Tom Pattinson speaks to London-based town planner and social economist Dr Wei Yang about China’s urban planning and how a Victorian town planner of British home county towns might have a big impact in China

Wei Yang might speak softly but she talks boldly about what China could learn from Britain. We meet in a majestic hotel in her adopted home of London to compare notes on the last three decades of urban change in China, change that has been orchestrated from her birth town of Beijing.

China has become a destination for architects, town planners and social economists interested in managing a country of nearly a billion and half people, and who ask how new models can be implemented on a grand scale. With over 58 percent of the population living in urban areas (up from less than 18 percent in 1978), keeping cities moving, the air clean and their inhabitants happy is a challenge that Yang relishes.

The Megacity

Yang talks about the recent history of Chinese urbanisation. The megacities of Beijing and Shanghai were attractive 30 years ago, she explains; prices were low, work was plentiful and space was abundant. But today, these polluted cities are overpopulated, jammed with traffic and have major constraints on health care and education infrastructure.

“The government thinks these cities are now mature enough and should export economic benefit to surrounding cities,” she says. Yang is talking about the Chinese government’s current policy of promoting regional clusters such as Jingjinji, the Yangtze River Delta and the Greater Bay Area – as well as clusters around Chengdu and Xian in the future. The aim is also to take the stress off the services in the major cities. Rapidly developing strategic transportation – high-speed rail and inner-city transportation links – makes this feasible, she explains.

There are positives and negatives to such megacity clusters though. The clusters will help to regenerate and encourage social-economic development of the surrounding areas but, she argues, this is already happening naturally to a degree. “In places like Changzhou and Huzhou near Shanghai, they are already gaining benefits from the economic growth of the surrounding megacities.”

The main concern for Yang is that these areas could become overdeveloped, which would be a waste of land, money and energy. “It will help for people to have more choices but if it is over-scaled, the development will be very dispersed. Efficient land use with proper transport connections, proper jobs and a proper housing mix are what is important,” she says.

In recent years many areas in China have suffered such overdevelopment. This has led to the creation of ‘ghost cities’ – neighbourhoods, or entire districts and towns, packed with empty sky rises and devoid of residents. This is in part due to China’s development model, where local governments rely on housing estate developers to buy land from the government, which then gives the government the funds needed to provide services. But many towns have ended up standing empty as speculators and investors buy up property and keep it empty.

“In the UK, older properties are usually worth more than new ones but in China older properties are regarded as ‘second hand’ if someone has lived in them before,” she explains. Therefore, new builds will sit empty and bare and remain ‘new’ so as not to devalue them.

As there is nothing akin to council tax in China, it doesn’t cost a landlord anything to keep a property – empty or not. “At the moment in China there is a big debate as to whether local councils should introduce council tax,” says Yang. “In the UK more than 40 percent of local services are paid for with council tax – policing, healthcare, education. It is a good way to get income for the local authorities.”

Due to the fast urbanisation process in China, land sale has become one of the main income sources for local governments. This has the potential to become a problem when all the land is sold and further investment in the area is needed. Unlike in the UK, “building roads, rails, facilities, schools and services and green areas and public spaces are the responsibility of the state not the developer,” says Yang.

All land in urban areas in China is owned by the state with residential property leases given for just 70 years. Some buildings are already 20 or 30 years into their lease and there is no clear structure of what happens when the lease expires. It could be extended or renewed, or it could be given to the leaseholder but it also could be taken back by the state and resold. Whatever might happen at the end of the lease, for its duration, the state continues to incur costs as it is responsible for all services yet does not absorb any further revenue as the lease was sold upfront.

The liveable city

Today, says Yang, the new cities, megacities and city clusters are being future-proofed as best as possible. “They try to build them as well as they can. The Chinese government is very keen to use best practise but sometimes there is a mismatch,” she says. Competing departments have different priorities. The transport department might think that more roads and high-speed railways are a priority, whilst the economists would like to see more business parks and industrial estates being built.

This can lead to segmented and fragmented cities, says Yang. Therefore, the importance of town planning is essential to ensure that the public transport system is well connected so people don’t have to rely on cars. That there are not just economic programmes introduced but that cities are also liveable.

