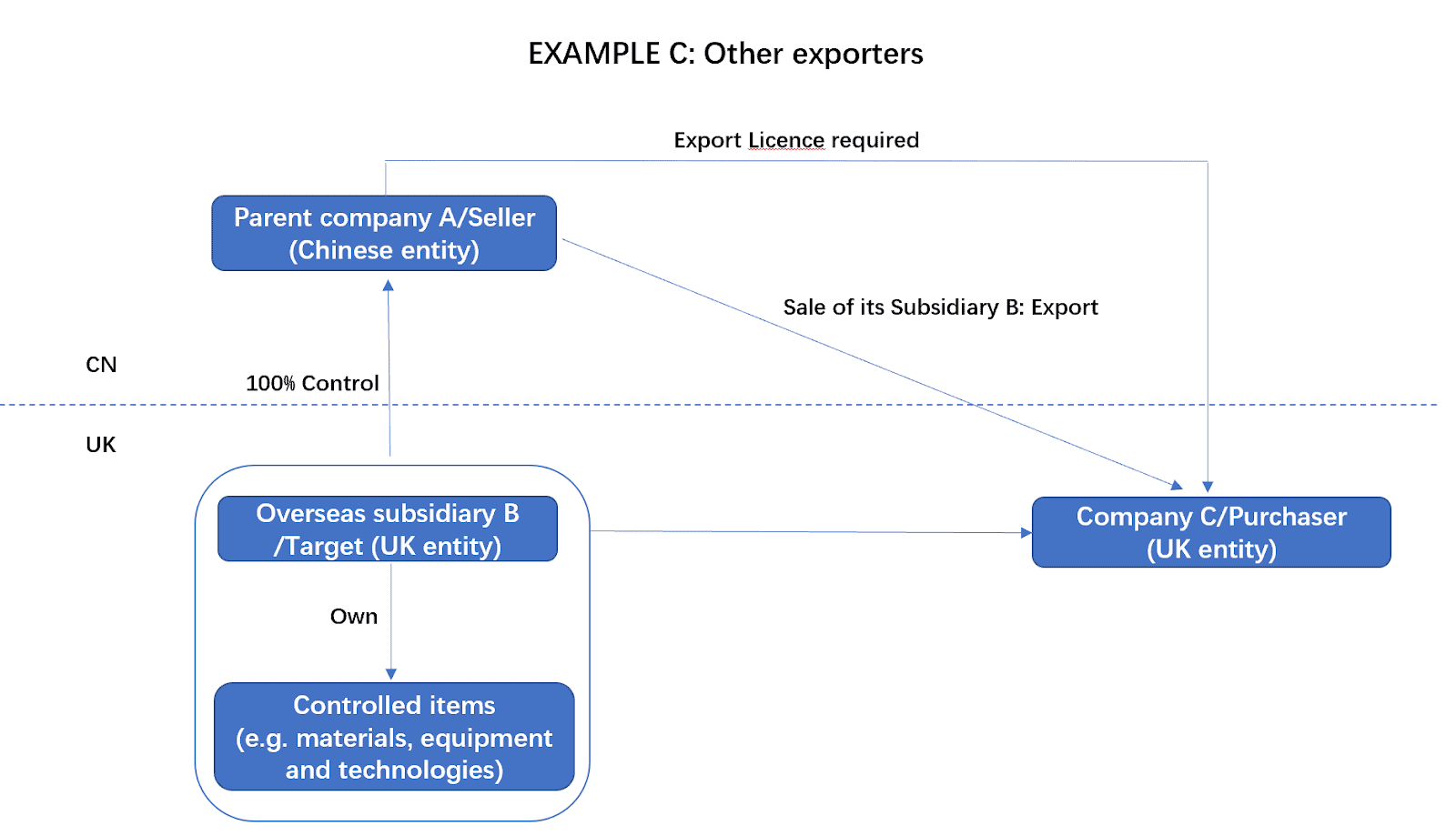

The broad definition of ‘export’ may also catch mergers and acquisitions. If the sale of a company involves controlled items or is subject to SECA’s temporary control, the transaction is likely to be governed by ECL. Since ECL has just come into effect, we will use the recent case of TikTok to illustrate how the term ‘exporter’ might be interpreted under ECL in practice.

