Earlier this month, China’s leadership published its proposal for the 14th Five Year Plan, which will serve as a blueprint and scorecard for economic policy in the coming 5 years. As expected, technological self-reliance and the new Dual Circulation Strategy are top of the agenda. Further opening up and the liberalisation of China’s service sector remain important goals. CBBC’s Torsten Weller gives his analysis

Unusually, the proposal does not include specific economic growth targets. However, it does provide more details about the Chinese leadership’s principal areas of concern over the economy’s future path.

The key takeaway: The proposal confirms our initial assessment that the government’s Dual Circulation Strategy – that is the strengthening of China’s own consumer market paired with the technological upgrading of its manufacturing sector – will be central to the 14th Five Year Plan (FYP).

Economic growth

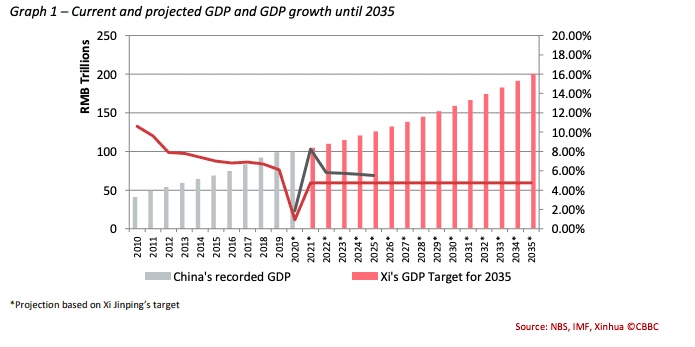

As mentioned above, the 14th FYP documents that have been published so far contain no specific economic growth targets. Nonetheless, in a commentary on the 5th Plenum’s decisions, Xi Jinping expressed confidence that China could double the size of its economy by 2035.

What does that aim imply for China’s future growth?

China’s GDP last year topped RMB 99 trillion (£11.4 trillion). The communiqué issued after the 5th Plenum noted that Chinese leaders expect the economy to pass the RMB 100 trillion threshold this year. Xi’s statement also links up to China’s previous objective of doubling the economy between 2010 and 2020, a goal which it will almost certainly achieve given that China’s GDP ten years ago was only RMB 40 trillion (£4.6 trillion).

UK goods exports will undoubtedly benefit from further economic growth and the increasing purchasing power of Chinese consumers

A further doubling of the economy’s size by 2035 implies China’s growth over the next decade-and-a-half will be lower than the average of 6.4% per annum over the last decade, at around 4.75% per annum. This is largely in line with recent projections by the IMF, which predicts an average annual growth of 6.2% between 2021 and 2025.

If this growth rate comes to pass it would mean China growing by the equivalent of Turkey’s current annual output each year out to 2035.

The domestic market and Dual Circulation Strategy

China’s leaders are hoping that growth over the next five years will largely stem from domestic consumption and high-quality service industries, in contrast to the last decade, when labour-intensive export industries and infrastructure investment were the economy’s biggest drivers.

In order to boost domestic spending, the Chinese government plans to implement its so-called Dual Circulation Strategy (DCS). The main idea behind this strategy is to strengthen China’s vast domestic market (‘domestic circulation’), while balancing its foreign trade (‘external circulation’).

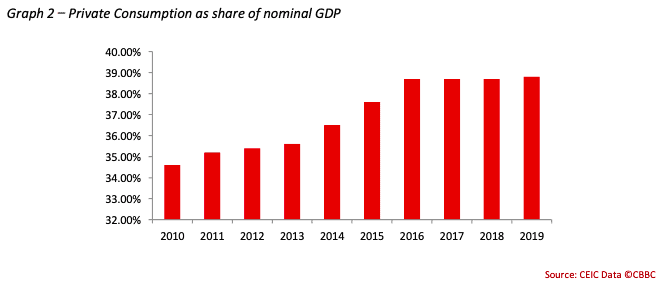

Key to this strategy will be a considerable increase in consumption as a share of China’s economy. Yet private consumption as a share of nominal GDP has plateaued over the last five years at around 39%, according to data from CEIC. While a slowing economy is partly to blame, increased living costs and soaring house prices have had a chilling effect on consumption.

Freeing up cash for greater household consumption will require painful and costly reforms to redistribute wealth – including a better welfare safety net and more efficient financial markets. More ambitious changes to China’s restrictive household registration system, which bans millions of rural citizens from accessing social services in cities, would also help.

The proposal does mention further supply-side measures which, inter alia, target the removal of domestic trade barriers and monopoly pricing powers for key commodities producers. Private businesses in China have repeatedly complained about the inflexible pricing policies of China’s raw materials producers and key infrastructure providers, many of which are state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

According to Craig Allen of the US-China Business Council, up to 45% of China’s economy remains closed to private and foreign competition, mostly in upstream business sectors – including telecommunications, media, electric power, oil and gas, coal, steel, aluminium, construction, engineering, aviation, railways and most of the insurance and banking sector.

Whether such reforms can and will be implemented remains to be seen. The Xi government’s current policies towards SOEs have focused on both consolidation and the greater participation of private capital. Monopoly break-ups have remained rare and currently appear to be aimed more at private tech firms like Alibaba rather than public enterprises.

Indigenous innovation

A more promising objective of the new FYP is the promotion of indigenous innovation. In a recently published speech, Xi Jinping cautioned that China “should not simply repeat the past model but should strive to comprehensively increase technological innovation and import substitution.” This, added Xi, “is to deepen the supply-side structural reform. The focus is also the key to achieving high-quality development.”