Garden Cities were taught briefly in our Chinese planning text books but only as utopian societies; however, the more I studied the more I realised that some were thriving and very successful

“We need to change the fundamental mindset,” she says. “For a lot of local authorities, they still think the priorities are economic development, when a new industrial estate doesn’t necessarily help. What is needed is a liveable city. What is actually important is this human factor and how to properly consider it.”

Yang says that the speed of growth has slowed as the authorities ensure development is more considered. “Ten or twenty years ago the rate of growth was very, very fast. The rate is now being controlled. It is now almost impossible to develop agricultural land for example.” Only 12.6 percent of China’s land is arable, and food security is a real issue in China – therefore the authorities are doing all they can to reduce desertification and urbanisation; getting permission to use valuable agricultural land is now near impossible.

Instead of using greenfield sites, China focus is shifting towards regeneration. “The government is trying to do more work to recapture smaller towns and villages and that is a major policy shift.

“People are realising that all these big cities look the same and start to lose their cultural heritage. These rural communities and towns are the foundation of our cultural ecosystem and the government is realising that losing them is a problem.”

British style planning regulations and permissions are one method China may adopt in order to avoid creating more cookie-cutter towns that are often devoid of character and local culture.

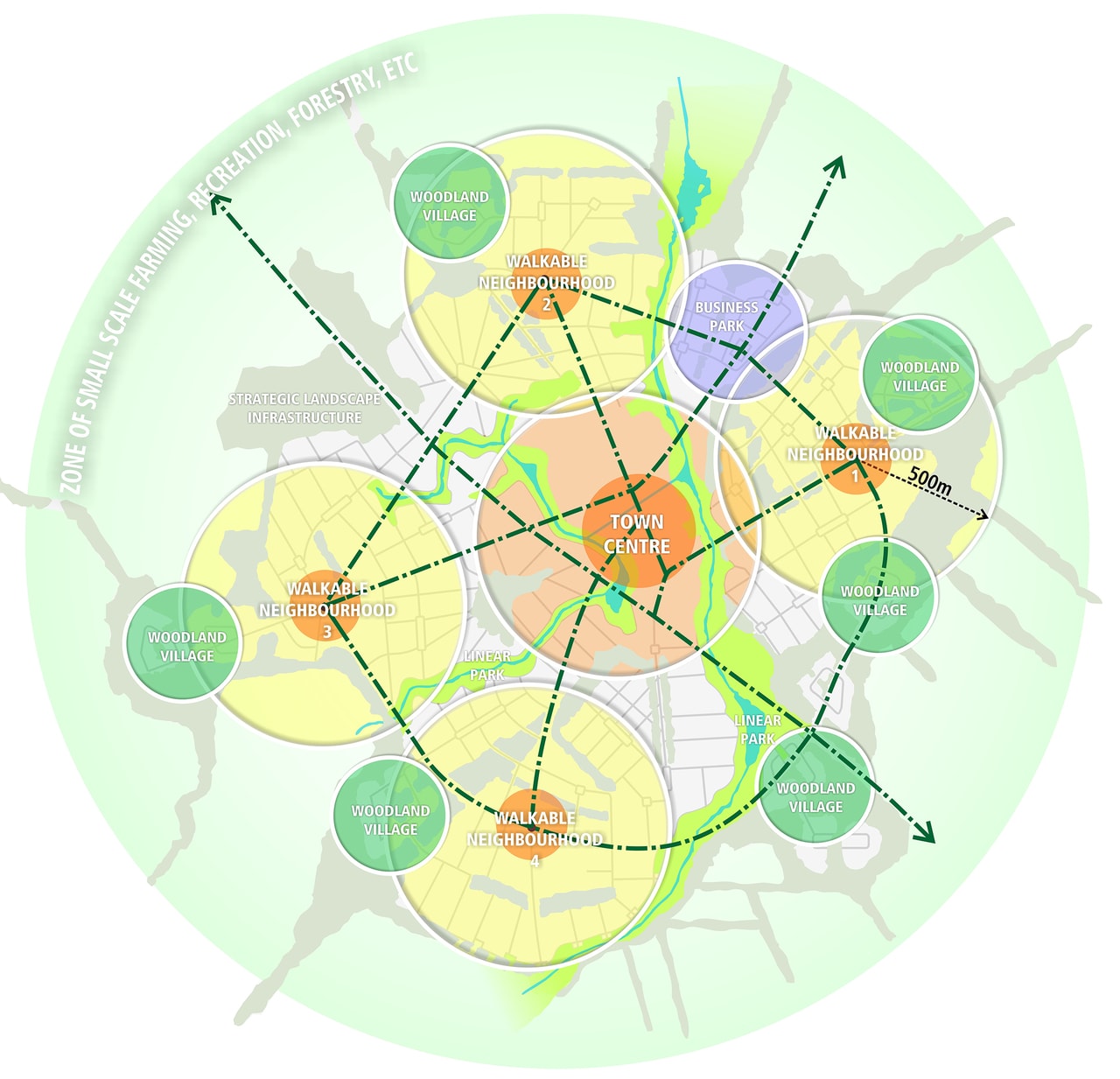

Wei Yang Garden City Model – Wolfson Economics Prize 2014

The Garden city

Another British model that Yang is excited to bring to China is a little-known Victorian socio-economic model that gave birth to some of England’s suburban home counties towns: Garden Cities.

“People think about town planning as design but the more I learnt about town planning through real projects, the more I realise design itself can’t resolve everything. You need to think about the socio-economic model,” says Yang, “how to reform land ownership and how to develop the land to ensure the value increases through the development process. It’s about how to manage the land, not just about how to design it.”

“Garden Cities were taught briefly in our Chinese planning textbooks but only as utopian societies; however, the more I studied the more I realised that some, like Welwyn Garden City and Letchworth Garden City, were thriving and very successful,” she says.

The Garden City model sees the community establishing a residents’ trust that manages the land, which is then rented for industrial, commercial and agricultural purposes to subsidise housing and improve services in the area.

“It relates to big questions about society. Who should own the land? Who should develop the land? And who should get the benefit from it? If that model is not resolved, then we have a lot of problems like we have now, such as affordability, segregated communities, disconnected transportation and jobs a significant distance from where people live.”

“Through my previous projects I realised the reasons some project couldn’t really deliver the vision we had was because these things were not being considered all together. So, I started to question the fundamental principles of town planning.”