Example C: Other exporters

In 2020, TikTok’s China-based parent company, ByteDance, was forced to sell its US operations to a US-based company under pressure from the US government. At that point, an adjusted catalogue of prohibited and restricted technologies for export was issued in China, including text analysis and content suggestions-related AI technologies – which are the core algorithm of TikTok’s US business. If ByteDance insists on selling its US operations with its core algorithm, it should make an application to SECA for export licence before such sale can proceed.

With the promulgation of ECL, the sale of a company or business associated with controlled items to a foreign purchaser, regardless of whether the sale takes place domestically or in a foreign country, could be caught by ‘export’ under ECL, and therefore triggers the seller/exporter’s obligation to obtain an export licence before proceeding with the sale.

Taking the example of the TikTok case (see chart below), we can deduce that if Chinese parent company A wishes to sell its overseas UK subsidiary B to a UK company C and the subsidiary B owns materials, equipment and technologies on the control list or subject to SECA’s temporary control, the sale will constitute an ‘export’. As such, it will be subject to the licensing regime under ECL. The parent company A will be required to obtain a licence for selling its subsidiary B to the UK company C.

Importer and end-user

As one of the conditions to trade, ECL requires exporters to provide certificates or evidence issued or provided by importers and end-users’ relevant competent authorities to declare the purpose and use of the controlled items. Moreover, ECL extends its power to regulate and supervise importers and end-users who are important counterparties in export transactions. One of the main obligations of importers and end-users is to use the controlled items only for the declared purpose and not to transfer controlled items to any third party without notifying or obtaining prior approval from SECA. Failing the above, the company may face a sanction by SECA.

It is equally important for exporters to check on day one and ensure that the importers and end-users with whom they propose to conduct business are clear of the Blacklist stigma

Blacklist/Controlled person list

Pursuant to Article 18 of ECL, an importer or end-user will be put on the blacklist or controlled person list if it:

- breaches regulatory requirements regarding end-users or end-uses; or

- endangers national security and national interests; or

- uses any controlled item for terrorism purpose.

(hereinafter referred to as the ‘Blacklist’)

For any importer or end-user that is put on the Blacklist, SECA may take necessary measures such as prohibiting or restricting its importation of controlled items. Any person on the Blacklist can apply to SECA to have it removed from the Blacklist if it can demonstrate that it is no longer in breach of the relevant rules and appropriate remedies have been taken effectively.

It is equally important for exporters to check on day one and ensure that the importers and end-users with whom they propose to conduct business are clear of the Blacklist stigma. SECA may prevent any exporter from exporting any controlled items to any person on the Blacklist in the first place. However, in exceptional cases, an exporter may be allowed to apply for permission from SECA for proceeding with the export to any person on the Blacklist, provided certain conditions and requirements are satisfied.

The consequences of an importer or end-user being listed on the Blacklist could be serious, considering the strict ban applied on import transactions. Whilst we are as yet unable to evaluate the complexity of obtaining permission from SECA without examples of practical application of ECL, the US Export Administration Regulations (‘EAR’) may enable us to infer how ECL Blacklist is to function. In this respect, the case of ZTE may help to demonstrate how wide the impact of ECL might be on importers.

The ZTE case

On 1 July 2010, US President Barack Obama authorised new sanctions against Iran. Embargoes were placed on dual-use items produced by US companies. In 2012, ZTE provided Iran’s largest telecommunications operator (TIC) with equipment which had US software installed. In 2016, the US Department of Commerce published an investigation report and stated that ZTE illegally exported US-origin items to Iran. ZTE was found to be in violation of EAR. As a result, ZTE Corporation was put on the ‘Entity List’, and export restrictions were enforced against ZTE.

In March 2017, in hopes of being removed from the ‘Entity List’, ZTE agreed to pay approximately US$890 million in fines to reach a settlement with the US Department of Commerce.

ZTE, as a Chinese telecommunication company, has no branch or office in the US. However, as demonstrated by the case, it does not mean that American laws will have no influence over it. Importing controlled items and then exporting them to a country or an entity being sanctioned would be a clear breach under American laws. It is envisaged that ECL will have control over importers and end-users in ways similar to EAR. As such, overseas importers and end-users should be cautious about whether or not the transaction involves any controlled item imported from China or the contracting party is sanctioned by ECL.