Key industries mentioned in the proposal are artificial intelligence, quantum computers, semiconductors, health and life sciences, neuroscience, biological engineering, aerospace technologies, and deep-sea exploration.

Although US sanctions against major Chinese tech companies have been frequently cited by Beijing officials as the rationale for trying to achieve greater autonomy in advanced hardware and software production, most of the target sectors have been a part of China’s drive to become a leader in next-generation technologies for some time. The Chinese government’s Made in China 2025 Strategy – which was modelled after the German ‘Industry 4.0’ scheme – already includes specific targets for most of these sectors.

China will need to buttress its internal development in areas such as technology and renewable energy with foreign capital and expertise

China’s push for a competitive domestic semiconductors industry – the sector at the heart of the current technological battle – also predates the current clash with the US. The Chinese government issued policies supporting the development of local chip manufacturers in both 2000 and 2011.

Industry analysts believe that China is capable of achieving a world-class level of technologies in these areas. For example, Matt Sheehan of the Paulson Institute and author of ‘The Transpacific Experiment’, a book on the collaboration between China and Silicon Valley, wrote in a recent forecast that by 2025, China will probably be on par with Silicon Valley in terms of dynamism, innovation, and competitiveness.

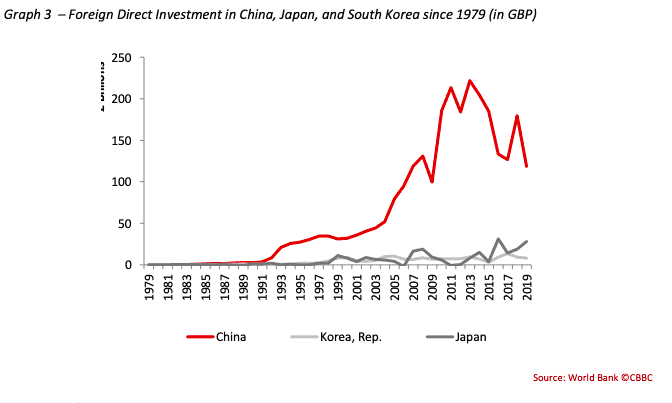

Yet achieving this goal will probably require more, not less international cooperation. Even by the standards of East Asian developmental state intervention, China’s policy approach to industrial modernisation has been heavily reliant on foreign investment and expertise. Over the last 40 years, China has attracted nearly seven times as much foreign investment as Japan and South Korea combined.

That China’s semiconductor industry will struggle to take off without foreign capital became clear in July, when Wuhan Hongxin Semiconductor Manufacturing announced that it had been forced to halt its production of advanced 14nm and 7nm semiconductors due to a funding shortfall of £14 billion.

Foreign trade

Foreign trade and openness to foreign business will be crucial for China to achieve its goals of greater technological innovation and higher levels of consumption. The proposal for the 14th FYP reflects this and calls for ‘comprehensively improving the level of opening to the outside world and the promotion of trade and investment liberalisation and facilitation’.

While many of the proposed measures – such as better intellectual property rights and legal protection for foreign businesses – are in line with China’s existing policies to improve the business environment, plans for the further opening up of the service sector and the proposed drafting of a ‘negative list for services’ mark the biggest novelty in the new FYP.

After Hainan province announced its plan to establish such a list for its planned Free Trade Port in June, Xi Jinping declared in September that the list would, in fact, be applied nationwide and that the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region (usually known as the ‘Jing-Jin-Ji’ area) would assume a pioneering role in this reform.

While there are few concrete details yet about the exact content of the list, the liberalisation of China’s financial and insurance sectors offers a useful template for future reforms. Reforms to allow foreign financial institutions to fully own subsidiaries in China’s securities, futures, bond, and insurance markets have attracted nearly £58 billion in foreign investment in the first half of 2020 – almost £20 billion more than the US in the same period.

Recent reforms in Shenzhen to harmonise standards for professional service providers in the Greater Bay Area offer another example. The new Pilot Reforms Plan, which was unveiled at the beginning of October, recognises foreign qualifications in certain sectors, including accounting and healthcare, and allows foreign professionals to work in China without having to obtain a local equivalent certificate.

Similar reforms are expected to be rolled out across China in the coming months and years with the healthcare, educational sector, and business services being the most frequently mentioned by Chinese policymakers.

CBBC View

Several commentators have recently warned that China’s economy is taking an inward turn. However, the logic of China’s economic plans instead suggest that its economy will continue to offer growth opportunities for UK businesses in the coming five to fifteen years.

China will need to buttress its internal development in areas such as technology and renewable energy with foreign capital and expertise, for example. Moreover, the long-hoped-for shift to greater reliance on domestic consumption should offer huge opportunities for UK businesses in sectors from retail to food & drink. China’s growing demand for professional and financial services could open up new entry channels for UK services providers and augur a considerable increase in British services exports to China.

Already last year, the UK exported £5.5 billion worth of services to China, a jump of nearly 19% year-on-year and a 150% increase compared to 2010. We expect further growth in this area in the coming years.

UK goods exports will also undoubtedly benefit from further economic growth and the increasing purchasing power of Chinese consumers. During the pandemic, China has remained one of the few growth markets for British exporters. Recent Chinese customs data shows that its imports of UK consumer goods – which excludes crude oil and non-monetary gold – had grown 1.9% in the first nine months of 2020 compared to the same period last year, outperforming other European economies, which have seen their imports shrink by nearly 8%. British businesses are well placed to benefit further from rising Chinese household demand, once China’s domestic reforms start to kick in.

Overall, the guidelines of the 14th Five-Year-Plan promise a continuation of the major reform trajectory of the last ten years, which have seen a tripling of UK goods and service exports to China.