We think it will be very beneficial to have a community trust that brings together stakeholder who can share a vision

In 2013, a British governmental push for new garden cities saw Wei Yang & Partners make the final five in the 2014 Wolfson’s Economic Prize and the company rapidly became one of most established companies in the field. Following this, in the summer of 2017, they completed a project in Jinjiang City in Fujian that adhered to the Garden City principles. It was recently commended by the Royal Town Planning Institute International Award for Planning Excellence.

Jinjiang is wealthy, thanks to its strategic location on the coast near Xiamen and opposite Taiwan, and the wealthy diaspora who return to the region to trade and invest. It is also home to historical villages – one of which was selected as a pilot town as part of the central government’s promotion of the small town gentrification model.

A campus of Fujian University was opened and the town was named ‘Jinjiang Dreamtown for Talents’ in a bid to attract university students to stay longer and start their own business in the community. Many of the historical buildings that are derelict and empty have been earmarked for renovation to be used as incubator and start-up spaces, studios or workshops. The buildings are ready to be retro-fitted and locals are opening hostels and finding other opportunities.

“We are talking about how we can build infrastructure that supports the community, such as cycleways, tourist information centres and where the best places are for restaurants, cultural facilities and car parks. It’s a programme for syncing everything together.”

Jinjiang Dream Town – Regenration Plan of Tangdong Village

“The most important thing is our inspiration from the Garden City principles,” says Yang. “We think it will be very beneficial to have a Dream Town Communities Trust that brings together stakeholders from the campus, from the village, from the city and from overseas relatives. People can share a vision and by having exclusive development rights the trust can make money through development and then use this to contribute back to the welfare system, provide essential maintenance of the village and maintain the connection with the university.”

Currently, after a 70-year lease is sold to a developer all the money arrives at once but the government have continuing, and increasing, costs as more people move on to the land. Education, healthcare and transportation – all this is the responsibility of the government. “The developers don’t have any future responsibilities for looking after these people.” China needs to consider long term management responsibility, which has become a major burden for local authorities. “You need a mechanism that allows for sustainable income every year,” Yang says.

Yang clearly has a passion for preserving traditional culture by regenerating old towns, but it is her desire for a strong land reform policy that will help change the mind set of a nation. And it may well be a Victorian town planner has a lot more influence on the urban world a century on, than he did in his own lifetime.

For more information about China’s urban environment contact Xu Jiawei in Beijing on Jiawei.Xu@cbbc.org.cn