Third-party service provider

Similar to the EAR system, ECL prohibits any person from providing agency, freight, delivery, customs clearance, third-party e-commerce trading platforms, financial services or other services to any exporter who engages in transactions that violate ECL. It is important to note that Article 20 of ECL does not provide an exhaustive list. That is to say, even if the service carried out by a third-party service provider does not fall within the listed categories as set out in Article 20, the person should still be mindful that any means of assistance to the exporter acting against ECL may in itself constitute a violation of ECL.

What items will be restricted? – The control list and temporary control

Control list/Controlled items list

ECL imposes export control measures over ‘controlled items.’ The definition of ‘controlled items’ includes dual-use items, military items, nuclear items, as well as other products, technologies, services and items that are related to the maintenance of national security and national interests, performance of anti-proliferation and other international obligations. The unified export control system is to be administered through making lists, directories, or catalogues of controlled items and implementing export licensing system. The lists, directories, or catalogues may be adjusted from time to time pursuant to ECL and other relevant administrative regulations. In that case, SECA will work with the related departments to establish and adjust the control lists, and promptly publish such lists in accordance with export control policies.

Temporary control

For items not listed on the control list, there remains the possibility for SECA to amend the list and supplement those items to the extent it considers necessary in maintaining national security in China. This is referred to as the ‘temporary control regime.’

SECA is authorised to impose temporary control over items for a period of no more than two years if those items are not on the control list. Before the expiration of any temporary control period, an evaluation will be carried out and SECA will decide whether to cease, extend or change the temporary control based on the result of the evaluation. Meanwhile, ECL provides that if any foreign country or region ‘abuses’ its export control measures to endanger China’s national security and interests, the Chinese government can take reciprocal countermeasures against such foreign country or region.

If any foreign country or region ‘abuses’ its export control measures to endanger China’s national security and interests, the Chinese government can take reciprocal countermeasures against such foreign country or region

The temporary control regime may bring uncertainties to overseas companies that have or will develop trade relations with entities or people in China regardless of any relevant jurisdiction or nationality of that entity or person. At the same time, it could be challenging for overseas companies to predict the impact of ECL on any existing or future trade relations considering the difficulties in anticipating the risks of being caught by the temporary control regime.

So, how do you comply?

Despite the fact that ECL has already been in effect since 1 December 2020, people are expecting more bylaws to be put into place and to guide market participants on how to adapt to China’s export control regime. Meanwhile, here are some specific measures that SECA encourages companies to adopt in order to comply with ECL.

Licensing regime

It is mandatory for exporters to obtain an export licence from SECA if they intend to export any items that are listed on the control list or may be caught by the temporary control regime.

When assessing exporters’ applications for the export licence, SECA will take into account the following factors:

- national security and interests;

- international obligations and commitments;

- the type of export;

- the degree of sensitivity of the controlled item concerned;

- the export destination country or region;

- the end-user and the end use;

- the exporter’s credit records; and

- other factors as prescribed by law or regulations.

Reporting changes of end-users or end-use

As one of the requirements for granting export licences, SECA will have to be satisfied that the documents provided by the exporters have established the proposed usage of the controlled items and the target end-users. Proof of identity and detailed information are also required from the target end-users. Should there be any change of the originally-registered usage of controlled items or the target end-users, both the exporter and the importer have an obligation to report to SECA. As a key regulatory measure, SECA will constantly monitor the compliance of the end-users and end-uses through a risk management system, details of which are to be further clarified by SECA.

Internal compliance system

If an exporter establishes an internal compliance system for its exporting behaviours and such a system proves to function effectively, SECA may consider granting general licence or applying other facilitation measures to such an entity for carrying out export business. Only exporters can benefit from such measures. In this respect, for exporters that wish to take advantage, we would suggest they plan and establish such internal compliance systems as soon as possible to allow more time for adjustments.

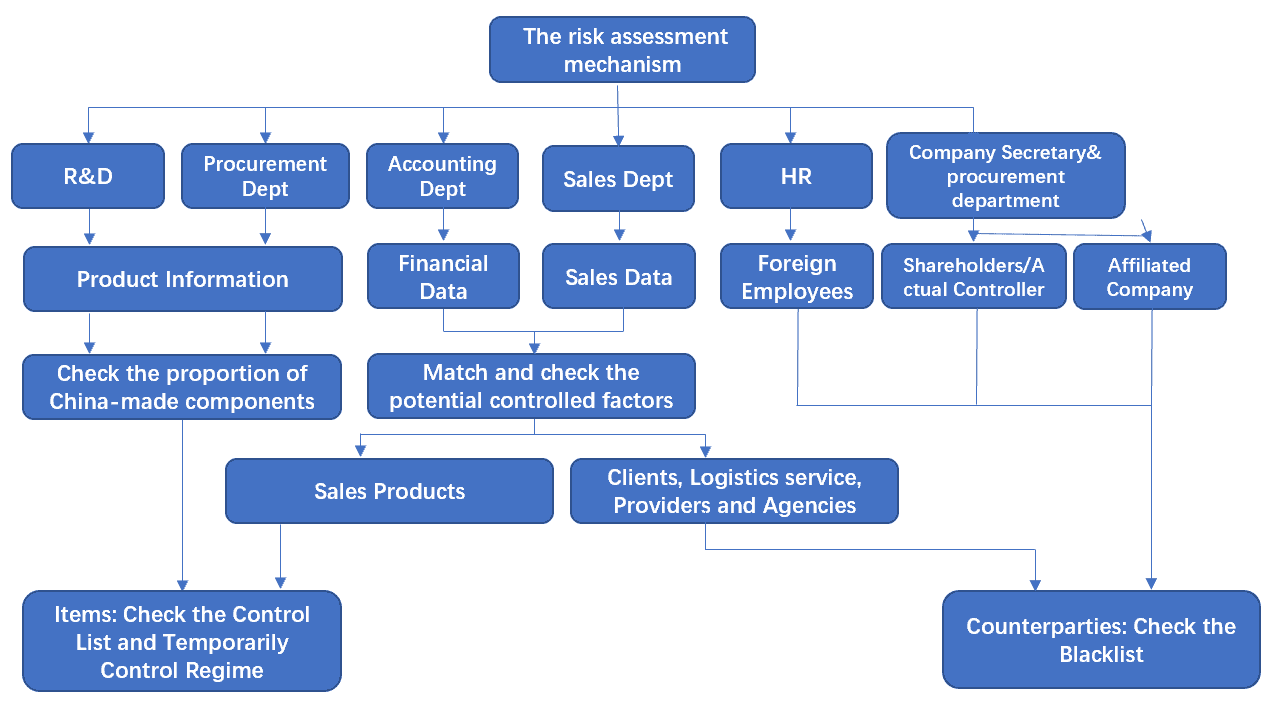

Establishing and improving the risk assessment mechanism for export control

The risk assessment mechanism is different from the aforementioned internal compliance system. We recommend that any relevant party, including exporters and importers, should develop and maintain a risk assessment mechanism as an additional assurance for any export and import activities. For example, within an importer’s company, before its directors and/or shareholders approve any import transaction, it is in line with the company’s interests to fully investigate the exporters and end-users and to evaluate the underlying risks with regard to all key aspects of such import transactions under ECL.

In general, the objective of the risk assessment mechanism is to uncover whether or not the target company, i.e, the counterparty in any export and import transaction, has engaged in any export or import violations or may in any way be restricted under ECL. The information to investigate into may include at least two major aspects: information about the exported or imported items, and information about the counterparties.

Firstly, the company should draw up a list of documents that it may require from the target company on a case-by-case basis. For example, depending on the scale of transaction and the particular counterparty, the company may collate and review the relevant information of product and core technology used in the exported items, the financial data, sales data, and the shareholding structure of the target company. In situations where the target company is reluctant to provide all required information, the company should consider trimming their list of required information down to a reasonable extent which is acceptable to the company from risk assessment perspective.

Secondly, the company may also look into other indirect information during the investigation process in order to figure out whether or not the type of transaction is or is likely to be subject to the scrutiny under ECL regime (for example being re-export or deemed export) and to what extent it may be restricted. Ways to acquire such information can include inquiring into relevant foreign employees in the target company and examining the proportion of China-made components of the exported items.

Following proper risk assessment procedures, the company may either find that the exported or imported items are not involved in the control list and neither do they fall into temporary control, and also that the target company is not on the Blacklist, or may conclude that the target company or the traded items are restricted by ECL and therefore requires export licence or permission from SECA.

If the exporter insists on trading with an importer or end-user on the Blacklist for some reason, permission must be obtained from SECA before carrying out the transaction or entering into any transactional documents

What should you do if the traded item is found on the control list or is subject to temporary control?

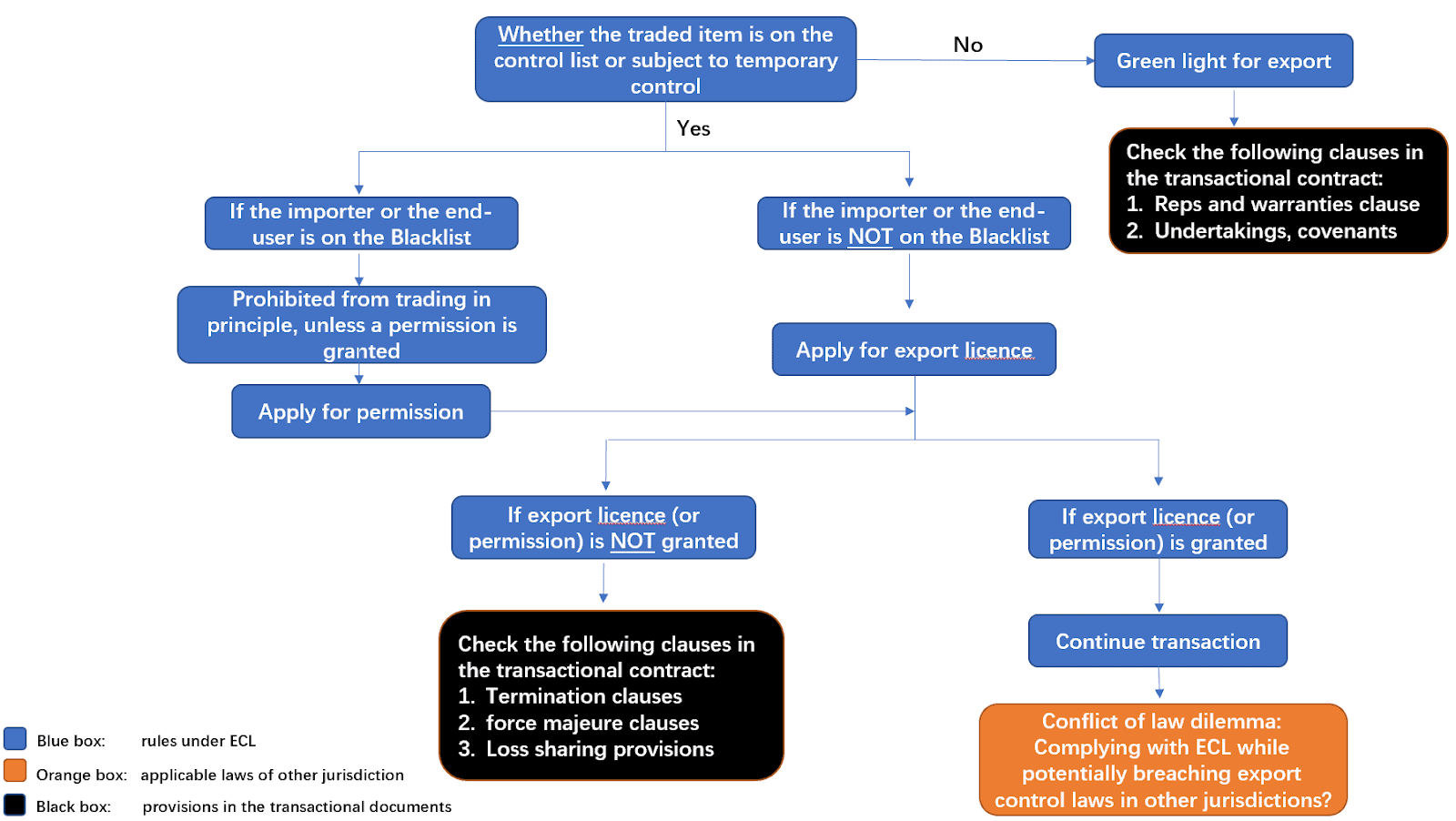

Where the import or export of items is explicitly prohibited by ECL, the companies should avoid entering into a contract for such a transaction. Nevertheless, for those not strictly prohibited, the following chart provides general guidance on how to conduct the transaction cautiously.

As shown in the chart, the exporter shall firstly check if the importer or end-user is on the Blacklist.

If the answer is yes, then the exporters should be alarmed and try to avoid trading with those entities. If, however, the exporter insists on trading with an importer or end-user on the Blacklist for some reason, permission must be obtained from SECA before carrying out the transaction or entering into any transactional documents.

If the answer is no, the exporter shall request for a licence from SECA, which we understand could be much simpler than applying to obtain the permission where the importer or end-user is on the Blacklist. In this respect, we would suggest parties document and make a record of any effort which the exporter makes to obtain such licence, including, without limitation, to any statements or certifications the importers and end-users are requested to provide and have actually provided throughout the trading process.

Nevertheless, if the application of the export licence is rejected by SECA, the parties to any already-executed transactional documents should then check the termination clauses, force majeure clauses and loss sharing provisions to deal with the risk allocation between parties to ensure that the transaction and the relevant documents comply with ECL and any other applicable laws of China and the relevant jurisdictions concerned.

In other words, for any to-be-executed transactional documents, parties should be mindful of carefully drafting and negotiating the relevant provisions to eradicate, or at least mitigate, the risks. We will explain this in more detail in the following section.

What are the potential risks and how can you mitigate them?

Apart from carrying out necessary due diligence processes, companies should also watch out for latent risks that might be brought about following the implementation of ECL. It is worth flagging up the potential conflicts between ECL and the export control laws or anti-boycott regulations of the relevant jurisdictions that may be applicable to the transaction and the parties concerned.

Some countries and regions’ export control laws have long-arm jurisdiction and can apply extraterritorially to persons abroad. Complying with ECL could lead to a potential breach of laws from other jurisdictions and vice versa. For instance, complying with ECL may result in the breach of US Anti-Boycott Regulations for certain companies. For those US-funded companies in China and Chinese companies with a substantial commercial presence in the US, they are likely to face a dilemma: complying with ECL may cause them to be sanctioned by the US authorities; while complying with US Anti-Boycott Regulations may lead them to be sanctioned by Chinese authorities. If that is the case, it will be essential to find a way out to prevent those entities from being sanctioned by other jurisdictions for complying with the requirements under ECL.

Complying with ECL could lead to a potential breach of laws from other jurisdictions and vice versa.

Moreover, companies or financial institutions that provide funds to those entities being regulated by ECL should also be wary of the potential risks. If the debtors are sanctioned by ECL, the creditors will face the risk that the creditworthiness and repayment ability of the debtors may be adversely affected by such sanction. To mitigate the risks, our general suggestions are outlined below:

Compliance clause

For those companies whose business could be significantly influenced by ECL, it is necessary to revisit and make necessary amendments to the compliance clauses in their existing transactional documents. For certain overseas companies, their compliance clauses are usually tailored to fit for specific compliance requirements of the jurisdiction where they or their parent companies are located.

Since the compliance requirements may differ from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, the compliance clauses designed for one jurisdiction may not be sufficient to fulfil the requirements set out by ECL. As such, companies should consider drafting tailor-made compliance clauses to fulfil the requirements under all applicable laws for a specific transaction and follow its internal risk assessment policies.

Representations and warranties clauses

To mitigate any deal-killing risks, one party should consider at an early stage requiring the counterparty to insert certain clauses to mitigate the risk – such as representations and warranties clauses, undertakings and covenants that are made by the restricted entity –stating that by carrying out the export or import transaction and entering into the transactional documents, it has not and will not violate any applicable export control regulations or sanction rules in all the relevant jurisdictions. Besides, the termination clause and force majeure clause should be carefully drafted to include situations where ECL is not complied with.

Sanction clause

For creditors of any restricted entities, such as banks, it is necessary to review the facility agreement to which those restricted entities are parties. The aim of the review is to ensure that sanction provisions incorporate requirements set out by ECL, and warranties clauses are put in place to guarantee compliance with ECL.

Exemptions for non-compliance with laws of certain jurisdictions

As mentioned above, companies could be prevented from implementing policies of other nations which run counter to the policy of their home country under any export control laws or anti-boycott laws with long-arm jurisdictions. Nevertheless, there are certain exemptions which may allow for non-compliance or conditional compliance with relevant jurisdictions’ boycott requirements.

We suggest companies seek legal advice from professional lawyers to review, amend and supplement relevant provisions in transactional documents and request their lawyers to issue legal opinion opining on regulatory compliance of the underlying transaction where necessary.

For more information about the ECL contact ZhongLun Law Offices